PSU Volume 56 NO 01 JANUARY 2021

Central Venous Catheter Tip Placement

Central venous catheters (CVC) are essential for providing

long-term chemotherapy for cancer, total parenteral nutrition, central

venous pressure monitoring, secure regular blood sampling, and

prolonged intravenous management in children. Using ultrasound and

Seldinger technique, the internal jugular, external jugular, cephalic

or subclavian vein are usually cannulated as entrance points. The

anatomic position of the tip of the CVC is of upmost importance

to avoid dysrhythmias, thrombosis, valvular insufficiency, inaccurate

venous pressure monitoring, tricuspid valve damage, and perforation of

the right atrium (RA), right ventricle or superior vena cava (SVC)

resulting in cardiac tamponade. Tips located outside the heart are

associated with thrombosis of the cava or its tributaries, inadvertent

infusion into nontarget vessels, catheter dysfunction, erosion of the

catheter into the lung or bronchus and risk of perforation with

hemothorax. Catheter angulation, curvature or looping is a major risk

for perforation. The recommended position of the tip of the CVC is just

above the superior vena cava-right atrial junction parallel to the

SVC to prevent serious complications. Radiographic and

fluoroscopy methods are the standard for defining tip position follow

very closely by ultrasound and EKG. Several radiographic landmarks have

been used to determine the exact position of the tip of the catheter in

the SVC-RA junction. These include the right tracheobronchial angle and

the carina. The right tracheobronchial angle has less clinical

applicability as radiologist find difficult to identify in some chest

films. The carina has several advantages as radiologic landmark of the

catheter tip: it does not move with pathologic changes in the lung, it

is positioned in the center of the body and it can be identified easily

even in poor quality chest films. In adolescent and young adults a

point approximately two vertebral body units below the carina was found

as the landmark of the cavoatrial junction. In order to place the

catheter tip at the level of the carina several external landmarks must

be used to cut the proper length of catheter during insertion. The CVC

tip can be reliably placed near the carina level using the external

landmarks of the sternal head of the right clavicle and a perpendicular

line connecting both nipples. The catheter distance should be measured

from the insertion point to midpoint the distance between these two

landmarks substrated by 0.5 cm and cut. The insertion depth is

determined placing the CVC over the sterilized skin from the insertion

point to the midpoint of the perpendicular line joining the sternal

head of the right clavicle and the line connecting both nipples.

Alternatively, the depth of insertion of the catheter can be determined

by the distance from the skin puncture to the second intercostal space

(sternal angle of Lewis). The length of the CVC using either the carina

or SVC-RA junction as measured by thoracic CT-Scan correlates with the

patient age and body surface area and formulas for each catheter length

have been devised previously. The carina is still an easily sighted and

clear radiological landmark in children to confirm that the CVC tip is

outside the pericardial reflection. In neonates the carina is not

always located above the pericardium, therefore, the carina could not

be an appropriate landmark for CVC placement. In all cases, a chest

film is mandatory after CVC placement to determine tip position and

associated complications of punctured.

References:

1- Andropoulos DB, Bent ST, Skjonsby B, Stayer SA: The Optima Length of

Insertion of Central Venous Catheters for Pediatric Patients. Anesth

Analg. 93: 883-886, 2001

2- Yoon SZ, Shin JH, Hahn S, et al: Usefulness of the carina as a

radiographic landmark for central venous catheter placement in

paediatric patients. Br J Anaesth. 95(4): 514-517, 2005

3- Baskin KM, Jimenez RM, Cahill AM, Jawad AF, Towbin RB: Cavoatrial

Junction and Central Venous Anatomy: Implications for Central Venous

Access Tip Position. J vasc Interv Radiol 19: 359-365, 2008

4- Na HS, Kim JT, Kim HS, et al: Practical anatomic landmarks for

determining the insertion depth of central venous catheter in

paediatric patients. Br J Anaesth. 102(6): 820-823, 2009

5-Witthayapraphakorn L, Khositseth A, Jiraviwatana T, et al:

Appropriate Length and Position of the Central Venous Catheter

Insertion via Right Internal Jugular Vein in Children. Indian Pediatr.

50:749-752, 2013

6- Perin G, Scarpa MG: Defining central venous line position in children: tips for the tip. J Vasc Access. 16(2): 77-86, 2015

7- Hoffmann S, Goedeke J, Konig TT, et al: Multivariate analysis on

complications of central venous access devices in children with cancer

and severe disease influenced by catheter tip position and vessel

insertion site (A STROBE-compliant study). Surgical Oncology. 34:

17-23, 2020

8- Maddali MM, Al-Shamsi F, Arora NR, Panchatcharam SM: The Optimal

Length of Insertion for Central Venous Catheters Via the Right Internal

Jugular Vein in Pediatric Cardiac Surgical Patients. J Cardiothoracic

and Vasc Anesth. 34: 2386-2391, 2020

Bilateral Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma

Of all thyroid cancers occurring in the USA, around 10%

occurs during the pediatric age. Almost 20% of all solid thyroid

nodules in children harbor a malignancy. The most common histological

type of thyroid malignancy found in children is papillary carcinoma,

which together with the less common follicular variety (< 5%)

comprise most cases of differentiated thyroid cancer in children.

Differentiated thyroid carcinoma arises from the thyroid follicular

cells. Papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC) in children is characterized

by a high incidence of regional lymph node metastasis at the time of

diagnosis (60%), along with a higher incidence of bilateral and

multifocal disease (30% and 65% respectively. In spite of this,

children are less likely to die from disease, with disease-specific

mortality less than 3%. The three most common risk factors identified

in children with PTC include exposure to ionizing radiation in the head

and neck area, a family history of thyroid cancer and a preoperative

diagnosis of Hashimoto thyroiditis. A variety of genetic disorders may

predispose to PTC including familial adenomatoid-polyposis, Carney

complex, Werner syndrome, DICER1 syndrome and hamartoma tumor syndrome.

The presence of lateral neck lymph node metastasis noted in

preoperative ultrasound studies is associated with an increase risk of

detectable bilateral PTC. FNA should be performed on any suspicious

lymph nodes in the lateral neck as confirmation of metastatic

involvement prior to lateral neck dissection. Of children diagnosed

preoperatively with unilateral disease, if the dominant tumor measured

greater than 2 cm a postoperative diagnosis of bilateral disease is

more likely. Children with occult bilateral disease are more likely to

have positive central compartment lymph node involvement, extranodal

extension of disease, extrathyroidal extension, lymphovascular invasion

and multifocal disease. Diffuse-sclerosing variant tumors is associated

with an increase of bilateral disease. Total thyroidectomy maximizes

disease-free survival, overall survival and quality-adjusted life

expectancy in children with PTC compared with lobectomy. Almost

one-fourth of children have occult contralateral disease with a high

risk for persistent disease if a total thyroidectomy is not performed

at the time of diagnosis. Lesser thyroid resection than total

thyroidectomy is associated with as high as 10-fold greater recurrences

rates. Inadequate lymph node dissections in patients with clinically

positive nodes increase the need for subsequent intervention 3-fold.

Addition of central lymph node dissection to total thyroidectomy in PTC

decrease recurrence rate to less than 5%at ten

years.

References:

1- Baumgarten H, Jenks CM, Isaza A, et al: Bilateral papillary thyroid

cancer in children: Risk factors and frequency of postoperative

diagnosis. J Pediatr Surg. 55(6):1117-1122, 2020

2- Christison-Lagay ER, Beartschiger RM, Dinauer C, et al: Pediatric

differentiated thyroid carcinoma: An update from the APSA Cancer

Committee. J Pediatr Surg.http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedsurg2020.05.003,

2020

3- Hay ID, Johnson TR, Kaggal S, et al: Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma

(PTC) in Children and Adults: Comparison of Initial Presentation and

Long-Term Postoperative Outcome in 4432 Patients Consecutively Treated

at the Mayo Clinic During Eight Decades (1936-2015). World J Surg.

42(2):329-342, 2018

4- Qu N, Zhang L, Wu WL, et al: Bilaterality weighs more than

unilateral multifocality in predicting prognosis in papillary thyroid

cancer. Tumour Biol. 37(7):8783-9, 2016

5- Lee YS, Lim YS, Lee JC, et al: Clinical implications of bilateral

lateral cervical lymph node metastasis in papillary thyroid cancer: a

risk factor for lung metastasis. Ann Surg Oncol. 18(12):3486-92, 2011

Zenker Diverticulum

Zenker diverticulum is considered the most common

diverticulum of the esophagus. It is usually seen in the 6th to 8th

decade of life with only a few cases described in the pediatric age.

Zenker diverticulum is a protrusion of pharyngo-esophageal mucosa

through a weak zone in the posterior wall of the pharynx known as

Killian's triangle. It is an acquired hernia of the posterior

pharyngeal mucosa membrane at the pharyngo-esophageal junction

occurring between fibers of the lower pharyngeal constrictor and

crico-pharyngeal muscles. Dysfunction of the cricopharyngeal muscle

plays a major role in the pathogenesis of the diverticulum. It is a

pulsion pseudodiverticulum since is associated with high intraluminal

pressure and does not contain all the layers of the esophagus. Being a

pseudodiverticulum there is involvement of only the mucosal layer. They

are more common in males and present more frequently on the left side.

Zenker diverticulum causes dysphagia, a sensation of food sticking in

the throat, noisy deglutition, regurgitation of undigested food, cough,

aspiration, chronic foreign body impaction and halitosis. Over time

patients may present weight loss due to chronic dysphagia. Esophagogram

(barium swallow is the gold standard), US or CT-Scan with oral contrast

of the neck and proximal thorax are diagnostic, revealing a

diverticular pouch filled with air, debris and food particles

compressing the trachea. Zenker diverticulum is classified by their

longitudinal size into small (diameter less than 2 cm), medium

(diameter 2-4 cm), and large (diameter > 4 cm). Zenker diverticulum

is associated with Marfan syndrome due to the abnormal weak wall

related to the connective tissue disorder. The differential diagnosis

includes a congenital crico-pharyngeal diverticulum, duplication of the

esophagus, traction diverticulum, a false diverticulum above a

congenital stenosis, traumatic pseudodiverticulum of the pharynx in

newborns (perforation by nasogastric tube), and a postoperative

diverticulum after repair of tracheo-esophageal fistula. Management of

a Zenker diverticulum depends on the location, symptoms and size of the

diverticulum. Endoscopy stapling or laser resection, diverticulectomy,

cricopharyngeal myotomy or diverticulopexy are several procedures

performed for Zenker diverticulum. Myotomy is the mainstay of treatment

with favorable outcomes in more than 80% of patients with a reduced

recurrence rate. Endoscopic management is not recommended in large

diverticula because of incomplete emptying of pouch

remnants.

References:

1- Gorkem SB, Yikilmaz A, Coskun A, Kucukaydin M: A pediatric case of

Zenker diverticulum: imaging findings. Diagn Interv Radiol 15: 207-209,

2009

2- Patron V, Godey B, Aubry K, Jegoux F: Case report. Endoscopic

treatment of pharyngo-esophageal diverticulum in child. Internat J

Pediatr Otorhinolaryng. 74: 694-697, 2010

3- Abu-Omar A, Miller C, McDermott AL: Acquired pharyngoesophageal

diverticulum in childhood. J Laryng & Otology. 124: 1298-1299, 2010

4- Lindholm EB, Hansbourgh F, Upp Jr JR, Cilloniz R, Lopoo J:

Congenital esophageal diverticulum - A case report and review of

literature. J Pediatr Surg. 48: 665-668, 2013

5- Bergeron JL, Chheri DK: Indications and Outcomes of Endoscopic CO2

Laser cricopharyngeal Myotomy. Larynsgoscope 124(4): 950-954, 2014

6- Crawley B, Dehom S, Tamares S, et al: Adverse Events after Rigid and

Flexible Endoscopic Repair of Zenker's Diverticula: A Systematic Review

and Meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 161(3):388-400, 2019

PSU Volume 56 NO 02 FEBRUARY 2021

Congenital Short Bowel Syndrome

Short bowel syndrome is a clinical disorder characterized by

diarrhea, malabsorption and needs of parenteral nutrition for life

support. In newborns, short bowel syndrome is most commonly an acquired

disorder after surgical bowel resection due to conditions such as

necrotizing enterocolitis, gastroschisis, volvulus, extensive

aganglionosis in Hirschsprung's disease, or intestinal atresia. Born

with a short bowel known as congenital short bowel syndrome (CSBS) is a

very rare condition in newborns associated with a high mortality rate

and prognosis. According to autopsy reports, the length of the

small intestine as measured from Treitz to ileocecal valve correlates

with crown-to-heel length. The mean length of the small bowel in full

term infants is approximately 240 cm and increases to 600 cm in

adulthood. Short bowel syndrome manifests in newborns when the small

bowel length is less than 75 cm. Newborns with CSBS can be as short as

20 cm in length, with a mean length of 50 cm. The pathogenesis of CSBS

is poorly understood. CSBS occurs most often in association with

malrotation (> 96%). The normal elongation, rotation and herniation

of the small bowel is interrupted or delayed due to lack of space

between the developing digestive tube and umbilical celom. Other

believe is a defective neuroenteric development since intestinal

dysmotility is an important component of the syndrome. Children born

with CSBS have a loss of function nonsense mutation in the CLMP

(Coxsackie- and adenovirus receptor-like membrane protein). CLMP

encodes a tight-junction membrane protein of the bowel, located in

chromosome 11, and expressed during embryonic development. Mutations in

CLMP cause a recessive form of CSBS. In other patients a mutation in

FLNA gene was found in chromosome X, which encodes for a cytoskeletal

protein called filamin A that binds to actin. Other congenital

anomalies associated with CSBS include pyloric stenosis, appendiceal

agenesis, acheiria, dextrocardia, hemivertebrae and paten ductus

arteriosus. Clinically, most babies with CSBS develop bilious vomiting,

diarrhea, failure to thrive with signs/symptoms consistent with

intestinal obstruction. Onset of intestinal volvulus associated with

acute mesenteric ischemia is rare in these patients since a short bowel

length precludes twisting. CSBS is diagnosed by barium-contrast studies

and confirmed by exploratory laparotomy. Management of CSBS consist of

parenteral nutrition with early introduction of enteral nutrition. In

the event of failed adaptation and liver failure with reduced venous

access from treatment, transplantation becomes the hope for these

children. Survival beyond the first year with CSBS is 75% and

improving. Most common cause of death is

sepsis.

References:

1- Hasosah M, Lemberg DA, Skarsgard E, Schreiber R. Congenital short

bowel syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. Can J

Gastroenterol. 22(1):71-4, 2008

2- Van Der Werf C, Wabbersen TD, Hsiao NH, et al: CLMP is Required for

Intestinal Development, and Loss-of-Function Mutations Cause Congenital

Short-Bowel Syndrome. Gastroenterology 142: 453-462, 2012

3- Coletta R, Khalil BA, Morabito A. Short bowel syndrome in children:

surgical and medical perspectives. Semin Pediatr Surg. 23(5):291-7, 2014

4- Gonnaud L, Alves MM, Cremillieux C, et al: Two new mutations of the

CLMP gene identified in a newborn presenting congenital short-bowel

syndrome. Clinics and Research in Hepatology and gastroenterology 40:

e65-e67, 2016

5- Goulet O, Abi Nader E, Pigneur B, Lambe C. Short Bowel Syndrome as

the Leading Cause of Intestinal Failure in Early Life: Some Insights

into the Management. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 22(4):303-329,

2019

6- Negri E, Coletta R, Morabito A. Congenital short bowel syndrome:

systematic review of a rare condition. J Pediatr Surg. 55(9):1809-1814,

2020

Biliary Dyskinesia

Biliary Dyskinesia (BD) is characterized by an abnormal

gallbladder contractility identified using cholecystokinin-stimulated

hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) nuclear scans. BD is a

diagnosis of exclusion so other causes such as irritable bowel

syndrome, dyspepsia, GE reflux disease needs to be rule out. The

diagnosis is established when the gallbladder has an ejection fraction

less than 35% and the child has typical symptoms of biliary colic

without gallstones. Gallbladder dyskinesia is becoming the most common

indication for gallbladder removal in adults and pediatric population.

The most accepted pathogenesis of BD is uncoordinated contractions and

relaxation of both the gallbladder and sphincter of Oddi. Subsequent

distension of the gallbladder leads to inflammation, hypersensitivity

and dysfunction. 75% of affected cases are females, most cases

are white adolescents and almost 50% are obese. Major preoperative

symptoms in children with BD include nonspecific vague chronic right

upper quadrant/epigastric abdominal pain, nausea, postprandial pain,

fatty food intolerance, vomiting, constipation and diarrhea in this

order of frequency. Children with symptoms and BD undergo a series of

preoperative studies without significant pathologic findings such as

US, CT-Scan, MRI, UGIS and upper/lower GI endoscopy. Most of this cases

are referred by pediatric gastroenterologist after trying several

medical management options. Initially more than 80% claim pain

improvement after cholecystectomy, but two years or more after surgery

30-40% continue with similar symptoms. The difference between short and

long-term results may be due to true recurrence of symptoms or

inaccurate reporting by parents who wants to please the surgeon.

Two-third of gallbladders removed due to BD shows chronic

cholecystitis. Patients with chronic inflammation are more likely to

persist with symptoms at long-term follow-up. An ejection fraction

below 15% is usually associated with a higher resolution of symptoms

after cholecystectomy. BMI percent, pain during CCK administration

during the HIDA scan and presence of chronic cholecystitis does not

predict which patient will have short or long-term improvement in

symptoms. Factors independently associated with short term pain

improvement after cholecystectomy includes shorter duration of pain

before surgery, history of vomiting preop, no history of fevers or

obstructive sleep apnea. Factors independently associated with

short-term complete symptoms, resolution includes history of epigastric

pain and lower GI disease. Longer duration of symptoms predicts poor

outcome after cholecystectomy in BD. Symptoms of functional dyspepsia

overlap with symptoms of BD in children. There is no well-defined

nonsurgical management of BD. Some researchers advocate medical over

surgical management of BD since BD is not a life threatening condition,

there are no serious complications and some children continue to

experience symptoms after cholecystectomy. With persistent abdominal

pain after cholecystectomy there is a high index of suspicion for

sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Studies comparing cholecystectomy to

nonsurgical medical management show same results in both

groups.

References:

1- Haricharan RN, Proklova LV, Aprahamian CJ, et al: Laparoscopic

cholecystectomy for biliary dyskinesia in children provides durable

symptoms relief. J Pediatr Surg. 43: 1060-64, 2008

2- Lacher M, Yannam GR, Muenterer OJ, et al: Laparoscopic

cholecystectomy for biliary dyskinesia in children: Frequency

increasing. J Pediatr Surg. 48: 1716-1721, 2013

3- Knott EM, Fike FB, Gasior AC, et al: Multi-institutional analysis of

long-term symptoms resolution after cholecystectomy for biliary

dyskinesia in children. Pediatr Surg Int 29: 1243-47, 2013

4- Mahida JB, Sulkowski JP, Cooper JN, et al: Prediction of symptoms

improvement in children with biliary dyskinesia. J Surg Research. 198:

393-399, 2015

5- Jones PM, Rosenman MB, Pfefferkorn MD, Rescorla FJ, Bennett Jr WE:

Gallbladde Ejection Fraction is Unrelated to Gallbladder Pathology in

Children and Adolescents. JPGN 63:71-75, 2016

6- Santuci NR, Hyman PE, Harmon CM, Schiavo JH, Hussain SZ: Biliary

Dyskinesia in Children: A Systematic Review. JPGN 64: 186-193, 2017

7- Coluccio M, Claffey AJ, Rothstein DH: Biliary Dyskinesia: Fat or

fiction?. Seminars Pediatr Surg.

Https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sempedsurg.2020.150947, 2020

8- Khan FA, Markwith N, Islam S: What is the role of the

cholecystokinin stimulated HIDA scan in evaluationg abdominal pain in

children?. J pediatr Surg. 55: 2653-2656, 2020

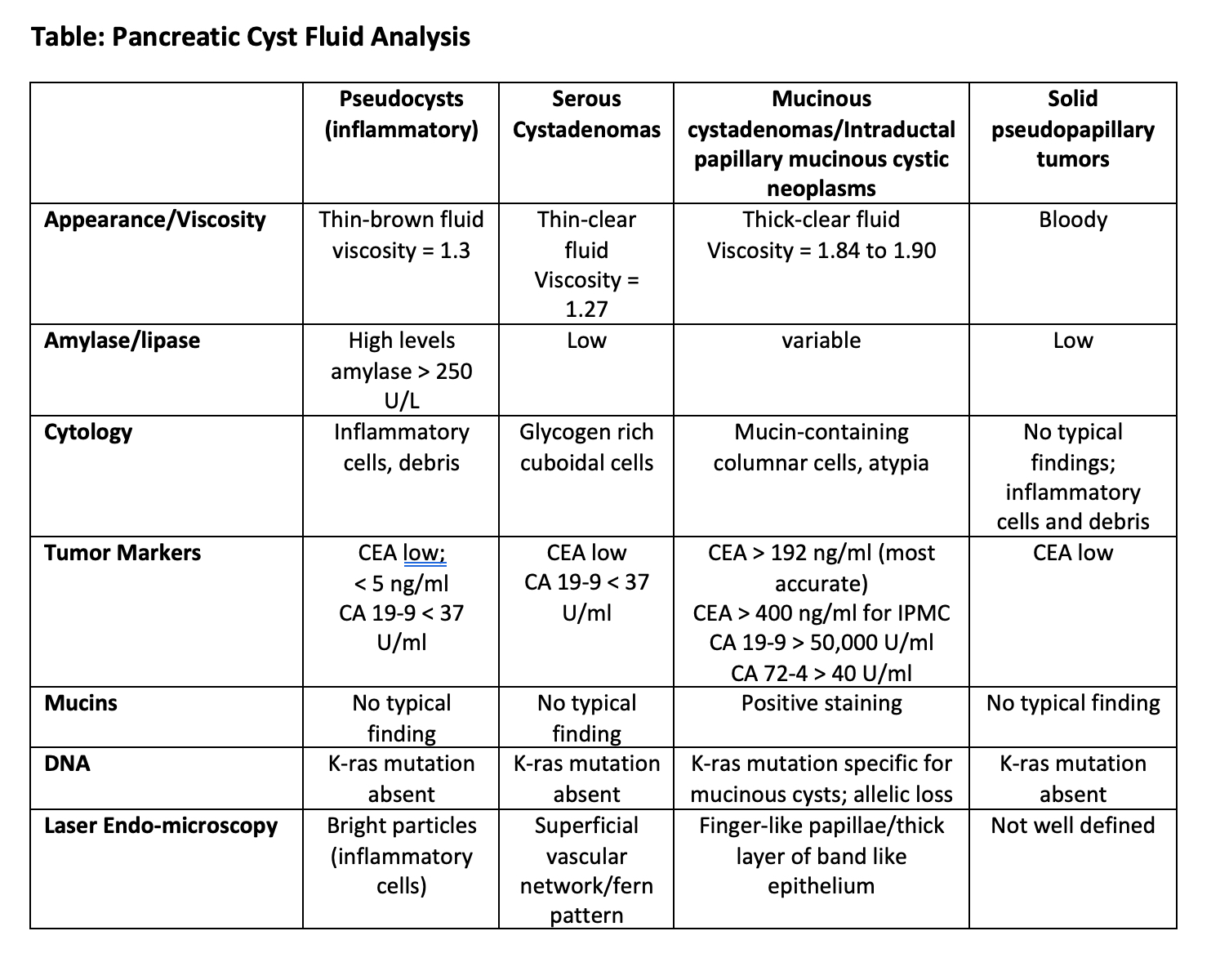

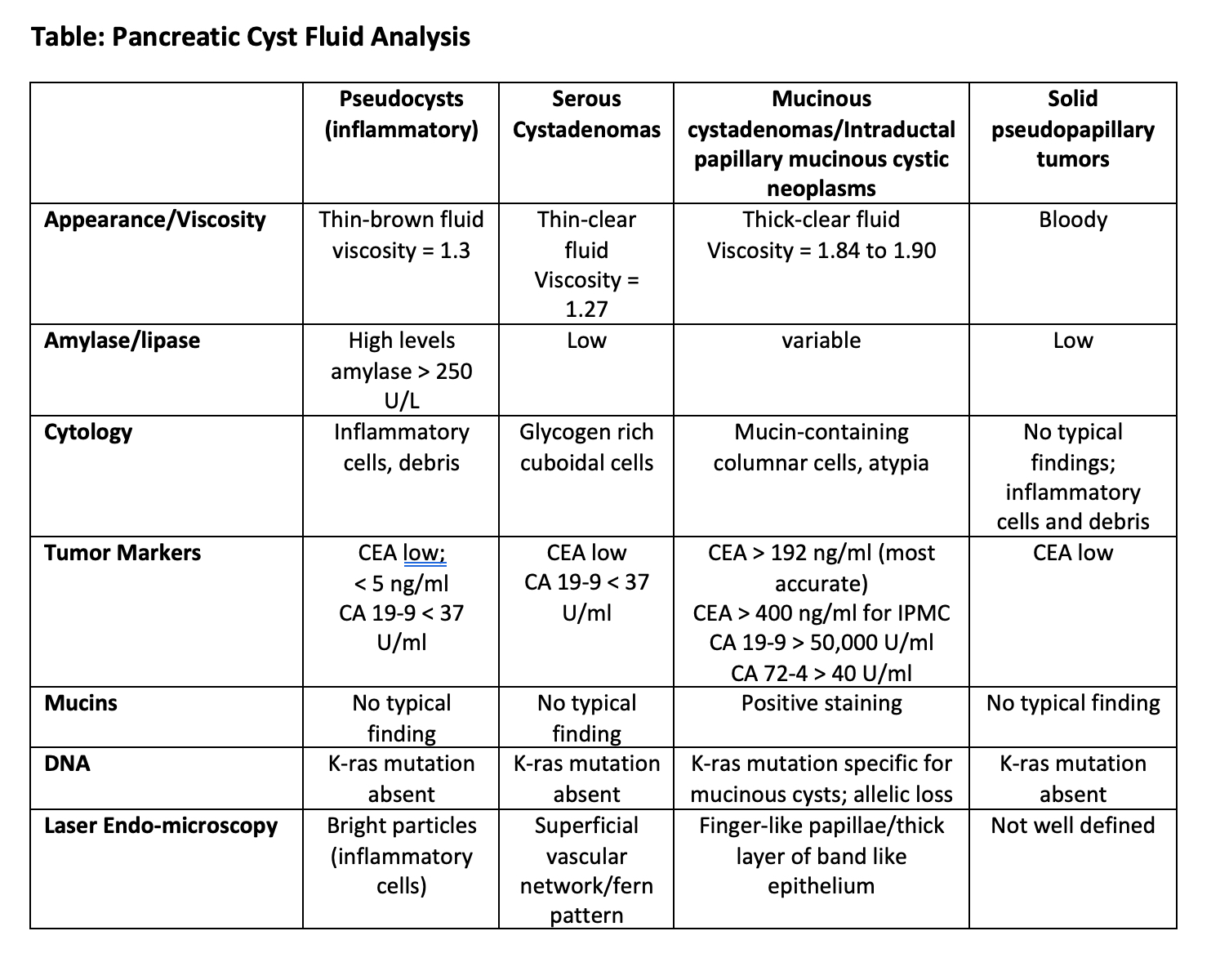

Pancreatic Cyst Fluid Analysis

The extensive use of ultrasound has uncovered

symptomatically as well as asymptomatic pancreatic cysts. The majority

of pancreatic cysts are found incidentally when abdominal imaging is

performed for other indications. Pancreatic cysts can either be simple

(retention) cysts, pseudocysts and cystic neoplasm. Cystic neoplasms

are further subdivided into serous cystadenomas, mucinous cystic

neoplasms, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms or papillary cystic

neoplasms. The majority of pancreatic cystic lesions identified are

mucinous cystic neoplasms. Since some of these pancreatic cysts can

develop into malignancy, a diagnosis performing aspiration and analysis

of the cyst fluid must be undertaken. Accurate diagnosis leads to

effective and standard management. This can be achieved using either

US- or CT-guided percutaneous aspiration or endoscopic ultrasound fine

needle aspiration. The diagnostic accuracy after aspiration is very

high (~95%). The fluid is analyzed for cytology, viscosity,

extracellular mucin, tumor markers (CEA, CA 19-9, CA 15-3, CA 72-4, CA

125), enzymes (amylase/lipase) and DNA quality/content or mutational

analysis. Mutational analysis can further characterize allelic

imbalances, loss of heterozygosity (LOH) and K-ras mutation. Estimates

of the cyst fluid volume can be approximated using the formula 4r3;

where r is the radius of the cyst. Imaging is the less accurate in the

diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions. Surgical resection is

recommended if a cyst has both a solid component and dilated main

pancreatic duct. Viscosity is lower in pseudocysts (1.3) and serous

cystadenomas (1.27), compared with mucinous cystadenoma (1.84) and

mucinous cystadenocarcinomas (1.90). CEA levels are high in mucinous

cystadenomas and very high in mucinous cystadenocarcinomas when

compared with pseudocysts and serous cystadenomas. Elevated CEA and

viscosity accurately predict mucinous cysts. The presence of

extracellular mucin is predictive of a mucinous neoplasm. Cytological

identification of extracellular mucin and CEA elevation are predictors

of mucinous neoplasm and malignancy. Cytology detects mucin containing

cells, malignant cells, glycogen-rich cuboidal cells, branching

papillae and abundant enucleate squamous cells and debris. Cytology is

diagnostic in less than 60% of pancreatic cysts. CA19-9 cyst fluid

levels above 50,000 U/ml are found in mucinous cystadenoma and

cystadenocarcinomas. Levels below 37 U/ml suggest serous cystadenomas

or pseudocysts. CA 19-9 is suitable for detection of malignancy but is

insensitive for premalignant lesions. CA72-4 cyst fluid levels above 40

U/ml are significantly high in mucinous cystic tumors. CEA levels

greater than 400 ng/ml are characteristic of mucinous tumors and

cystadenocarcinoma, while CEA levels less than 4 ng/ml are associated

with serous cystadenomas. Cyst fluid CEA is the most accurate test

available for diagnosis of mucinous cystic lesions of the pancreas with

a cut off value of 192 ng/ml for diagnosis. In some centers CEA is the

only tumor marker routinely use for diagnostic work-up. Amylase/lipase

high levels (above 250 U/L) are commonly seen in pseudocysts. Cyst

fluid amylase is of limited utility in evaluation of pancreatic cysts.

Low values are associated with a neoplastic tumor. DNA analysis has

found that a K-ras mutation followed by allelic loss is most predictive

of malignancy in a pancreatic cyst. In malignant cysts, elevated CEA is

more predictive of histology than K-ras or LOH mutations. DNA

mutational analysis should be used selectively rather than routinely.

Costs are significant with DNA analysis. Confocal laser endomicroscopy

(CLE) is a novel technology for real time in vivo microscopic imaging

using a probe inserted through a 19-G needle. CLE findings of mucinous

tumors include finger-like papillae with layers of a thick band-like

epithelium. Serous cysts have a superficial network or fern-type

pattern, while pseudocysts contain bright particles. Cytology, CEA

levels and -K-ras mutation analyses are the most important in clinical

practice. Is important differentiate between benign and malignant

lesions to determine whether surgical resection or conservative

management is required. (See attached Table).

References:

References:

1- Bhutani MS, Gupta V, Guha S, Gheonea DI, Saftoiu A.

Pancreatic cyst fluid analysis--a review. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis.

20(2):175-80, 2011

2- Rockacy M, Khalid A. Update on pancreatic cyst fluid analysis. Ann Gastroenterol. 26(2):122-127, 2013

3- Talar-Wojnarowska R, Pazurek M, Durko L, et al: Pancreatic cyst

fluid analysis for differential diagnosis between benign and malignant

lesions. Oncol Lett. 5(2):613-616, 2013

4- Ngamruengphong S, Lennon AM. Analysis of Pancreatic Cyst Fluid. Surg Pathol Clin. 9(4):677-684, 2016

5- Li F, Malli A, Cruz-Monserrate Z, Conwell DL, Krishna SG. Confocal

endomicroscopy and cyst fluid molecular analysis: Comprehensive

evaluation of pancreatic cysts. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 10(1):1-9,

2018

6- Arner DM, Corning BE, Ahmed AM, et al: Molecular analysis of

pancreatic cyst fluid changes clinical management. Endosc Ultrasound.

7(1):29-33, 2018

PSU Volume 56 NO 03 MARCH 2021

Complicated Appendicitis: How much antibiotics?

Appendicitis is the most common acute surgical emergency in

children. Though medical management of appendicitis using parenteral

antibiotics has gained popularity, laparoscopic or open appendectomy is

still the standard of care. The basic tents of management of

appendicitis are: resuscitate children with systemic inflammatory

response syndrome, control the source of contamination, remove most of

the infected or necrotic material and administer antimicrobial agents

to eradicate residual pathogens. Appendicitis can be classified as

simple or complicated. Complicated appendicitis refers to histologic

changes in the appendix associated with either gangrene and/or

perforation. Perforated appendicitis occurs in approximately 25-30% of

children presenting with acute appendicitis. Traditionally, complicated

appendicitis is managed postoperatively with 7-14 days of antibiotics.

This long therapeutic regimen has been challenged periodically. The

main reasons for postoperative antibiotics after appendectomy in

complicated appendicitis is reducing the incidence of surgical

site (wound) infection and formation of intraabdominal fluid

collections (abscess). Excluding gangrenous appendicitis, wound and

intraabdominal infection rates for children with perforated

appendicitis are 4% and 8% respectively. With the standard use of

laparoscopy with smaller incisions for appendectomy the surgical site

infection rate has decreased considerably. All children undergoing

appendectomy should receive a preoperative dose of a broad-spectrum

antibiotics before surgery. Cases with simple appendicitis or normal

appendix do not need to receive postoperative antibiotics as

postoperative infectious complications are extremely rare in this group

after a single preoperative dose of antibiotics. Complicated

appendicitis can be managed with shorter course of three to 5 days of

postoperative antibiotics after adequate source control. This course

depends on the clinical response of the child. In synthesis, the

parameters utilized to evaluate the clinical response to postoperative

antibiotic therapy include: temperature, heart rate, WBC count, and

gastrointestinal dysfunction due to peritonitis. This means that until

fever subsides (T < 38.5 C), normal heart rate returns, WBC < 11

and resolution of ileus with oral intake is not achieved, the child

will need antimicrobial therapy. The STOP-IT trial found that outcomes

in patients with intraabdominal infections who undergo successful

source control procedure and received a fixed 4 days course of

antimicrobial therapy had similar results in outcome as patient whom

systemic antimicrobial agents were administered until after resolution

of signs and symptoms of sepsis. The occurrence of a postoperative

abscess is the single most important determinant of outcomes in

children with perforated appendicitis. Retained fecalith after

appendectomy are a source of continued and recurrent infection and

should be removed surgically. As we define better grades of perforation

during surgery, we will be able to correlate them with increased

postoperative abscess rate.

References:

1- Neilson IR, Laberge JM, Nguyen LT, et al: Appendicitis in Children:

Current Therapeutic Recommendations. J Pediatr Surg. 25(11): 1113-1116,

1990

2- Emil S, Laberge JM, Mikhail P, et al: Appendicitis in Children: A

ten-Year Update of Therapeutic Recommendations. J Pediatr Surg. 38(2):

236-242, 2003

3- Emil S, Taylor M, Ndiforchu F, Nguyen N: What are the True

Advantages of a Pediatric Appendicitis Clinical Pathway? Am Surg. 72

(10): 885-889, 2006

4- Sawyer RG, Claridge JA, Nathens AB, et al: Trial of Short-Course

Antimicrobial Therapy for Intraabdominal Infection. NEJM 372:

1996-2005, 2015

5- Emil S, Elkady S, Shbat L, et al: Determinants of postoperative

abscess occurrence and percutaneous drainage in children with

perforated appendicitis. Pediatr Surg Int. 30: 1265-71, 2014

6- Yousef Y, Youssef F, Homsy M, et al: Standardization of care for

pediatric perforated appendicitis improves outcomes. J Pediatr Surg 52:

1916-1920, 2017

7- Posillico SE, Young BT, Ladhani HA, Zosa BM, Claridge JA:

CurrentEvaluation of Antibiotic Usage in Complicated Intra-Abdominal

Infection after the STOP IT Trial: Did We STOP IT?. Surg Infect 20(3):

184-191, 2019

Intraoperative Cholangiogram

Cholelithiasis has increased in incidence in the pediatric

population, mostly the result of western diet and improve ability to

detect them using ultrasonography. Cholelithiasis can cause biliary

colicky pain, acute and chronic inflammation, pancreatitis and biliary

obstruction from gallstone impaction in the common bile duct

(choledocholithiasis). Hemolytic disorders account for 20% of children

with cholelithiasis. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is the gold

standard method for gallbladder removal in children and adults with

disease gallbladder. In children with gallstone pancreatitis,

biochemical jaundice, cholangitis or ultrasound evidence of bile duct

dilatation an MRCP should be performed to diagnosed choledocholithiasis

before embarking in removal of the gallbladder. Laparoscopic removal of

the gallbladder with bile duct obstruction could result in leakage of

the cystic duct stump or development of cholangitis. In the

laparoscopic era, ERCP with sphincterotomy is used either before LC for

suspected common bile duct (CBD) stones or after LC for missed CBD

stones, bile duct injuries or late strictures. Intraoperative

cholangiogram (IOC) is a technique in which a small catheter is passed

either through the cystic duct or infundibulum of the gallbladder,

contrast is injected and fluoroscopic films of the biliary tree are

obtained. IOC was first reported in the early 1990's. Previous

indications for IOC include findings of bile duct dilatation, defining

aberrant biliary tree anatomy, in cases of confused anatomy,

confounding biliary disorders (choledochal cysts, biliary atresia or

other congenital anomalies), and when bile duct injury is suspected

during cholecystectomy. In places where MRCP is not available, IOC is

useful to identify biliary anomalies or obstruction causing

choledocholithiasis, cholangitis, elevated liver enzymes or

pancreatitis. With time, IOC has gone from a routine procedure to a

selective procedure during removal of the gallbladder in children. IOC

adds time to the procedure potentially increasing costs, puts the

patient at risk of iatrogenic injury, adds radiation exposure to the

patient, and is no more sensitive than preoperative MRCP. Recent

nationwide database studies of cholecyctectomies in children have found

that:1) Routine IOC is more commonly employed in children with

cholecystitis and less commonly performed in patents with

cholelithiasis. 2) Cholecystectomy alone when compared against

cholecystectomy with routine IOC is associated with higher rates of

bile duct injury, perforation, laceration, sepsis and other infections.

3) These children are less likely to have readmission to the hospital

within 30 days and one year. 4) Patients who undergo routine IOC have

decreased hospital length of stay and decreased overall index hospital

costs. Other studies have found IOC and hospital operative volume are

not readily associated with decreased bile duct injury. Increase use of

IOC or tendency is associated with increased risk for bile duct injury.

The use of IOC is associated with surgeons' preference and training as

there is no clear evidence to guide routine

utilization.

References:

1- Lugo-Vicente HL: Trends in Management of Gallbladder Disorders in Children. Pediatr Surg Int. 12(5-6): 348-352, 1998

2- Waldhausen JH, Graham DD, Tapper D: Routine intraoperative

cholangiography during laparoscopic cholecystectomy minimizes

unnecessary endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in children.

J Pediatr Surg. 36(6):881-4, 2001

3- Mah D, Wales P, Njere I, et al: Management of suspected common bile

duct stones in children: role of selective intraoperative cholangiogram

and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. J Pediatr Surg.

39(6):808-12, 2004

4- Hamad MA, Nada AA, Abdel-Atty MY, Kawashti AS: Major biliary

complications in 2,714 cases of laparoscopic cholecystectomy without

intraoperative cholangiography: a multicenter retrospective study. Surg

Endosc. 25(12):3747-51, 2011

5- Kelley-Quon LI, Dokey A, Jen HC, Shew SB: Complications of pediatric

cholecystectomy: impact from hospital experience and use of

cholangiography. J Am Coll Surg. 218(1):73-81, 2014

6- Martin B, Ong EGP: Selective intraoperative cholangiography during

laparoscopic cholecystectomy in children is justified. J Pediatr Surg.

53(2):270-273, 2018

7- Quiroz HJ, Valencia SF, Willobee BA, et al: Utility of routine

intraoperative cholangiogram during cholecystectomy in children: A

nationwide analysis of outcomes and readmissions. J Pediatr Surg.

56(1):61-65, 2021

Appendicitis during Covid19 Pandemic

Acute appendicitis is the most common surgical emergency in

children. More than 70,000 appendectomies are performed in children

each year in the USA, approximately one-third of childhood admissions

for abdominal pain. Since the discovery of Sars-Cov2 coronavirus as the

cause of Covid19 disease early in 2020, a global pandemic developed

which continues to affect medical and surgical care of children and

adults. Children who develop Covid19 mostly suffer from a mild disease

process, only a minority presenting with respiratory distress syndrome

or multiorgan failure. With the pandemic the instructions to the

population were to stay home, avoid visiting local clinics and

hospitals while using more telemedicine-based practice. In many

institutions programmed or elective surgery was postponed. Parental

concerned with the possibility of contracting Covid19 in public places

such as clinics or emergency rooms couple with inadequate clinical

evaluation using telemedicine, and the inability to perform a full

physical examination led to a delayed diagnosis of appendicitis. This

resulted in an increase in development of complex appendicitis

(gangrenous and perforated) along with an increase in intraabdominal

complications such as perforation and peritonitis with

peri-appendicular abscess formation. An increased reliance on

outpatient care during a time when many clinics were not seeing

patients most likely contributed to delay in diagnosis. As hospital

systems were reaching capacity, a delay in presentation was created due

to the need for transfer from one health care center to another. A few

institutions changed to non-operative management of appendicitis in an

effort to conserve resources, minimized non-emergent surgical

procedures and allow for Covid19 testing to result. Non-operative

management with intravenous antibiotics can be applied to almost 50% of

children presenting with acute appendicitis. Children with persistent

pain, leukocytosis or an appendicolith in images were taken directly to

the operating room for laparoscopic appendectomy. The observed increase

in complicated appendicitis cases in children during 2020 is most

likely due to Covid19 pandemic. In other institutions the covid19

pandemic increased the number of children managed for acute

appendicitis during the lock down due to closure of general surgery

departments in proximity hospital resulting in an increase in referral

to children hospitals. Children managed for acute appendicitis were

older than historic controls and more commonly transferred from other

institutions. Nonoperative management of uncomplicated appendicitis in

children resulted in an increase in length of stay and readmission.

Ages at presentation correlated with increased severity of disease on

presentation and higher rates of perforation and intraabdominal abscess

formation, increased use of antibiotics, longer length of stay and

longer duration until symptoms resolution for children managed during

the pandemic. Children with appendicitis presented during the pandemic

with more advanced disease.

References:

1- Snapiri O, Rosenberg Danziger C, Krause I, et al: Delayed diagnosis

of paediatric appendicitis during the COVID-19 pandemic. Acta Paediatr.

109(8):1672-1676, 2020

2- Kvasnovsky CL, Shi Y, Rich BS, et al: Limiting hospital resources

for acute appendicitis in children: Lessons learned from the U.S.

epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Pediatr Surg. 2020 Jun

23:S0022-3468(20)30444-9. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2020.06.024.

3- Montalva L Haffreingue A, Ali L, et al: The role of a pediatric

tertiary care center in avoiding collateral damage for children with

acute appendicitis during the COVID-19 outbreak. Pediatr Surg Int.

36(12):1397-1405, 2020

4- Gerall CD, DeFazio JR, Kahan AM, et al: Delayed presentation and

sub-optimal outcomes of pediatric patients with acute appendicitis

during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Pediatr Surg. 2020 Oct

19:S0022-3468(20)30756-9. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2020.10.008.

5- La Pergola E, Sgro A, Rebosio F, et al:Appendicitis in Children in a

Large Italian COVID-19 Pandemic Area. Front Pediatr. 2020 Dec

9;8:600320. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.600320.

6- Place R, Lee J, Howell J: Rate of Pediatric Appendiceal Perforation

at a Children's Hospital During the COVID-19 Pandemic Compared With the

Previous Year. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Dec 1;3(12):e2027948.

doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.27948.

7- Tankel J, Keinan A, Blich O, et al: The Decreasing Incidence of

Acute Appendicitis During COVID-19: A Retrospective Multi-centre Study.

World J Surg. 44(8):2458-2463, 2020

PSU Volume 56 NO 04 APRIL 2021

Abdominal Wall Defects and Undescended Testis

The most common congenital abdominal wall defects (AWD) in

children affecting testicular descent include gastroschisis,

omphalocele and prune belly syndrome. Gastroschisis is more

common than omphalocele or prune belly syndrome. Undescended testes are

more common among AWD patients than the general population, with the

highest prevalence in omphalocele. Testicular descent is known to be

related to intraabdominal pressure and the gubernaculum. Without higher

pressures the forces that encourage testicle migration are absent.

Failure of appropriated abdominal pressure and/or sudden disruption of

the gubernaculum at the time of formation can lead to abdominal

undescended testes. Undescended testes are a concomitant birth anomaly

associated with abdominal wall defects in almost 20 to 40% of all males

patients. Undescended testes in children with abdominal wall defects

may be found within or outside the abdominal cavity. The majority of

undescended testes are found at the internal spermatic ring.

Gestational age and birth weight do not appear to be a significant

factor associated with testicular maldescent in several series. Closure

of the abdominal wall defect using either mesh or primary closure is

initially warranted. After closure of the abdominal wall defect and in

the ensuing next 12 months, more than half of all undescended testes

migrate to the appropriate position at follow-up requiring no

intervention. Migration of the testes into the scrotum in cases of

left-sided undescended testes born with gastroschisis, along with most

in omphalocele is less likely. Of the testes that do not spontaneously

descend into the scrotum, nearly half (43%) migrated into the inguinal

canal. In cases where the testes remained in the abdominal cavity

(non-palpable), laparoscopy is successfully performed to localize and

remove or reposition the testes. Early conservative management allows

normal spontaneous descent in most testes. Testes that are

extraabdominal at birth appear to be less likely to spontaneously

migrate into the scrotum compared with those that are intraabdominal at

birth. Extraabdominal testes seem to have a greater incidence of

atrophy and need for orchiectomy. Babies with prolapse testes out of

the abdominal cavity should undergo manual repositioning placing the

testis as near as possible to the internal spermatic ring. It is

important to record the position of the intraabdominal undescended

testes at the time of abdominal wall repair because future diagnostic

laparoscopy or exploration is likely to be difficult. The majority will

descend on their own without any need for surgical intervention.

Orchiopexy in a newborn with fragile testicular vessels and the risk of

compromised blood flow in the presence of temporarily raised

intracoelomic pressure after primary closure may jeopardize testicular

viability. Other authors believe that early mobilization and fixation

can improve the outcome of the undescended testis. Surgical

intervention for an undescended testis after closure of AWD is

challenging, characterized by adhesions and short gonadal vessels

necessitating staging the descent.

References:

1- Lawson A, de La Hunt MN: Gastroschisis and undescended testis. J Pediatr Surg. 36(2):366-7, 2001

2- Chowdhary SK, Lander AD, Buick RG, Corkery JJ, Gornall P: The

primary management of testicular maldescent in gastroschisis. Pediatr

Surg Int. 17(5-6):359-60, 2001

3- Hill SJ, Durham MM: Management of cryptorchidism and gastroschisis. J Pediatr Surg. 46(9):1798-803, 2011

4- Yardley IE, Bostock E, Jones MO, Turnock RR, Corbett HJ, Losty PD:

Congenital abdominal wall defects and testicular maldescent--a 10-year

single-center experience. J Pediatr Surg. 47(6):1118-22, 2012

5- Raitio A, Syvanen J, Tauriainen A, et al: Congenital abdominal wall

defects and cryptorchidism: a population-based study. Pediatr Surg Int.

2021 Jan 31. doi: 10.1007/s00383-021-04863-9.

6- Berger AP, Hager J: Management of neonates with large abdominal wall

defects and undescended testis. Urology. 68(1):175-8, 2006

Congenital Anal Stenosis

Congenital anal stenosis is a rare disorder classified as a

low anorectal malformation, mainly a short stenosis in most cases, but

sometimes the child has a funnel shape long stenosis associated with a

presacral mass, bony sacral defect, anterior meningocele or other

anomaly. The type of sacral dysplasia is scimitar and the presacral

tumor is a mature teratoma in most of the cases. Children with

congenital anal stenosis suffer from chronic intractable constipation,

soiling, encopresis and megarectosigmoid. Constipation is the most

common early functional problem in children with anal stenosis in more

than 40% of the cases. Recalcitrant constipation is more common in

children with a delayed diagnosis and treatment of anal stenosis.

Congenital anal stenosis (CAS) can also be associated with

Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome. On physical examination,

children with CAS have a stenotic opening at the normal anal site

barely admitting a small Hegar dilator. Palpable fecalomas can be found

upon abdominal examination. In this malformation, the anal canal is

usually located at least partially inside the voluntary sphincter

funnel. Occasionally the diagnosis of anal stenosis is delayed to later

infancy, especially in cases where the bowel outlet is stenotic but at

or near the proper anal position. Newborns with anal stenosis usually

pass meconium in the first 48 hours after birth. Children born with CAS

should undergo an active search for associated malformations including

echocardiogram, ultrasound of the spinal cord and kidneys,

cystourethrogram and imaging of the entire spine including the sacrum

(MRI). CAS can be managed with gradual Hegar dilatations usually

without the need for anesthesia. Serial dilatations are started with a

Hegar dilator that is easily fitted into the anal opening, usually with

a size between six and 8 mm. Dilatations are taught to parents to

continue management increasing to the next number on a weekly basis,

continued for six weeks after the age-appropriate size of the anus is

reached. Currarino syndrome, dysganglionosis including Hirschsprung's

disease and chromosomal defects commonly occurs in children with funnel

anus. The mortality of patients with low anomaly as CAS, is about three

times lower than that of patients with high anomalies, and usually

associated to cardiac defects. Long-term results of low malformations

are usually good in most patients. Poor results are usually associated

to neurological damage, mental retardation or insufficient care of

patients. In severe cases of anal stenosis, the posterior rectum is

mobilized in the form of rectal advancement, and the posterior 180

degrees is anastomosed directly to the skin with preservation of the

anal canal as the anterior final anoplasty. These patients have an

excellent prognosis for bowel control and fecal continence, and

therefore, complete mobilization and resection of the anal canal must

be avoided. Those children with CAS and stenosis involving only the

skin-level can be managed with a Heineke-Mikulicz anoplasty with very

good results.

References:

1- Suomalainen A, Wester T, Koivusalo A, Rintala RJ, Pakarinen MP:

Congenital funnel anus in children: associated anomalies, surgical

management and outcome. Pediatr Surg Int. 23(12):1167-70, 2007

2- Joshi M, Singh S, Vyas T, Chourishi V, Jain A:

Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome and anal canal stenosis: case

report and review of literature. J Pediatr Surg. 45(12):e29-31, 2010

3- Pakarinen MP, Rintala RJ: Management and outcome of low anorectal malformations. Pediatr Surg Int. 26(11):1057-63, 2010

4- Lane VA Wood RJ, Reck C, Skerritt C, Levitt MA: Rectal atresia and

anal stenosis: the difference in the operative technique for these two

distinct congenital anorectal malformations. Tech Coloproctol.

20(4):249-54, 2016

5- Halleran DR, Sanchez AV, Rentea RM, et al: Assessment of the

Heineke-Mikulicz anoplasty for skin level postoperative anal strictures

and congenital anal stenosis. J Pediatr Surg. 54(1):118-122, 2019

6- Brem H, Beaver BL, Colombani PM, et al: Neonatal diagnosis of a

presacral mass in the presence of congenital anal stenosis and partial

sacral agenesis. J Pediatr Surg. 24(10):1076-8, 1989

Appendix Duplication

The vermiform appendix is a tubular, narrow, worm-shaped

part of the alimentary canal that lies near the ileocecal junction and

communicates with the cecum. The appendix develops as a conical

extension from the apex of the cecal diverticulum which arises from the

antimesenteric border of the proximal part of the post arterial segment

of the midgut. Anomalies associated with the appendix are rare.

Duplication of the vermiform appendix is very rare occurring with an

incidence of 0.0004% after appendectomy. Appendiceal duplication is

classified into three types (Cave-Wallbridge classification). Type A

consists of various degrees of partial duplication on a normally

localized appendix with a single cecum. Type B consists of a single

cecum with two completely separate appendixes. This type is further

subdivided into a B1, bird-like type if the two appendixes are located

symmetrical on either side of the cecum as usually occurs in birds, and

B2 also known as tenia-coli type which has a normally located appendix

arising from the cecum at the usual site and a second separate

rudimentary appendix located along the line of one of the tenias. B1 or

bird-like type of duplication is the most common type of appendiceal

duplication (37%). Type B2 duplication can be mimicked by a solitary

inflamed diverticulum found on the cecum, usually at the medial border

just above the ileocecal junction. B3 if the second appendix is located

along the tenia of the hepatic flexure of the colon, and B4 if the

location of the second appendix is along the tenia of the splenic

flexure of the colon. Type C consists of a duplicated cecum, each with

an appendix. A horseshoe configuration of duplication and triple

appendices have also been described. Appendiceal duplication is most

commonly identified incidentally during surgery or at autopsies. The

most common presentation is appendicitis with the duplication being

discovered intraoperatively. Median age at presentation of these

patients is adolescent years, males and females affected equally.

CT-Scan is the best mode of imaging to identify a duplicated

appendix. Besides inflammation, appendiceal duplication can

present with recurrent intussusception or an appendiceal mass. Surgeons

have to be aware of such anomalies since a second laparotomy revealing

a previously removed appendix can cause medicolegal situations. In

cases with appendiceal duplication, when only one appendix is inflamed,

both should be removed to avoid a diagnostic dilemma that may arise

later.

References:

1- Varshney M, Shahid M, Maheshwari V, Mubeen A, Gaur K: Duplication of

appendix: an accidental finding. BMJ Case Rep. 2011 Mar

8;2011:bcr0120113679. doi: 10.1136/bcr.01.2011.3679.

2- Marshall AP, Issar NM, Blakely ML: Aapendiceal duplication in

children presenting as a appendiceal tumor and as recurrent

intussusception. J Pediatr Surg. 48: E9-E12, 2013

3- Dubhashi SP, Dubhashi UP, Kumar H, Patil C: Double Appendix. Indian J Surg. 77(Suppl 3):1389-90, 2015

4- Bhat GA, Reshi TA, Rashid A: Duplication of Vermiform Appendix. Indian J Surg. 78(1):63-4, 2016

5- Nageswaran H, Khan U, Hill F, Maw A: Appendiceal Duplication: A

Comprehensive Review of Published Cases and Clinical Recommendations.

World J Surg. 42(2):574-581, 2018

6- Chew DK, Borromeo JR, Gabriel YA, Holgersen LO: Duplication of the vermiform appendix. J Pediatr Surg. 35(4):617-8, 2000

PSU Volume 56 No 05 MAY 2021

Eosinophilic Cholecystitis

Eosinophilic cholecystitis is described as acute acalculous

cholecystitis associated with infiltrations of eosinophils into the

gallbladder wall. Acalculous cholecystitis is a rare condition in

children. It occurs during the course of infectious disease, as well as

in children on total parenteral nutrition, after surgery, trauma and

extensive burns. The etiology of acalculous cholecystitis includes

decreased blood flow to the gallbladder, biliary tract obstruction and

hyperconcentration of the bile. The disease can progress to necrosis or

perforation of the gallbladder. Eosinophilic cholecystitis (EC) is very

rare, reported in 0.5-6.5% of removed gallbladders. The etiology of

eosinophilic cholecystitis is unknown and probably represents a

hypersensitivity type of inflammatory response to altered bile.

Histologic findings diagnostic of eosinophilic cholecystitis includes

transmural infiltration of leukocytes with more than 90% eosinophils

present. Known causes of eosinophilic cholecystitis include parasitic

infestation (clonorchis sinensis, echinococcus and Ascaris

lumbricoides), gallstones, allergies, reaction to certain medications

(erythromycin, L-tryptophan and cephalosporins), allergic granulomatous

vasculitis, and association with eosinophilic gastroenteritis and/or

eosinophilic pancreatitis. Gallstones can be found in almost 90% of the

eosinophilic cholecystitis cases. Eosinophilic cholecystitis is more

common in adult females between the ages of 25-64 years. In children,

most cases occur during teenage years, though patient as young as seven

years of age has been reported. Symptoms of eosinophilic cholecystitis

resembles those of acute cholecystitis, including pain in the upper

right quadrant, fever, jaundice, Murphy positive sign, altered mental

status, shock, leukocytosis and postprandial nausea and vomiting.

Eosinophilic cholecystitis can be diagnosed only on resection of the

gallbladder and histologic examination. The diagnosis can be suspected

if there is evidence of peripheral eosinophilia which occurs in 10-15%

of cases. Ultrasound of the abdomen shows features of calculus

cholecystitis with pericholecystic fluid collection and edema,

thickened gallbladder wall and dilated common bile duct. The treatment

of choice of eosinophilic cholecystitis is removal of the sick

gallbladder. Cases associated with eosinophilic gastroenteritis or

cholangitis, can benefit from steroids medication as adjuvant therapy.

Eosinophilic cholecystitis usually show a good prognosis and patients

with cholecystitis alone improve after cholecystectomy.

References:

1- Muta Y, Odaka A, Inoue S, Komagome M, Beck Y, Tamura M, Arai E:

Acute acalculous cholecystitis with eosinophilic infiltration. Pediatr

Int. 57(4):788-91, 2015

2- Khan S, Hassan MJ, Jairajpuri ZS, Jetley S, Husain M.

Clinicopathological Study of Eosinophilic Cholecystitis: Five Year

Single Institution Experience. J Clin Diagn Res. 11(8):EC20-EC23, 2017

3- Gutierrez-Moreno LI, Trejo-Avila ME, Diaz-Flores A, et al:

Eosinophilic cholecystitis: a retrospective study spanning a

fourteen-year period. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 83(4):405-409, 2018

4- Keyal NK, Adhikari P, Baskota BD, Rai U, Thakur A: Eosinophilic

Cholecystitis presenting with Common Bile Duct Sludge and Cholangitis:

A Case Report.J Nepal Med Assoc 58(223): 188-91, 2020

5- Ito H, Mishima Y, Cho T, et al: Eosinophilic Cholecystitis

Associated with Eosinophilic Granulomatosis with Polyangiitis. Case Rep

Gastroenterol. 14(3):668-674, 2020

6- Garzon G LN, Jaramillo B LE, Valero H JJ, Quintero C EM:

Eosinophilic cholecystitis in children: Case series. J Pediatr

Surg. 56(3):550-552, 2021

Ovarian Harvest

With the advent of newer therapeutic options and increase in

intensity of such therapy more than 80% of children diagnosed with

cancer will be long-term survivors. During management for cancer

children will suffer long-term adverse effects such as loss of

fertility. Treatment protocols highly deleterious for ovarian function

include high dose alkylating agents (cyclophosphamide and busulfan),

total body irradiation and abdominopelvic irradiation (5-20 Greys) that

includes both ovaries. Ovarian damage is drug- and dose-dependent and

increases with age at treatment. For prepubertal females, ovarian

harvest using tissue cryopreservation is currently the only available

means of potentially preserving gonad function and fertility. Ovarian

tissue harvesting can take place immediately before intensive

chemotherapy or irradiation. Ovarian tissue is collected during the

removal of a primary abdominal tumor, or by means of a small suprapubic

laparotomy or laparoscopy. A single ovary or 2/3 of each ovary is

removed for cryopreservation. Most cases of major bleeding requiring

transfusion or re-operation are associated with partial oophorectomy.

Since the ovary can be different in the number of follicles present,

some people prefer specimen collection from both ovaries. During the

surgical procedure it is also possible to move residual gonads in order

to reduce effects of local therapy (ovarian transposition). The

preserved ovary is frozen down to liquid nitrogen temperature. Using a

biopsy of the cortex of the removed ovary the number of primordial and

primary follicles per square mm is determined. Also, in all malignant

cases small samples of gonadal tissue are also sent for routine

pathological assessment to rule out any gonadal involvement by the

primary cancer. Ovarian tissue is preserved until the child recovers

and it is reimplanted. Primordial follicles can be isolated from

cryopreserved ovarian tissue and grown to maturity in vitro to be

utilized for in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Orthotropic

sites of reimplantation are the residual ovary or a peritoneal pocket

in the ovarian fossa that permit a spontaneous pregnancy which is not

recommended in case of pelvic irradiation. Heterotrophic sites are the

subcutaneous forearm or abdominal tissue. Ovarian tissue transplant,

whether orthotopic or heterotopic, would allow for ovarian hormonal

production and restoration of a normal hormonal milieu allowing future

pregnancy. Orthotropic ovarian reimplantation has led to the birth of

more than 130 healthy babies. Mature oocyte and embryo cryopreservation

is an appropriate strategy for fertility preservation in postpubertal

females. Oocytes can be collected by transvaginal oocyte pick up, from

excised ovarian tissue or a combination of both procedures. However

this approach is time consuming with a low pregnancy rate and does not

replace ovarian tissue transplantation.

References:

1- Poirot CJ, Martelli H, Genestie C, et al: Feasibility of ovarian

tissue cryopreservation for prepubertal females with cancer. Pediatr

Blood Cancer. 49(1):74-8, 2007

2- Detti L, Martin DC, Williams LJ: Applicability of adult techniques

for ovarian preservation to childhood cancer patients. J Assist

Reprod Genet. 29(9):985-95, 2012

3- Babayev SN, Arslan E, Kogan S, Moy F, Oktay K: Evaluation of ovarian

and testicular tissue cryopreservation in children undergoing

gonadotoxic therapies. J Assist Reprod Genet. 30(1):3-9, 2013

4- Lima M, Gargano T, Fabbri R, Maffi M, Destro F: Ovarian tissue

collection for cryopreservation in pediatric age: laparoscopic

technical tips. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 27(2):95-7. 2014

5- Kedem A, Yerushalmi GM, Brengauz M, et al: Outcome of immature

oocytes collection of 119 cancer patients during ovarian tissue

harvesting for fertility preservation. J Assisted Reprod and Genetics.

35:851-856, 2018

6- Corkum KS, Rhee DS, Wafford QE, et al: Fertility and hormone

preservation and restoration for female children and adolescents

receiving gonadotoxic cancer treatments: A systematic review. J Pediatr

Surg. 54(11):2200-2209, 2019

7- Lukish JR: Laparoscopic assisted extracorporeal ovarian harvest: A

novel technique to optimize ovarian tissue for cryopreservation in

young females with cancer. J Pediatr Surg. 56(3):626-628, 2021

Minimally Invasive Follicular Thyroid Carcinoma

Papillary and follicular thyroid carcinomas are considered

the two differentiated carcinomas arising from follicular cells most

commonly found in children. Papillary thyroid carcinoma accounts for

more than 95% of all cases. Follicular thyroid carcinoma (FTC) accounts

for less than 5% of all cases, occur more commonly in females, and is

characterized by capsular and vascular invasion precluding making a

categorical diagnosis using fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy. FNA

biopsy usually describes a follicular tumor and the child undergoes

removal of the affected lobe with the tumor. FTC is known to be

associated with TSH elevation, iodine deficiency areas, hemiagenesis

and radiation exposure. Tumor size of pediatric FTC is significant

larger than in adult FTC. Histology of pediatric FTC is classified into

five patterns: microfollicular, follicular, solid/trabecular, oncocytic

and mixed patterns. Microfollicular pattern is the most common, while

solid/trabecular the most rare. In FTC, RAS mutation is the most common

genetic alteration with a prevalence in children of 12%. RAS mutation

is associated with smaller tumor size with a potential low risk

behavior in children. Follicular thyroid carcinoma can be further

divided into minimally invasive and widely invasive. Minimally invasive

FTC is diagnosed histologically when microscopic penetration of the

tumor capsule is found but there is no vascular invasion. Minimally

invasive FTC is difficult to diagnose prior to thyroidectomy unless

distant metastases to bone or lung and/or lymph nodes have been

detected and diagnosed by FNA or further imaging. Definitive diagnosis

is established after hemithyroidectomy. Minimally invasive FTC is an

encapsulated neoplasm characterized by unequivocal capsular invasion

with a relatively uneventful and indolent course. Minimally invasive

FTC carries an excellent prognosis with low risk of recurrence or

disease-specific mortality. Removal of the affected lobe and five-year

ultrasound-guided observation is sufficient therapy. Widely invasive

FTC is more aggressive, shows a widespread infiltration of blood

vessels into the adjacent thyroid parenchyma, displaying a poorer

prognosis than minimally invasive variant. Completion total

thyroidectomy as a second surgery and radioactive iodine ablation is

recommended for invasive FTC. Poor prognostic factors associated with

follicular thyroid carcinoma include older age, distant and neck

metastasis. Children with tumor exceeding 4 cm in length and associated

with vascular invasion carries a poorer

prognosis.

References:

1- Sugino K, Kameyama K, Ito K, et al: Outcomes and prognostic factors

of 251 patients with minimally invasive follicular thyroid carcinoma.

Thyroid. 22(8):798-804, 2012

2- Ito Y, Miyauchi A, Tomoda C, Hirokawa M, Kobayashi K, Miya A:

Prognostic significance of patient age in minimally and widely invasive

follicular thyroid carcinoma: investigation of three age groups. Endocr

J. 61(3):265-71, 2014

3- Stenson G, Nilsson IL, Mu N, et al: Minimally invasive follicular

thyroid carcinomas: prognostic factors. Endocrine. 53(2):505-11, 2016

4- Zou CC(1), Zhao ZY, Liang L: Childhood minimally invasive follicular

carcinoma: clinical features and immunohistochemistry analysis. J

Paediatr Child Health. 46(4):166-70, 2010

5- Vuong HG, Kondo T, Oishi N, et al: Paediatric follicular thyroid

carcinoma - indolent cancer with low prevalence of RAS mutations and

absence of PAX8-PPARG fusion in a Japanese population. Histopathology.

71(5):760-768, 2017

6- Nicolson NG, Murtha TD, Dong W, et al: Comprehensive Genetic

Analysis of Follicular Thyroid Carcinoma Predicts Prognosis Independent

of Histology. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 103(7):2640-2650, 2018

PSU Volume 56 NO 06 JUNE 2021

Neurothekeoma

Soft tissue tumor lesions are uncommon in the pediatric age

group. They differ from adults counterpart in frequency, anatomical

site and prognosis. In children, a dermal nodule could represent a

fibrous tumor, histiocytic tumor, lymphocytic tumor, melanocytic tumor

or a tumor of neural origin. Neurothekeoma is a rare benign soft tissue

tumor with distinctive histological features commonly located on the

upper extremity or the head and neck region in children. Originally

thought to arise from peripheral nerve sheath, it has been postulated

that neurothekeomas are of fibrohistiocytic differentiation. Based on

histology, immunohistochemical findings and amount of myxoid matrix

present, three variants of neurothekeoma are described: 1) myxoid,

which is the most common variety, 2) cellular and 3) mixed type. The

classic myxoid type, is encapsulated, characterized by myxomatous

changes, less cellularity with well-circumscribed spindle cells in a

myxoid matrix associated with multinucleated giant cells. The cellular

type is not encapsulated, the cells are epithelioid with eosinophilic

cytoplasm and rare mitosis. Cellular neurothekeomas can be locally

invasive with perineural and vascular invasion, but no locoregional

metastasis. The mixed type of neurothekeoma has varied cellularity with

focal myxoid regions. Clinically, neurothekeomas are slow-growing

asymptomatic lesions, but may be accompanied by pain upon pressure.

Though commonly dermal, mucosa and submucosal lesions have also been

described. Neurothekeomas tend to affect females more often than males,

usually in the second and early third decades of life. Age at

presentation can be between 15 months and 84 years. The most common

location is the upper extremity, followed by the head and neck region,

and lower extremity. Neurothekeoma clinically presents as a

superficially located skin-colored, pink, red, or brown

well-circumscribed papule or nodule measuring less than 2 cm.

Management of neurothekeomas consists of complete surgical excision

with microscopic negative margins. Incomplete removal of the lesion

will lead to recurrence in approximately 15% of patients. There are

reports of multiple neurothekeomas presenting concurrently. It is

almost impossible to make the diagnosis of a neurothekeoma

preoperatively, unless the patient has suffered a previous excision of

such dermal tumor. As neurothekeomas are considered benign lesions, the

prognosis is excellent with very low recurrence rate following complete

surgical excision.

References:

1- Al-Buainain H, Pal K, El Shafie H, Mitra DK, Shawarby MA: Myxoid

neurothekeoma: a rare soft tissue tumor of hand in a 5 month old

infant. Indian J Dermatol. 54(1):59-61, 2009

2- Zenner K, Dahl J, Deutsch G, Rudzinski E, Bly R, Perkins JA:

Metastatic cellular neurothekeoma in childhood. Int J Pediatr

Otorhinolaryngol. 119:86-88, 2019

3- Murphrey M, Huy Nguyen A, White KP, Krol A, Bernert R, Yarbrough K:

Pediatric cellular neurothekeoma: Seven cases and systematic review of

the

literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 37(2):320-325, 2020

4- Massimo JA, Gasibe M, Massimo I, Damilano CP, De Matteo E,

Fiorentino J: Neurothekeoma: Report of two cases in children and review

of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 37(1):187-189, 2020

5- Pan HY, Tseng SH, Weng CC, Chen Y: Cellular neurothekeoma of the upper lip in an infant. Pediatr Neonatol. 55(1):71-4, 2014

6- Peñarrocha M, Bonet J, Minguez JM, Vera F: Nerve sheath

myxoma (neurothekeoma) in the tongue of a newborn. Oral Surg Oral Med

Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 90(1):74-7, 2000

Renal Medullary Carcinoma

Renal medullary carcinoma (RMC) is a rare and highly

aggressive neoplasm that affects African-American adolescents and young

adult occurring almost exclusively in children with sickle cell trait

or sickle cell hemoglobinopathy. Sickle cell trait is a risk factor for

several conditions including chronic kidney disease, RMC, venous

embolism and sudden death. Most patients present between the ages of 11

and 39 years, with males affected 2:1 ratio. Most common presenting

symptoms for renal medullary carcinoma are gross hematuria, flank

pain, weight loss and abdominal mass. RMC is characterized for early

and widespread metastases. RMC arises from the renal papilla or

calyceal epithelium triggered by chronic medullary hypoxia. Imaging of

RMC commonly identifies a mass, more often in the right-side kidney,

with an average size of 7 cm associated with satellite lesions and

intratumoral necrosis. The most common imaging appearance of RMC is a

poorly marginated, infiltrating mass abutting the pelvocaliceal system.

This tumor is typically associated with a pseudocapsule with

well-defined margins. Lung metastasis have an atypical imaging

appearance with the most common pattern being pulmonary lymphangitic

carcinomatosis and nodules with indistinct margins being more common

than nodules with distinct margins. Pathologically, RMS is an

infiltrative tumor extending from the renal pelvis. These tumors

comprise sheets of poorly differentiated cells commonly found to have a

reticular growth pattern and adenoid cystic component with an

infiltrate of neutrophils. Visualization of sickle red blood cells is

pathognomonic for RMC. Most RMC are associated with a loss of

SMARCB1/INI1 occurring through a chromosomal translocation or deletion

that results in loss of protein expression identifiable by

immunohistochemistry. The management of RMC is radical nephrectomy with

retroperitoneal lymph node dissection followed in most cases by

systemic chemotherapy. At the time of diagnosis 70% of patients have

local lymph node involvement with one site of metastatic disease and

30% have two sites of metastatic involvement, most commonly lymph node,

lung, liver or the contralateral kidney. Cytotoxic chemotherapy with

platinum-based regimens has demonstrated partial and complete responses

with clinical benefit in several case series. No evidence points

to the benefit of screening patients with sickle cell trait for RMC

because no feasible schedule and modality of screening would have an

increase chance of identifying presentation of disease at an early

stage. No effective measure exists for prevention of this type of renal

malignancy. RMC carries a dismal prognosis with less than 5% surviving

longer than 36 months.

References:

1- Beckermann KE, Sharma D, Chaturvedi S, et al: Renal Medullary

Carcinoma: Establishing Standards in Practice. J Oncol Pract.

13(7):414-421, 2017

2- Sandberg JK, Mullen EA, Cajaiba MM, et al: Imaging of renal

medullary carcinoma in children and young adults: a report from the

Children's Oncology Group. Pediatr Radiol. 47(12):1615-1621, 2017

3- Msaouel P, Hong AL, Mullen EA, et al: Updated Recommendations on the

Diagnosis, Management, and Clinical Trial Eligibility Criteria for

Patients With Renal Medullary Carcinoma. Clin Genitourin Cancer.

17(1):1-6, 2019

4- Elliott A, Bruner E: Renal Medullary Carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med.

143(12):1556-1561, 2019 5- Blas L, Roberti J, Petroni J, Reniero L,

Cicora F: Renal Medullary Carcinoma: a Report of the Current

Literature. Curr Urol Rep. 2019 Jan 17;20(1):4. doi:

10.1007/s11934-019-0865-9.

6- Holland P, Merrimen J, Pringle C, Wood LA: Renal medullary carcinoma

and its association with sickle cell trait: a case report and

literature review. Curr Oncol. 27(1):e53-e56, 2020

Epidermolysis Bullosa

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) is a spectrum of rare, inherited,

blistering bullous skin disorders primarily affecting the skin and

pharyngoesophageal mucosa. EB affects approximately two to 4 per

100,000 children each year in the USA. EB is caused by a mutation in

the genes that encode any of the structural components of keratinocytes

and dermoepithelial junction. The mutation causes changes in proteins

that are responsible for adhesions defects between cutaneous structures

leading to blister formation. Autoantibodies to collagen VII binding to

the anchoring fibril zone and inducing mucocutaneous blistering have

been found in the acquired form of the disease in adults. EB is

classified into four main groups according to location of skin

separation. The four groups include EB simplex (intraepidermal layer),

junctional (within the lamina lucida of the basement membrane),

dystrophic (below the basement membrane) and a mixed type referred as

Kindler syndrome (mixed skin cleavage pattern). EB can be localized or

systemic. Cutaneous findings include blisters, scars, pigmentation

changes, alopecia, absent or dystrophic nails and deformity of hands

and feet. Extracutaneous symptoms of EB might affect eyes, teeth, oral

mucosa, genitourinary, gastrointestinal, respiratory and

musculoskeletal. The diagnosis of EB can be made from a skin biopsy,

genetic mutational analysis or detecting autoantibodies bound to the

basement membrane zone and in the serum against collagen VII.

Gastrointestinal complications of EB include blistering and stenosis of

the esophagus causing dysphagia and weight loss, gastroesophageal

reflux disease, hiatal hernia, gastritis, protein losing enteropathy,

anal fissure, megacolon, inflammatory bowel disease and constipation.

Constipation is one of the most common clinical features of EB

occurring in 40-75% of cases. Constipation occurs when defecation is

painful due to perianal blisters and fissures leading to fecal

retention. Blister formation in the oral mucosa can cause scarring

resulting in microstomia and ankyloglossia which restrict food