PEDIATRIC SURGERY UPDATE ©

VOLUME 41, 2013

PSU Volume 41 No 01 JULY 2013

Acquired Jeune's Syndrome

Jeune's syndrome, also known as

asphyxiating thoracic dysplasia, is a type of thoracic dystrophy with

severe narrow thorax leading to respiratory distress and even death in

its more severe form. Jeune's syndrome either is congenital (autosomal

recessive) or acquired. The acquired form of Jeune's syndrome was

described in 1996 in children who had undergone repair of pectus

excavatum chest wall deformity utilizing the traditional open (Ravitch)

approach with subperichondrial resection of deformed cartilages and

transverse osteotomy performed too early an age (less than four years

of age). Permanent impairment of normal chest wall growth and

subsequent restriction of lung expansion during respiration creates

this type of acquired form of the disease. Years later after the

primary procedure for pectus these children developed progressive

dyspnea with mild exertion associated to restrictive pulmonary function

tests with forced vital capacity (FVC) of 30-50% and forced expiratory

volume in one second (FEV1) of 30-60% of predicted values. This

acquired restrictive thoracic dystrophy is due to an aggressive

resection of the involved deformed cartilages including the second

costal cartilage. This complication does not occur using the actual

minimally invasive repair of pectus excavatum (Nuss technique).

Diagnosis is done using pulmonary function tests and three-dimensional

CT reconstruction of the chest. Management of acquired Jeune's syndrome

includes displacing the sternum forward with a splint or median

sternotomy with interposition of autologous rib grafts to increase the

chest wall diameter (Weber technique). Substantial improvement in PFT

and clinical symptoms can be achieved with the sternal split technique

though long-term evaluation is awaiting results.

References:

1- de Vries J, Yntema JL, van Die CE, Crama N, Cornelissen EA, Hamel

BC: Jeune syndrome: description of 13 cases and a proposal for

follow-up protocol. Eur J Pediatr. 169(1):77-88, 20102- Weber TR,

Kurkchubasche AG: Operative management of asphyxiating thoracic

dystrophy after pectus repair. J Pediatr Surg. 33(2):262-5, 19983-

Fokin AA, Robicsek F: Acquired deformities of the anterior chest wall.

Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 54(1):57-61, 20064- Weber TR: Further

experience with the operative management of asphyxiating thoracic

dystrophy after pectus repair. J Pediatr Surg. 40(1):170-3, 20055-

Phillips JD, van Aalst JA: Jeune's syndrome (asphyxiating thoracic

dystrophy): congenital and acquired. Semin Pediatr Surg. 17(3):167-72,

2008 6- Lopushinsky SR, Fecteau AH: Pectus deformities: a review of

open surgery in the modern era. Semin Pediatr Surg. 17(3):201-8, 2008

Metal Allergy

Jewelry, dental and surgical implants

from craniofacial, orthopedic, neurosurgical and pediatric surgery

physicians can lead to metal allergy in children. As many as 13% of

patients are sensitive to nickel, cobalt or chromium. Metal allergy

from nickel is the most common contact allergy in the United States and

Europe. The classical symptom of dermatitis caused by nickel is a rash

in the earlobes, periumbilical region or wrist resulting from contact

with costume jewelry, buttons and zipper. Metal allergy is a typical

delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction caused by T-lymphocytes

reaction. CD8 and CD4 cells cause cytotoxic and inflammatory response

to the metal. Children with metal allergy usually elicit a past history

of atopy including allergic rhinitis, asthma, eczema and urticarial

rash. Metal allergies are frequently misdiagnosed as surgical

infections. Symptoms of inflammation such as pain, warmth, erythema and

swelling can be seen over the implant, including pericarditis and

pleural effusion in those in a thoracic position. As a screening

measure to determine if a child can or might develop metal allergy to

an implant the following should be evaluated: 1- history of allergy to

jewelry, orthodontic braces, metal buttons on clothing and food. 2-

History of previous atopy and eczema. If any of the above indications

are found, a dermal patch test should be performed. This patch test

contains 23 allergens and allergen mixes that cause up to 80% of

allergic contact dermatitis cases. Should the child be found to have

metal allergy implants of titanium should be considered, since titanium

does not produce allergic reactions but are more

expensive.

References:

1- Mortz CG, Lauritsen JM, Bindslev-Jensen C, Andersen KE:

Nickel sensitization in adolescents and association with ear piercing,

use of dental braces and hand eczema. The Odense Adolescence Cohort

Study on Atopic Diseases and Dermatitis (TOACS). Acta Derm Venereol.

82(5):359-64, 2002

2- Dotterud LK, Falk ES: Metal allergy in north Norwegian

schoolchildren and its relationship with ear piercing and atopy.

Contact Dermatitis. 31(5):308-13, 1994

3- Kalimo K, Mattila L, Kautiainen H: Nickel allergy and orthodontic treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 18(5):543-5, 2004

4- Katting B, Brehler R, Traupe H: Allergic contact dermatitis

in children: strategies of prevention and risk management. Eur J

Dermatol. 14(2):80-5, 2004

5- Rushing GD, Goretsky MJ, Gustin T, Morales M, Kelly RE Jr,

Nuss D: When it is not an infection: metal allergy after the Nuss

procedure for repair of pectus excavatum. J Pediatr Surg. 42(1):93-7,

2007

6- Thyssen JP, Jakobsen SS, Engkilde K, Johansen JD,

SA¸balle K, Menna T: The association between metal allergy, total

hip arthroplasty, and revision. Acta Orthop. 80(6):646-52, 2009

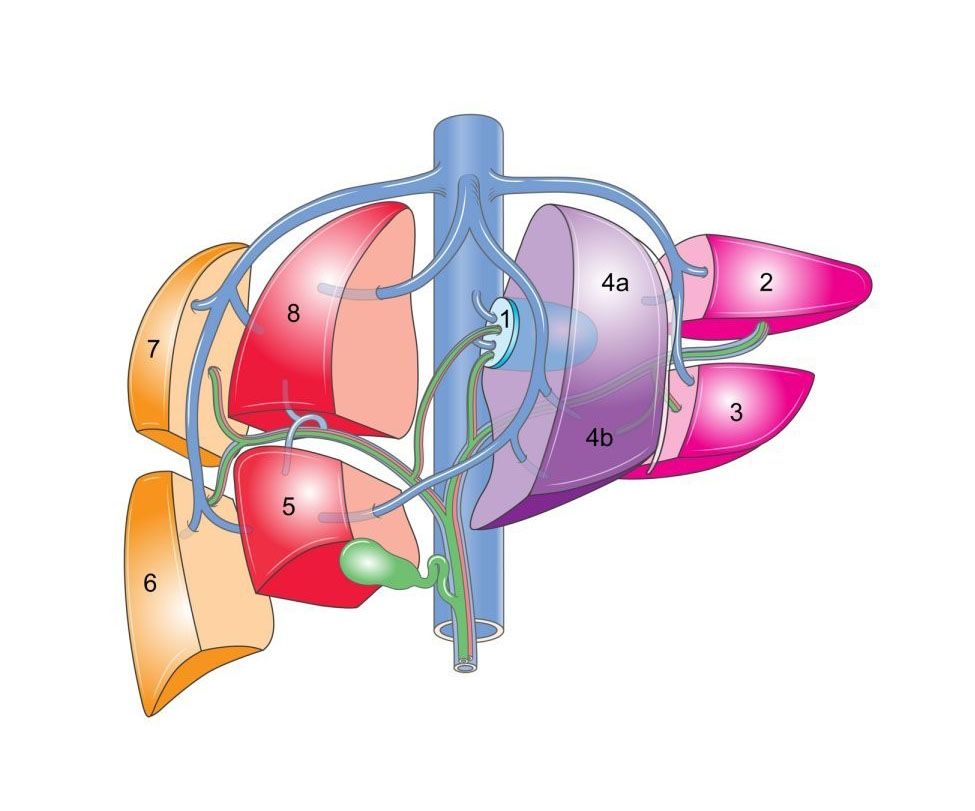

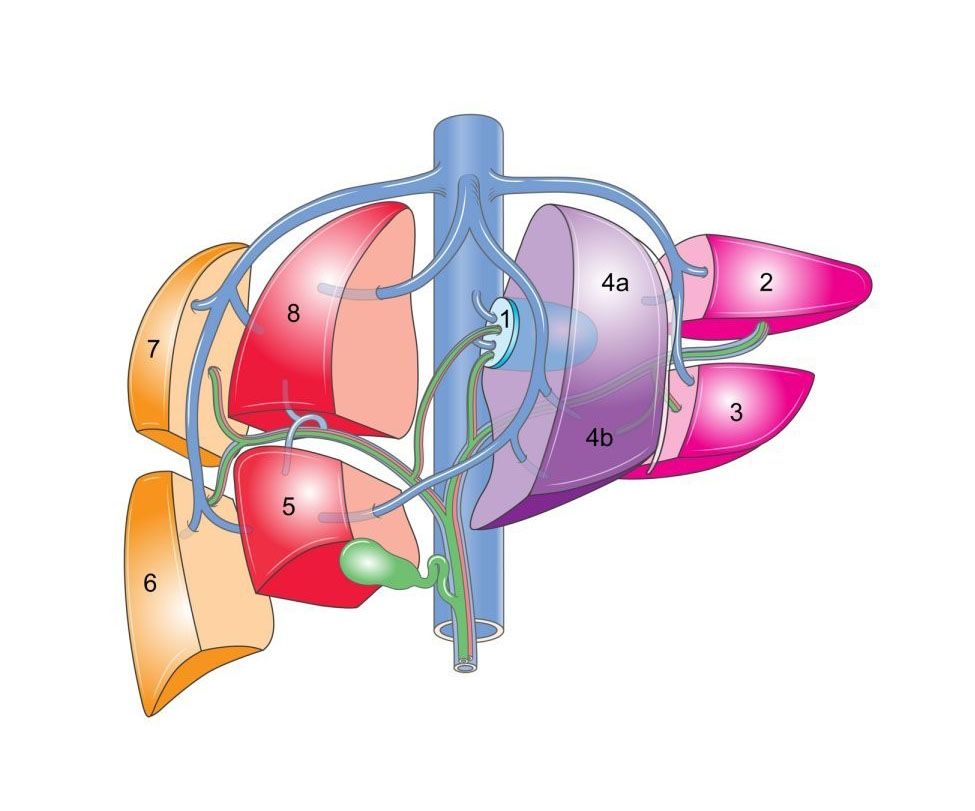

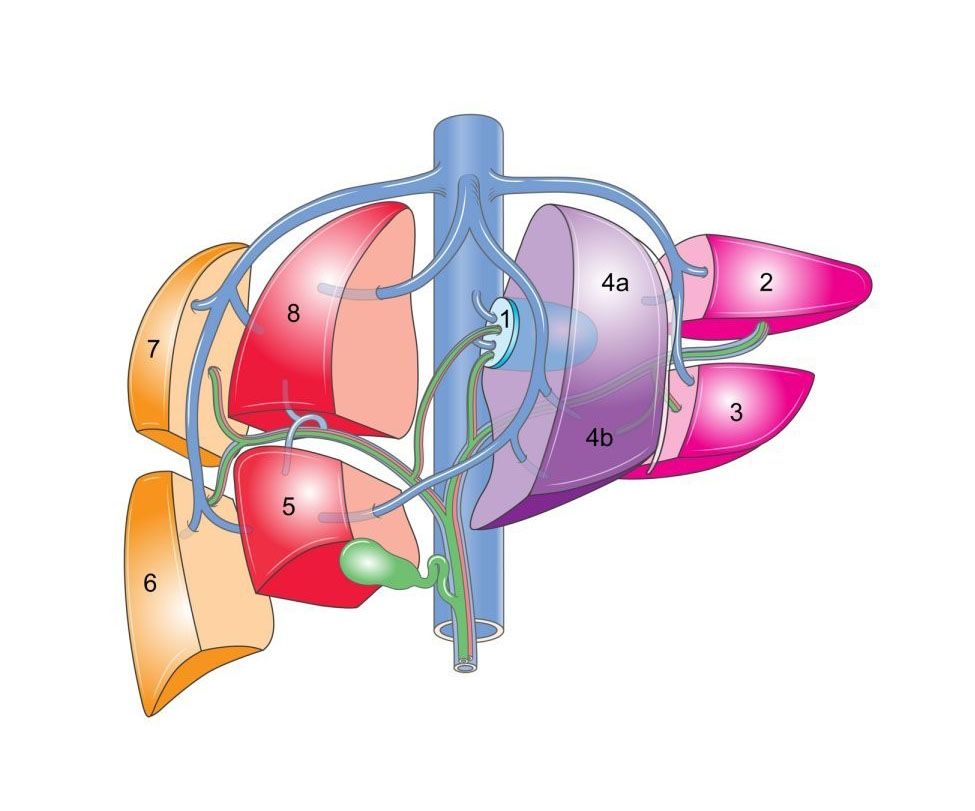

PRETEXT

The PRETEXT (PRE Treatment EXTent of

disease) system was designed by the International Childhood Liver Tumor

Strategy Group (SIOPEL) for staging and risk stratification of liver

tumors, namely hepatoblastoma, hepatocellular carcinoma and epithelioid

hemangioendothelioma. PRETEXT describes tumor extent before any therapy

allowing different groups to have a more effective comparison in future

studies. PRETEXT staging is based on Couinaud's liver segmentation

grouping the liver into four sections: segment 2 and 3 (left lateral

section), segment 4a and 4b (left medial section), segments 5 and 8

(right anterior section) and segments 6 and 7 (right posterior

section). The PRETEXT number is derived by subtracting the highest

number of contiguous liver sections that are not involved by tumor from

four. PRETEXT also utilizes other criteria such as involvement of the

caudate lobe (designated C), involvement of the inferior vena cava or

hepatic veins (V), involvement of the portal veins (P), extrahepatic

abdominal disease (E) and distant metastasis (M). Other high risk

criteria include tumor rupture or intraperitoneal hemorrhage at

diagnosis (H1) and alpha fetoprotein levels below 100 ug/L. In PRETEXT

I one section is involved and three are free. This group includes only

a small portion of all cases. In PRETEXT II one or two sections re

involved, but two adjoining sections are free. They are limited to the

right lobe or left lobe of the liver. In PRETEXT III two or three

sections are involved and no two adjoining sections are free. The

unifocal tumors in this category spare only the left lateral or right

posterior section. This group is relatively common. In PRETEXT IV all

four sections are involved. Involvement of the caudate lobe is a

potential predictor of a poor outcome. Extrahepatic disease refers to

diaphragm involvement, peritoneal seeding, ascites and abdominal lymph

node metastasis. Distant metastasis is manly to the

lung.

References:

1- Brown J, Perilongo G, Shafford E, Keeling J, Pritchard J,

Brock P, Dicks-Mireaux C, Phillips A, Vos A, Plaschkes J: Pretreatment

prognostic factors for children with hepatoblastoma-- results from

the International Society of Paediatric Oncology (SIOP) study SIOPEL 1. Eur J Cancer. 36(11):1418-25, 2000

2- Perilongo G, Shafford E, Plaschkes J; Liver Tumour Study

Group of the International Society of Paediatric Oncology: SIOPEL

trials using preoperative chemotherapy in hepatoblastoma. Lancet Oncol.

1:94-100, 2000

3- Roebuck DJ, Aronson D, Clapuyt P, Czauderna P, de Ville de

Goyet J, Gauthier F, Mackinlay G, Maibach R, McHugh K, Olsen OE, Otte

JB, Pariente D, Plaschkes J, Childs M, Perilongo G; International

Childrhood Liver Tumor Strategy Group: 2005 PRETEXT: a revised staging

system for primary malignant liver tumours of childhood developed by

the SIOPEL group. Pediatr Radiol. 37(2):123-32, 2007

4- Roebuck DJ: Assessment of malignant liver tumors in children. Cancer Imaging. 9: S98-S103, 2009

5- Meyers RL, Czauderna P, Otte JB: Surgical treatment of hepatoblastoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 59(5):800-8, 2012

6- Tajiri T, Kimura O, Fumino S, Furukawa T, Iehara T, Souzaki

R, Kinoshita Y, Koga Y, Suminoe A, Hara T, Kohashi K, Oda Y,

Hishiki T, Hosoi H, Hiyama E, Taguchi T: Surgical strategies for

unresectable hepatoblastomas. J Pediatr Surg. 47(12):2194-8, 2012

PSU Volume 41 No 02 AUGUST 2013

Duhamel Procedure

In 1956 Bernard Duhamel first

described a rectorectal pull-through procedure. Since then, the Duhamel

is a long standing pull-through procedure performed for the management

of Hirschsprung's disease (HD). In short, the procedure entails pulling

the proximal normal ganglionic bowel posterior to the aganglionic

rectum through the presacral space into the anus. A common lumen is

created with mechanical devices between the ganglionic and aganglionic

rectal bowel. The surgical approach to HD has changed from building an

initial temporary colostomy using a two or even three stage procedures,

to a one-stage surgical procedure in the neonatal period. As with any

other kind of surgical procedure for Hirschsprung's disease the child

can develop postoperative constipation, soiling or incontinence.

Constipation and soiling after the Duhamel procedure often are

associated with an anterior rectal pouch caused by a colorectal spur.

Constipation also may result from outlet obstruction caused by residual

spasticity of the internal sphincter or too long rectal aganglionic

bowel. Extended resection of the aganglionic rectum reduces the

incidence of fecalomas formation. Suboptimal outcome after operation

for Hirschsprung's' disease includes associated neuronal intestinal

dysplasia, total colonic involvement, significant neurological

impairment and history of enterocolitis all of which may result in

abnormal colonic motility in the remaining ganglionic bowel. Chronic

bleeding after Duhamel is caused by an incomplete section of the septum

between rectum and pull-through segment leaving the feeding artery on

the tip of the side-to-side anastomosis. After rectosigmoidectomy

alteration in bladder function such as increase bladder capacity and

urinary residual has been described. Open and laparoscopic Duhamel

procedure has similar outcomes.

References:

1- Baillie CT, Kenny SE, Rintala RJ, Booth JM, Lloyd DA: Long-term

outcome and colonic motility after the Duhamel procedure for

Hirschsprung's disease.J Pediatr Surg. 34(2):325-9, 1999

2- van der Zee DC, Bax KN: One-stage Duhamel-Martin procedure for

Hirschsprung's disease: a 5-year follow-up study. J Pediatr Surg.

35(10):1434-6, 2000

3- Mattioli G, Castagnetti M, Martucciello G, Jasonni V: Results of a

mechanical Duhamel pull-through for the treatment of

Hirschsprung's disease and intestinal neuronal dysplasia. J

Pediatr Surg. 39(9):1349-55, 2004

4- Chiengkriwate P, Patrapinyokul S, Sangkhathat S, Chowchuvech V:

Primary pull-through with modified Duhamel technique: 1 institution's

experience. J Pediatr Surg. 42(6):1075-80, 2007

5- Marquez TT, Acton RD, Hess DJ, Duval S, Saltzman DA: Comprehensive

review of procedures for total colonic aganglionosis. J Pediatr Surg.

44(1):257-65, 2009

6- Nah SA, de Coppi P, Kiely EM, Curry JI, Drake DP, Cross K, Spitz L,

Eaton S, Pierro A: Duhamel pull-through for Hirschsprung disease: a

comparison of open and laparoscopic techniques. J Pediatr Surg.

47(2):308-12, 2012

Prevention of NEC

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is the

most common surgical emergency in the neonatal intensive care unit

(NICU) associated with a significant morbidity and mortality. Due to

advances in neonatal care survival among premature and low birth weight

infants has improved though the mortality due to NEC has increased.

Prevention of NEC should be of upmost importance in most NICU. One of

the most important preventive measures in the development of NEC is

feeding infants at risk with breast milk as opposed to formula milk. If

fortification of breast milk is necessary to achieve adequate growth,

then a fortifier based on human milk lowers the incidence of NEC.

Another factor associated with lowering the incidence of NEC is whether

to use early or delayed enteral feedings. Current metaanalysis does not

support the use of a delayed introduction or slower rate of enteral

feeds to prevent NEC. They slower the weight gain and take longer time

to full feeding. Adverse effect of immunoglobulin administration or

prophylactic enteral antibiotics precluded their use as preventive

measure. Prophylactic antibiotics increase the colonization of

resistant bacteria. The other measure with strong evidence to use for

NEC prevention is the administration of probiotics and modulation of

feeding regimens in infants at high risk. Studies investigating

specific components of breast milk and probiotics responsible for these

protective effects have identified several molecules with therapeutic

potential such as erythropoietin, glutamine, and epidermal growth

factor all of which strengthen the gut barrier. Probiotics reduce

intestinal permeability, promote peristalsis, increase mucin secretion,

activate anti-inflammatory TLR9, downregulate proinflammatory cytokines

and upregulated antiinflammatory mediators.

References:

1- Morgan JA, Young L, McGuire W: Pathogenesis and prevention of

necrotizing enterocolitis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 24(3):183-9, 2011

2- Berman L, Moss RL: Necrotizing enterocolitis: an update. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 16(3):145-50, 2011

3- Ganguli K, Meng D, Rautava S, Lu L, Walker WA, Nanthakumar N:

Probiotics prevent necrotizing enterocolitis by modulating enterocyte

genes that regulate innate immune-mediated inflammation. Am J

Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 304(2):G132-41, 2013

4- Downard CD, Renaud E, St Peter SD, Abdullah F, Islam S, Saito JM,

Blakely ML, Huang EY, Arca MJ, Cassidy L, Aspelund G; 2012 American

Pediatric Surgical Association Outcomes Clinical Trials Committee.

Treatment of necrotizing enterocolitis: an American Pediatric Surgical

Association Outcomes and Clinical Trials Committee systematic review. J

Pediatr Surg. 47(11):2111-22, 2012

5- Bernardo WM, Aires FT, Carneiro RM, Sá FP, Rullo VE,

Burns DA: Effectiveness of probiotics in the prophylaxis of necrotizing

enterocolitis in preterm neonates: a systematic review and

meta-analysis. J Pediatr (Rio J). 89(1):18-24, 2013

6- Raval MV, Hall NJ, Pierro A, Moss RL: Evidence-based prevention and

surgical treatment of necrotizing enterocolitis-a review of randomized

controlled trials. Semin Pediatr Surg. 22(2):117-21, 2013

Music-Induced Stress Reduction

Music intervention has been found to

reduce procedure related anxiety for patients in the pre- and

intraoperative setting. Studies have shown that music reduced

self-reported stress levels and improve perceptions of patient-oriented

service in visitors to the surgery/intensive care unit waiting room.

Adults who listened to music while waiting with their children in the

pediatric emergency department, reported lower anxiety level than those

who did not listen to music. The level of formal education is inversely

correlated to degree of music-induced anxiety reduction. Music improved

the work environment for hospital staff and facilitated their

interactions with friends and family of patients. Allowing patients

control over music selection and providing uninterrupted time for music

listening gives the patients an enhanced sense of control in an

environment that often controls them. Music alone and music assisted

relaxation techniques significantly decreased arousal due to stress.

Further analysis revealed that the amount of stress reduction was

significantly different when considering age, type of stress, music

assisted relaxation technique, musical preference, previous music

experience, and type of intervention. Music specifically induces an

emotional response similar to a pleasant experience or happiness. Music

in the operating room has immeasurable effects. It can prevent

distraction, minimize annoyance, reduce stress, reduce the demands for

analgesic and anesthetics, and diminish the anxiety of patients, staff

and users.

References:

1- Pelletier CL: The effect of music on decreasing arousal due to

stress: a meta-analysis. J Music Ther. 41(3):192-214, 2004

2- Suda M, Morimoto K, Obata A, Koizumi H, Maki A: Emotional responses

to music: towards scientific perspectives on music therapy.

Neuroreport. 19(1):75-8, 2008

3- Makama JG, Ameh EA, Eguma SA: Music in the operating theatre:

opinions of staff and patients of a Nigerian teaching hospital. Afr

Health Sci. 10(4):386-9, 2010

4- Moris DN, Linos D: Music meets surgery: two sides to the art of "healing". Surg Endosc. 27(3):719-23, 2013

5- Tilt AC, Werner PD, Brown DF, Alam HB, Warshaw AL, Parry BA, Jazbar

B, Booker A, Stangenberg L, Fricchione GL, Benson H, Lillemoe KD,

Conrad C: Low degree of formal education and musical experience predict

degree of music-induced stress reduction in relatives and friends of

patients: a single-center, randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg.

257(5):834-8, 2013

6- Beaulieu-Boire G, Bourque S, Chagnon F, Chouinard L, Gallo-Payet N,

Lesur O: Music and biological stress dampening in

mechanically-ventilated patients at the intensive care unit

ward-a prospective interventional randomized crossover trial. J Crit

Care. Mar 14, 2013

PSU Volume 41 No 03 SEPTEMBER 2013

Octreotide

Octreotide is a synthetic peptide

analog of somatostatin with the same pharmacologic effect. Octreotide

has a longer half-life in circulation and higher potency than

somatostatin. Octreotide decreases the production of gastrointestinal

peptides, such as gastrin, secretin, gastric inhibitory peptide,

cholecystokinin, neurotensin, motilin, and pancreatic polypeptide.

Octreotide has several therapeutic uses in children. Octreotide

significantly reduced the amount of blood transfusions in children with

severe gastrointestinal bleeding and hemodynamic instability from acute

variceal hemorrhage. Octreotide successfully reduced bleeding in a

patient with typhlitis and cecal ulceration prior to surgery but failed

to control massive bleeding in children with a Meckel's diverticulum.

Octreotide inhibits pancreatic secretion and can be of help in

resolution of pancreatic pseudocysts allowing healing of pancreatic

duct with resolution of ascites. It can significantly reduce serum

lipase levels and reduce the clinical need for analgesics in acute

pancreatitis. Octreotide is effective in the management of chylothorax

by shortening the TPN duration, hospital stay and avoiding surgery

since it reduces thoracic duct lymph flow and absorption. Octreotide is

effective in reducing stool output in children with a variety of

disorders, including massive ileostomy losses, intestinal fistula,

congenital microvillus atrophy, idiopathic secretory diarrhea,

carcinoid tumor, cryptosporidium diarrhea and watery diarrhea

hypokalemia achlorhydria syndrome. Octreotide should be avoided in

patients with diagnosed or suspected congenital long Q–Tc

syndrome and cautiously used in conjunction with drugs that prolong

Q–T interval. Because of its inhibitory action on insulin,

octreotide has been associated with glucose intolerance and

hyperglycemia that may necessitate insulin therapy.

References:

1- Paget-Brown A, Kattwinkel J, Rodgers BM, Michalsky MP: The use of

octreotide to treat congenital chylothorax. J Pediatr Surg.

41(4):845-7, 2006

2- Al-Hussaini A, Butzner D: Therapeutic applications of octreotide in

pediatric patients. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 18(2):87-94, 2012

3- Nardone G, Rocco A, Balzano T, Budillon G: The efficacy of

octreotide therapy in chronic bleeding due to vascular abnormalities of

the gastrointestinal tract. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 13(11):1429-36, 1999

4- Heikenen JB, Pohl JF, Werlin SL, Bucuvalas JC: Octreotide in

pediatric patients. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 35(5):600-9, 2002

5- Sahin Y, Aydin D: Congenital chylothorax treated with octreotide. Indian J Pediatr. 72(10):885-8, 2005

6- Helin RD, Angeles ST, Bhat R: Octreotide therapy for chylothorax in

infants and children: A brief review. Pediatr Crit Care Med.

7(6):576-9, 2006

Peritoneovenous Shunt

Peritoneovenous shunt (PVS), also

known as Leveen or Denver shunt, is a shunt utilized to manage

medically intractable ascites in adults and children. These shunts

allow ascitic fluid to flow down a pressure gradient from the

peritoneal cavity to the venous circulation and have a valve mechanism

that prevents backflow of blood if the venous pressure rises above the

intraabdominal pressure. The advantage of the Denver shunt is that the

valve chamber lies in the subcutaneous tissue and therefore can be

manually compressed to relieve blockage and promote flow. The shunt can

also be flushed percutaneously if necessary. When peritoneal pressure

is 3 cm higher than CV pressure the valve opens. PVS can be placed

surgically, laparoscopically-assisted or percutaneously. Persistent

ascites is rare in children, carries a significant morbidity and is a

difficult management problem owing to the massive abdominal distension.

Etiology is often related to previous surgery, congenital malformation

of lymphatic channels, or idiopathic. Other causes include

inflammatory, neoplastic, traumatic, mechanical obstruction or

nonaccidental injury. Conservative and symptomatic management is

usually the mainstay of treatment while surgery is indicated when

conservative therapy fails. Certain complications have been described

in association with the procedure of placing the PVS. One of the major

concerns is diversion of large amounts of fluid into the central

circulation, potentially contributing to fluid overload. In

anticipation of this potential complication, diuretic therapy is

initiated that seemed to avoid this problem. Other reported

complications include shunt blockage and leaks, venous thrombosis,

disseminated intravascular coagulation, infection, and air embolus

during insertion. The PVS is an effective alternative in management for

intractable ascites in children.

References:

1- Blaylock RS, Emby D, Hopley M, Toogood JW: The peritoneo-saphenous

shunt for palliation of refractory ascites. S Afr J Surg. 39(3):83-5,

2001

2- Sooriakumaran P, McAndrew HF, Kiely EM, Spitz L, Pierro A:

Peritoneovenous shunting is an effective treatment for intractable

ascites. Postgrad Med J. 81(954):259-61, 2005

3- Matsufuji H, Nishio T, Hosoya R: Successful treatment for

intractable chylous ascites in a child using a peritoneovenous shunt.

Pediatr Surg Int. 22(5):471-3, 2006

4- Won JY, Choi SY, Ko HK, Kim SH, Lee KH, Lee JT, Lee do Y:

Percutaneous peritoneovenous shunt for treatment of refractory ascites.

J Vasc Interv Radiol. 19(12):1717-22, 2008

5- Rahman N, De Coppi P, Curry J, Drake D, Spitz L, Pierro A, Kiely E:

Persistent ascites can be effectively treated by peritoneovenous

shunts. J Pediatr Surg. 46(8): 315–319, 2011

6- Herman R, Kunisaki S, Molitor M, Gadepalli S, Hirschl R, Geiger J:

The use of peritoneal venous shunting for intractable neonatal ascites:

a short case series. J Pediatr Surg. 46(8):1651-4., 2011

Corpus Luteum Cyst

A corpus luteum cyst (CLC) is a

functional ovarian cyst very rarely found in adolescent girls. The cyst

develops when the corpus luteum fails to regress following the release

of the ovum. CLC may rupture about the time of menstruation and take up

to three months to disappear completely. This type of cyst occurs after

an egg has been released from a follicle. The follicle becomes a

secretory gland known as corpus luteum. Produces large quantity of

estrogen and progesterone in preparation for conception, but if

pregnancy does not occur it disappears. If it fills with fluid or blood

it will grow and create a cyst. The cyst might cause pain by way of

torsion, rupture or bleeding. Fertility drugs used to induce an

ovulation increase the risk of corpus luteum cyst development.

Symptomatic large ovarian cysts will need imaging, genetic marker

determination and surgery. Laparoscopy is becoming the favored approach

by most pediatric surgeons for the treatment of ovarian cysts with

benign imaging and labs characteristics. All surgical procedures for

ovarian cysts should spare functional ovary as much as is

technically possible. The management of symptomatic corpus luteum cysts

is ovarian cystectomy using the tissue sparing procedure of stripping

of the cyst. In cases of endometrioma cysts the amount of ovarian

tissue removed together with the cyst is significantly much greater

than with the nonendometriotic

cysts.

References:

1- Mayer JP, Bettolli M, Kolberg-Schwerdt A, Lempe M, Schlesinger F,

Hayek I, Schaarschmidt K: Laparoscopic approach to ovarian mass in

children and adolescents: already a standard in therapy. J Laparoendosc

Adv Surg Tech A. 19 Suppl 1:S111-5, 2009

2- Shapiro EY, Kaye JD, Palmer LS: Laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy in children. Urology. 73(3):526-8, 2009

3- Karpelowsky JS, Hei ER, Matthews K: Laparoscopic resection of benign

ovarian tumours in children with gonadal preservation. Pediatr Surg

Int. 25(3):251-4, 2009

4- Palmara V, Sturlese E, Romeo C, Arena F, De Dominici R, Villari D,

Impellizzeri P, Santoro G: Morphological study of the residual ovarian

tissue removed by laparoscopy or laparotomy in adolescents with benign

ovarian cysts. J Pediatr Surg. 47(3):577-80, 2012

5- Kirkham YA, Kives S: Ovarian cysts in adolescents: medical and

surgical management. Adolesc Med State Art Rev. 23(1):178-91, 2012

6- Tessiatore P, Guanà R, Mussa A, Lonati L, Sberveglieri M,

Ferrero L, Canavese F: When to operate on ovarian cysts in children? J

Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 25(5-6):427-33, 2012

PSU Volume 41 NO 04 OCTOBER 2013

Thromboprophylaxis

Thromboprophylaxis is utilized to

prevent and reduce the incidence of hospital-acquired life-threatening

venous thromboembolism (VTE) events such as deep venous thrombosis and

pulmonary embolism. The incidence of VTE in children has increased in

tertiary care centers. The presence of a central venous catheter is the

most prevalent risk factor for VTE in pediatric patients. Risk factors

associated with VTE include acute conditions such as major lower

extremity orthopedic surgery, spinal cord injury, major trauma to lower

extremity, lower extremity central venous catheter, acute infection,

burns and pregnancy. Chronic conditions include obesity, estrogen

containing medication, inflammatory bowel disease, nephrotic syndrome,

known thrombophilia. Other risk factors include past history of

previous DVT/PE or family history of VTE in first degree relatives.

Adolescent above the 14 years of age with above risk factors should

receive prophylaxis. Intervention for thromboprophylaxis includes early

and frequents ambulation, good hydration for low risk children;

mechanical prophylaxis using graduated compression antiembolic

stockings or sequential pneumatic compression for moderate risk; and

anticoagulant prophylaxis with enoxaparin or fractionated heparin for

high risk patients. For immobile patient sequential compression is

preferred. Contraindications for anticoagulation include intracranial

hemorrhage, acute stroke, uncontrolled hemorrhage, coagulopathy,

incomplete spinal cord injury, allergy and heparin induced

thrombocytopenia. Every institution managing children at high risk

should institute an algorithm of risk assessment and prophylaxis to

prevent VTE. Providing thromboprophylaxis to children is cost-effective.

References:

1- Jackson PC, Morgan JM: Perioperative thromboprophylaxis in children:

development of a guideline for management. Paediatr Anaesth.

18(6):478-87, 2008

2- Monagle P, Chalmers E, Chan A, DeVeber G, Kirkham F, Massicotte P,

Michelson AD; American College of Chest Physicians.

Antithrombotic therapy in neonates and children: American College of

Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th

Edition). Chest. 133(6 Suppl):887S-968S, 2008

3- Raffini L, Trimarchi T, Beliveau J, Davis D: Thromboprophylaxis in a

Pediatric Hospital: A Patient-Safety and Quality-Imrpovement

Intitative.Pediatrics. 127(5):e1326-32, 2011

4- Parker RI: Thromboprophylaxis in critically ill children: how should

we define the "at risk" child? Crit Care Med. 39(7):1846-7, 2011

5- Hanson SJ, Punzalan RC, Arca MJ, Simpson P, Christensen MA, Hanson

SK, Yan K, Braun K, Havens PL: Effectiveness of clinical guidelines for

deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis in reducing the incidence of venous

thromboembolism in critically ill children after trauma. J Trauma Acute

Care Surg. 72(5):1292-7, 2012

6- Sharma M, Carpenter SL: Thromboprophylaxis in a pediatric hospital.

Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 43(7):178-83, 2013

Mucopolysaccharidosis

Mucopolysaccharidosis (MPS) are a

group of metabolic disorders due to absence or malfunctioning of a

lysosomal enzyme needed to breakdown molecules called

glycosaminoglycans causing a storage lysosomal disease. Children with

MPS are at high-risk for significant perioperative mortality. Excessive

secretions, difficult or failed intubation, need for emergency

tracheotomy and intraoperative cardiac arrest have been described in

MPS patients. The most studied is MPS type I caused by a deficiency of

lysosomal enzyme alpha-L-iduronidase producing accumulation of dermatan

sulfate and heparan sulfate in the lysosomes. There is a spectrum of

clinical disease involvement depending on age of onset, progression,

cognitive involvement and organ involvement. Management of children

with MPS type I include hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and

recombinant human alpha-L-idurodinase enzyme replacement.

Disease-related airway issues have been shown to increase the risk of

transplant in MPS type I. Many deaths associated to MPS I are due to

upper airway obstruction encountered during anesthetic care specially

in children with the most severe phenotype. Numerous airway problems

have been reported, including obscured airway landmarks owing to excess

glycosaminoglycan deposition, copious thick secretions, narrow stiff

airways, and difficulty oxygenating owing to glycosaminoglycan

deposition within alveoli. Surgical mortality may be greater in these

undiagnosed patients who are unlikely to be referred to

anesthesiologists with expertise in managing difficult airways or to

undergo other precautionary measures. Physicians should become familiar

with the physical characteristics and surgical history that suggest MPS

disorders and refer such patients to geneticists for evaluation before

surgery.

References:

1- Arn P, Wraith JE, Underhill L: Characterization of surgical

procedures in patients with mucopolysaccharidosis type I: findings from

the MPS I Registry. J Pediatr. 154(6):859-64.e3, 2009

2- Munoz-Rojas MV, Bay L, Sanchez L, van Kuijck M, Ospina S, Cabello

JF, Martins AM: Clinical manifestations and treatment of

mucopolysaccharidosis type I patients in Latin America as compared with

the rest of the world. J Inherit Metab Dis. 34(5):1029-37, 2011

3- Osthaus WA, Harendza T, Witt LH, et al: Paediatric airway management

in mucopolysaccharidosis 1: a retrospective case review. Eur J

Anaesthesiol. 29(4):204-7, 2012

4- Arn P, Whitley C, Wraith JE, Webb HW, Underhill L, Rangachari L, Cox

GF: High rate of postoperative mortality in patients with

mucopolysaccharidosis I: findings from the MPS I Registry. J Pediatr

Surg. 47(3):477-84, 2012

5- Kirkpatrick K, Ellwood J, Walker RW: Mucopolysaccharidosis type I

(Hurler syndrome) and anesthesia: the impact of bone marrow

transplantation, enzyme replacement therapy, and fiberoptic intubation

on airway management. Paediatr Anaesth. 22(8):745-51, 2012

6- Leboulanger N, Louis B, Fauroux B: The acoustic reflection method

for the assessment of paediatric upper airways. Paediatr Respir Rev.

2013 May 13

Trichilemmal Cyst

Cystic lesions of the skin in children

are fairly common. Most cases are either sebaceous or pilomatrixoma

cysts. Cysts where keratinization occurs without keratohyaline granules

derived from the follicular isthmus of the external root sheath of the

hair follicle are called trichilemmal or pillar cysts. Trichilemmal

cysts occur most commonly in the scalp due to the dense hair follicle

concentration. Face, trunks, back and forehead are the other common

site in that order. Trichilemmal cysts can occur as sporadic lesions or

in hereditary-familial settings with autosomal dominant transmission.

Though almost always benign, malignant transformation can occur rarely.

They may be locally aggressive becoming large and ulcerated.

Proliferating trichilemmal tumor is a solid cystic neoplasm that shows

differentiation similar to that of the isthmus of the hair follicle.

Trichilemmal cysts are usually a solitary intradermal or subcutaneous

lesions. The cyst is lined by stratified squamous epithelium.

They can grow to large sizes. Management of trichilemmal cyst consists

of surgical excision. The cytologic diagnosis of pilar cysts is

important because these cysts recur if incompletely excised and often

undergo transformation to pilar tumors.

References:

1- Adachi N, Yamashita T, Ito H: Differential diagnosis of scalp trichilemmal cyst on MRI. Dermatology. 193(3):263-5, 1996

2- Shet T, Rege J, Naik L: Cytodiagnosis of simple and proliferating trichilemmal cysts. Acta Cytol. 45(4):582-8, 2001

3- Nakamura M, Toyoda M, Kagoura M, Higaki S, Morohashi M:

Ultrastructural characteristics of trichilemmal cysts: report of two

cases. Med Electron Microsc. 34(2):134-41, 2001

4- Garg PK, Dangi A, Khurana N, Hadke NS: Malignant proliferating

trichilemmal cyst: a case report with review of literature. Malays J

Pathol. 31(1):71-6, 2009

5- Ibrahim AE, Barikian A, Janom H, Kaddoura I: Numerous recurrent

trichilemmal cysts of the scalp: differential diagnosis and surgical

management. J Craniofac Surg. 23(2):e164-8, 2012

6- Seidenari S, Pellacani G, Nasti S, Tomasi A, Pastorino L, Ghiorzo P,

Ruini C, Bianchi-Scarrà G, Pollio A, Mandel VD, Ponti G:

Hereditary trichilemmal cysts: a proposal for the assessment of

diagnostic clinical criteria. Clin Genet. 84(1):65-9, 2013

PSU Volume 41 NO 06 NOVEMBER 2013

Atrophic Testis

Atrophic testes refer to a testis that has diminished in size

and is accompanied by loss of function. An atrophic testis can be

the result of perinatal torsion, cryptorchidism, trauma, previous

surgical procedure, orchitis and steroid use. Most atrophic testes are

abnormal due to a mechanical event shunting circulation rather than

maldevelopment or iatrogenic. Anabolic steroids can cause testicular

atrophy by reducing the amount of luteinizing hormone produced by the

pituitary gland. Repair of inguinal hernia after incarceration can also

cause testicular atrophy if vascular testicular occlusion occurred for

en extended period of time. Testicular atrophy can occur in almost 50%

of cases of non-palpable undescended testes. During perinatal descent

the testis circulation is entrapped causing the atrophy or vanishing of

the testis. They have sometimes been called vanishing testes

since a remnant nubbin is found during inguinal or abdominal

exploration. Very few of these remnants contains seminiferous tubules

and even fewer shows viable germ cells. Contralateral testicular

hypertrophy strongly indicates an atrophic testis in the other side.

Ultrasonography can determine the significant smaller size of the

affected testis and determine if is hypoechoic, a sonographic

characteristic of the atrophic testis. The management of the atrophic

testis is controversial. Removal of the remnant and placement of a

prothesis is an alternative in children. With growth this prothesis

will need replacement, hence placement during final adolescent growth

years is more prudent. The risk of malignant degeneration of the

testicular remnant is extremely low to justify surgical removal.

References:

1- Wood HM, Elder JS: Cryptorchidism and Testicular Cancer: Separating Fract from Fiction. J Uro 181 (2): 452-461, 2009

2- Antic T, Hyjek EM, Taxy JB: The Vanishing Testis. A

histomorphologic and clinical assessment. AM J Clin Pathol. 136:

872-880, 2011

3- Cortes D, Thorup J, Petersen BL: Testicular neoplasia in

undescended testes of cryptorchid boys-does surgical strategy have an

impact on the risk of invasive testicular neoplasia? Turk J Pediatr. 46

Suppl:35-42, 2004

4- Chu L, Averch TD, Jackman SV: Testicular infarction as a sequela of inguinal hernia repair. Can J Urol. 16(6):4953-4, 2009

5- Shibata Y, Kojima Y, Mizuno K, Nakane A, Kato T, Kamisawa H,

Kohri K, Hayashi Y: Optimal cutoff value of contralateral testicular

size for prediction of absent testis in Japanese boys with nonpalpable

testis. Urology. 76(1):78-81, 2010

6- Vijayaraghavan SB: Sonographic localization of

nonpalpable testis: Tracking the cord technique. Indian J Radiol

Imaging. 21(2):134-41, 2011

Tension Gastrothorax

The term tension gastrothorax originally appeared in the

literature as a complication of traumatic rupture of the diaphragm

producing mediastinal shift due to a distended intrathoracic stomach.

Congenital or acquired diaphragmatic defects can cause a tension

pneumothorax. The two groups of children that can be affected by a

tension gastrothorax include those with congenital diaphragmatic hernia

with late presentation and traumatic diaphragmatic hernias the result

of a previous accident. Most cases of tension gastrothorax occur around

the five years of age in cases with an existing congenital

defect. Vast majority are left-sided because the liver buttresses the

right side. Increased intraabdominal pressure or negative intrathoracic

pressure leads to herniation of the stomach into the chest. Respiratory

symptoms initially followed by abdominal pain and vomiting develops.

Other findings are tracheal deviation, reduced breaths sound, dullness

or resonance and a displace cardiac apex. Tension gastrothorax can be

erroneously interpreted as a tension pneumothorax leading to increase

morbidity and mortality during treatment. The chest film can be

diagnostic demonstrating a large air-filled structure with or without a

fluid level within the left hemithorax causing apical collapse of the

lung. Emergency management requires initial decompression with a

large-bore nasogastric tube. If this fails transthoracic needle

decompression of the stomach can be tried. Urgent definitive management

requires surgical reduction of the intrathoracic stomach and repair of

the diaphragmatic defect which can be accomplished preferably by

laparotomy as it hasten quick reduction of stomach and repair of the

diaphragmatic defect. Thoracotomy or thoracoscopy has also been

utilized less frequently. Morbidity relates to pulmonary collapse,

shock, bowel injury and sepsis due to gastric perforation in the thorax.

References:

1- Rathinam S, Margabanthu G, Jothivel G, Bavanisanker T:

Tension gastrothorax causing cardiac arrest in a child. Interact

Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 1(2):99-101, 2002

2- Zedan M, El-Ghazaly M, Fouda A, El-Bayoumi M: Tension gastrothorax:

a case report and review of literature. J Pediatr Surg. 43(4):740-3,

2008

3- Salim F, Ramesh V: Tension gastrothorax: a rare complication. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 19(5):325-6, 2009

4-Hooker R, Claudius I, Truong A: Tension gastrothorax in a child

presenting with abdominal pain. West J Emerg Med. 13(1):117-8, 2012

5- Gagg JW, Savva A: Tension gastrothorax: a rare cause of breathlessness. Emerg Med J. 30(6):500, 2013

6- Ng J, Rex D, Sudhakaran N, Okoye B, Mukhtar Z: Tension gastrothorax

in children: Introducing a management algorithm. J Pediatr Surg.

48(7):1613-7, 2013

Adrenalectomy in Wilms Tumor

Wilms tumor or nephroblastoma is the most common

intraabdominal malignant solid tumor in children. It is managed with

surgery, adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Surgical management

consists of radical nephrectomy when appropriate in many cases removing

the adrenal gland concomitantly with the tumor. Adrenal involvement in

patients with Wilms tumor is rare and difficult to predict. The

decision to remove the ipsilateral adrenal gland has been left to the

judgement of the operating surgeon at the time of nephrectomy, and is

likely based on the size and location of the primary tumor, ease of

adrenalectomy, and suspicion for adrenal involvement Routine

adrenalectomy does not confer a benefit for oncologic control (event

free survival) when it is feasible to spare the adrenal gland.

Intraoperative tumor spillage rates are higher in patients undergoing

concomitant adrenalectomy. Patients in whom adrenalectomy was performed

tended to have larger tumors than those in whom the gland was left in

situ. The histopathologic status of the adrenal gland with tumor does

not directly affect the oncologic outcome. Based on the low rate of

adrenal involvement, and lack of apparent oncologic benefit to

adrenalectomy concurrent with nephrectomy routine adrenalectomy does

not appear to be mandatory. Preserving the adrenal gland was not

associated with an increased risk of local recurrence. The above

appears to hold truth to renal cell carcinoma management in adults.

References:

1- Yap SA, Alibhai SM, Abouassaly R, Timilshina N, Finelli A: Do we

continue to unnecessarily perform ipsilateral adrenalectomy at the time

of radical nephrectomy? A population based study. J Urol.

187(2):398-404, 2012

2- Gow KW, Barnhart DC, Hamilton TE, Kandel JJ, Chen MK, Ferrer FA,

Price MR, Mullen EA, Geller JI, Gratias EJ, Rosen N, Khanna G, Naranjo

A, Ritchey ML, Grundy PE, Dome JS, Ehrlich PF: Primary nephrectomy and

intraoperative tumor spill: report from the Children's Oncology Group

(COG) renal tumors committee. J Pediatr Surg. 48(1):34-8, 2013

3- Tsui KH, Shvarts O, Barbaric Z, Figlin R, de Kernion JB, Belldegrun

A: Is adrenalectomy a necessary component of radical nephrectomy? UCLA

experience with 511 radical nephrectomies. J Urol. 163(2):437-41,

2000

4- Moore K, Leslie B, Salle JL, Braga LH, Bägli DJ,

Bolduc S, Lorenzo AJ: Can we spare removing the adrenal gland at

radical nephrectomy in children with wilms tumor? J Urol. 184(4

Suppl):1638-43, 2010

5- Kieran K, Anderson JR, Dome JS, Ehrlich PF, Ritchey ML, Shamberger

RC, Perlman EJ, Green DM, Davidoff AM: Is adrenalectomy necessary

during unilateral nephrectomy for Wilms Tumor? A report from the

Children's Oncology Group. J Pediatr Surg. 48(7):1598-603, 2013

6- Green DM: The evolution of treatment for Wilms tumor. J Pediatr Surg. (48): 14-19, 2013

PSU Volume 41 No 06 DECEMBER 2013

Granular Cell Tumor

Granular cell tumor, also

known as Abrikossoff tumor, is a very infrequent benign neoplasm

affecting all parts of the body, but with a predilection for the head

and neck region. In the head and neck region most cases are localized

in the oral cavity, especially the tongue. Granular cell tumor (GCT) is

twice as common in females as in males. These tumors usually present as

a solitary slow-growing ulcerated nodular mass located mainly in the

subcutaneous tissue. The lesion is mobile and not painful with mild

pruritus. Multiple development of granular cell tumor can be seen

associated with Noonan syndrome and Neurofibromatosis. In children, the

most frequent presentation of GCT is congenital epulis, arising from

the median ridge of the newborn maxilla. The histogenesis of the tumor

is from neural or nerve sheath cells. Histopathology of the tumor shows

polygonal cells arranged in sheets with granular eosinophil cytoplasm

and small nuclei. The granularity of the tumor cells is due to

accumulation of secondary lysosome in the cytoplasm of the cells. An

aggressive malignant variant of granular cell tumor is extremely rare.

There are no well-defined criteria for the diagnosis of malignancy.

Tumor size > 5 cm, rapid growth, vascular invasion, necrosis and

cell spindling are important indicators of atypia pertaining

malignancy. Occurrence of metastasis is the only accepted criteria of

malignancy. Malignancy when present is associated with a poor

prognosis. Management of granular cell tumor consists of complete

surgical excision. Recurrence is uncommon unless surgical excision has

been incomplete. Follow-up must be prolonged.

References:

1- Finck C, Moront M, Newton C, Timmapuri S, Lyons J, Rozans M, de

Chadarevian JP, Halligan G: Pediatric granular cell tumor of the

tracheobronchial tree. J Pediatr Surg. 43(3):568-70, 2008 2- Dupuis C,

Coard KC: A review of granular cell tumours at the University Hospital

of the West Indies: 1965-2006. West Indian Med J. 58(2):138-41,

2009

3- Ramaswamy PV, Storm CA, Filiano JJ, Dinulos JG: Multiple granular

cell tumors in a child with Noonan syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol.

27(2):209-11, 2010

4- Torre M, Yankovic F, Herrera O, Borel C, Latorre JJ, Aguilar P,

Varela P: Granular cell tumor mimicking a subglottic hemangioma. J

Pediatr Surg. 45(12):e9-11, 2010

5- Nasser H, Ahmed Y, Szpunar SM, Kowalski PJ: Malignant granular cell

tumor: a look into the diagnostic criteria. Pathol Res Pract.

207(3):164-8, 2011

6- Lahmam Bennani Z, Boussofara L, Saidi W, Bayou F, Ghariani N,

Belajouza C, Sriha B, Denguezli M, Nouira R: [Childhood cutaneous

Abrikossoff tumor]. Arch Pediatr. 18(7):778-82, 2011

Watersport Injuries

Injuries related to personal watercraft have increased

dramatically over the past several years, becoming one of the leading

causes of recreational watersport injuries. Median age of the accident

is generally 10 years. Towed tubing which involves riding an inflatable

tube while being pulled behind a boat is the most prevalent trauma

mechanism in watersport injury. This is followed by accidents involving

motorboats and accidents involving a personal watercraft. Towed tubing

accidents has a longer hospital stay since this mechanism account for

an increased morbidity in comparison with other recreational

activities. It is strongly suggested that wearing protective gear and

protective wet suit should be recommended for children involved in

watercraft and watersport activities. Mandatory speed limit regulations

should be considered to decrease the risk of serious injury due to the

specific category of the watercraft injury. Propeller injuries can

produce an increase incidence of distal limb amputations. Almost 20% of

all boating fatalities and 8% of all non-fatal injuries are associated

with accidents in which alcohol or drugs were contributing factors. Jet

ski accidents tended to result in more serious injuries (closed-head

injuries, hollow and solid viscus injuries, chest trauma, spinal

injuries leading to paralysis, and death) than those sustained in

accidents with small boats. It is also recommended life vest and easily

visible personal floating devices be used by children and adolescent

riding watercrafts. Increased use of personal floating device,

avoidance of dangerous currents, and less alcohol use by operators and

passengers of all types of watercraft would result in a reduction in

watercraft-related drowning. Government statistics on personal

watercraft injuries do not accurately reflect the true incidence and

economic impact of such trauma. Mandatory educational programs and

increased legislation to improve personal watercraft safety should be

promoted.

References:

1- Browne ML, Lewis-Michl EL, Stark AD: Watercraft-related drownings

among New York State residents, 1988-1994. Public Health Rep.

118(5):459-63, 2003

2- Kim CW, Smith JM, Lee A, Hoyt DB, Kennedy F, Newton PO, Meyer RS:

Personal watercraft injuries: 62 patients admitted to the San Diego

County trauma services. J Orthop Trauma. 17(8):571-3, 2003

3- Rubin LE, Stein PB, DiScala C, Grottkau BE: Pediatric trauma caused

by personal watercraft: a ten-year retrospective. J Pediatr Surg.

38(10):1525-9, 2003

4- White MW, Cheatham ML: The underestimated impact of personal watercraft injuries. Am Surg. 65(9):865-9, 1999

5- Beierle EA, Chen MK, Langham MR Jr, Kays DW, Talbert JL: Small watercraft injuries in children. Am Surg. 68(6):535-8, 2002

6- Keijzer R, Smith GF, Georgeson KE, Muensterer OJ: Watercraft and

watersport injuries in children: trauma mechanisms and proposed

prevention strategies. J Pediatr Surg. 48(8):1757-61, 2013

Stuck Catheter

Totally implantable venous access devices are essential for

providing therapy for children with cancer, long-term medication,

parenteral nutrition and sampling. Unfortunately they are no without

complications during insertion, maintenance and removal. Removal occurs

with resolution of disease, dysfunction or infection of the device. One

of the most feared complications during removal is the stuck catheter.

The catheter after a prolonged period of use is fixed to the vessel

wall. The catheter is stuck in strong connective fibrous tissue matrix

to the vessel wall. This occurs more commonly with polyurethane

catheter than silicone catheters. In fact polyurethane catheters are

contraindicated if its going to be in use for more than 18 months. The

management of a stuck catheter should follow a course of action

encompassing dissection along the subcutaneous tract until the entrance

to the vein is encountered. A stiff guide wire can be inserted into the

lumen of the catheter and instead of applying a "pull-out" force, use a

"push-in" force to detach the catheter from the deep central vein. When

the forced "pull-out" maneuver is used, the catheter can stretch and

will likely break if the tension exceeds the tolerance of the catheter.

The soft J tip of the guide-wire prevents puncture of the catheter or

the wall of the heart and vein during the maneuver In other occasion

the catheter will brake during removal and either stay stuck in the

vein or embolize. In such situation endovascular retrieval by

interventional radiologist of the segment of left catheter is indicated

due to the inherent risk of infection and venous thrombosis. Have found

useful after passing the wire to the stuck catheter cleaning the

adherence of fibrin reintroducing a new sheath through the catheter

fluoroscopically-guided.

References:

1- Wilson GJ, van Noesel MM, Hop WC, van de Ven C: The catheter is

stuck: complications experienced during removal of a totally

implantable venous access device. A single-center study in 200

children. J Pediatr Surg. 41(10):1694-8, 2006

2- Field M, Pugh J, Asquith J, Davies S, Pherwani AD: A stuck

hemodialysis central venous catheter. J Vasc Access. 9(4):301-3, 2008

3- Huang SC, Tsai MS, Lai HS: A new technique to remove a "stuck"

totally implantable venous access catheter. J Pediatr Surg.

44(7):1465-7, 2009

4- Mortensen A, Afshari A, Henneberg SW, Hansen MA: Stuck long-term

indwelling central venous catheters in adolescents: three cases and a

short topical review. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 54(6):777-80, 2010

5- Hong JH: A breakthrough technique for the removal of a hemodialysis

catheter stuck in the central vein: endoluminal balloon

dilatation of the stuck catheter. J Vasc Access. 12(4):381-4, 2011

6- Ryan SE, Hadziomerovic A, Aquino J, Cunningham I, O'Kelly K, Rasuli

P: Endoluminal dilation technique to remove "stuck" tunneled

hemodialysis catheters. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 23(8):1089-93, 2012