PSU Volume 58 NO 01 JANUARY 2022

Completion Thyroidectomy

Thyroid nodules in children are managed based exclusively on

the results of fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy. Benign FNA results

can be observed depending on the size, complexity and symptomatology of

the thyroid nodule. FNA results with positive pathology for papillary

carcinoma is best managed with total thyroidectomy with central lymph

node dissection. With results of FNA reported as indeterminate,

suspicious, insufficient or a follicular neoplasm, removal of the

affected lobe (hemithyroidectomy) might be performed. During removal of

the affected lobe, the contralateral neck and remaining lobe should not

be explored or violated. In cases in which a hemithyroidectomy is

performed and the final pathology is reported as a well-differentiated

papillary or follicular thyroid cancer, a completion thyroidectomy is

performed. Completion thyroidectomy reduces locoregional recurrence,

distant metastasis as well as low-risk carcinoma. The overall need for

completion thyroidectomy in the era of FNA is generally less than 5-10%

after lobectomy. The current major indications for completion

thyroidectomy are: gross extrathyroidal extension on the ipsilateral

side, gross residual disease on the esophagus, recurrent laryngeal

nerve or the tracheal wall, major vascular or capsular invasion and

poorly differentiated carcinoma or aggressive Hurthle cell carcinoma.

Whenever a completion thyroidectomy is to be performed, the surgeon

should study the gland previously removed to determine the status of

the parathyroid glands that might be removed with the specimen. The

rates of both temporary and permanent hypoparathyroidism are

considerably higher in patients in whom the parathyroid glands were

removed with the specimen. At the tine of completion thyroidectomy when

there is already a parathyroid gland in the initial hemithyroidectomy

specimen, the surgeon must make every effort to identify and preserve

both parathyroid and in the event of a suspected devascularization, the

gland should be autotransplanted. Hemithyroidectomy followed by

completion thyroidectomy does not appear to be associated with an

increase operative risk of hypocalcemia or recurrent laryngeal nerve

injury. The lower rate of temporary hypoparathyroidism and hypocalcemia

seen in the completion thyroidectomy group can be attributed to the

fact that the interval between operations allowed for recovery of any

reversible injury caused at the initial hemithyroidectomy.

Devascularized parathyroid glands require approximately four weeks to

return to full function. Compared with total thyroidectomy, completion

thyroidectomy has been associated with similar rates of recurrent

laryngeal nerve injury and lower rates of hypoparathyroidism. After

performing completion thyroidectomy, serum thyroglobulin levels tend to

be an adequate prognostic follow-up marker. Beside the effectiveness of

radioactive iodine for ablation of the remaining normal tissue or

residual microscopic disease is enhanced after completion

thyroidectomy. Recurrent laryngeal and superior laryngeal nerve

monitoring during completion thyroidectomy is associated with a

decrease risk of injury. Completion thyroidectomy is a safe procedure

with acceptable morbidity in the hand of experience surgeons.

References:

1- Rafferty MA, Goldstein DP, Rotstein L, et al: Completion

thyroidectomy versus total thyroidectomy: is there a difference in

complication rates? An analysis of 350 patients. J Am Coll Surg.

205(4):602-7, 2007

2- Gulcelik MA, Dogan L, Guven EH, Akgul GG, Gulcelik NE: Completion

Thyroidectomy: Safer than Thought. Oncol Res Treat. 41(6):386-390, 2018

3- Nicholson KJ, Teng CY, McCoy KL, Carty SE, Yip L: Completion

thyroidectomy: A risky undertaking? Am J Surg. 218(4):695-699, 2019

4- Sena G, Gallo G, Innaro N, et al: Total thyroidectomy vs completion

thyroidectomy for thyroid nodules with indeterminate

cytology/follicular proliferation: a single-centre experience. BMC

Surg. 19(1):87, 2019

5- Shaha AR, Michael Tuttle R: Completion thyroidectomy-indications and complications. Eur J Surg Oncol. 45(7):1129-1131, 2019

6- Shaha AR, Patel KN, Michael Tuttle R: Completion thyroidectomy-Have

we made appropriate decisions? J Surg Oncol. 123(1):37-38, 2021

Hematocolpos after Cloacal Repair

In females the most common anorectal malformation is an

imperforate anus with a rectovestibular fistula, followed by

rectoperineal fistula and the cloacal anomaly. Cloacal repair entails

reconstruction of the urethra, vagina and rectum which end in a common

channel. The aim of vaginal reconstruction is to provide a cosmetically

satisfactory introitus, a conduit for normal menstruation and pain-free

penetrative intercourse. There is a strong association of gynecologic

anomalies (60%) associated with cloaca. A high rate of menstrual

obstruction (40%) at puberty is well described. In less complex

malformations such as rectovestibular and rectoperineal fistula a

vaginal septum is the most common associated finding and can be managed

most effectively during the initial repair of the rectum without trauma

to the hymen or introitus. Vaginoscopy allows evaluation of the vaginal

anatomy during infancy and puberty by documenting of vaginal

duplication with 2 hemivaginas, and a septum, documentation of the

septal length and total vaginal length. During vaginoscopy, perhaps at

colostomy closure or creation of an appendicostomy, documentation of

the presence of mucus at the outer part of the cervix can be evaluated.

Also cannulation of the distal fallopian tube with instillation of

saline can be performed to visualize the egress of saline from the

vagina and confirm patency of the Müllerian system. Hematocolpus

is a medical condition of blood retained in the proximal vagina due to

an outflow tract obstruction or blockage of menstrual flow. The most

common cause of hematocolpus in children without anorectal malformation

is an imperforate hymen. In cases of repaired cloaca a longitudinal or

transverse vaginal septum, congenital or acquired vaginal atresia or

severe vaginal stricture, uterus didelphys and septate uterus can cause

hematocolpus. Ovarian function is normal in girls with repaired cloaca

so pubertal and breast development occurs as expected. Thelarche

(breast development) occurs between 9-10 years of age with menstruation

occurring at 12-12.5 years of age. Confirmation of the patency of the

reproductive tract before menarche is important to avoid obstruction,

pain, and risk to reproductive organs with infertility. It is during

this time that repaired cloaca can be studied further to determine if

there could exist the possibility of menstrual flow tract obstruction

and development of hematometrocolpos by performing serial ultrasound

studies. Almost 20% of children born with cloaca develop amenorrhea due

to absence of or underdeveloped Müllerian structures. US

surveillance of the reproductive structures should begin 6-9 months

after thelarche and continue every 6 months through menarche. If an

obstruction to menstrual flow is detected by visualization of a

thickened endometrium with hematocolpos, medical intervention should be

initiated immediately to minimize adverse sequelae. Hormonal

suppression of menses and endometrial stimulation should be started if

there is menstrual flow obstruction to prevent continued accumulation

of blood. Surgery is usually necessary to establish an adequate outflow

tract either by resection of a vaginal septum, introitoplasty,

posterior vaginoplasty or vaginal replacement with bowel in cases of

absent vagina. Other gynecologic concern for pubertal females include

the development of adnexal cysts, hydrosalpinges, endometriosis and

chronic pelvic pain. Women who had a history of a cloacal anomaly

should be delivered by cesarean section.

References:

1- Breech L: Gynecologic concerns in patients with anorectal malformations. Seminars Pediatr Surg. 19: 139-145, 2010

2- Versteegh HP, Sutcliffe JR, Sloots EJ, Wijnen RMH, Blaauw Id:

Postoperative complications after reconstructive surgery for cloacal

malformations: a systematic review. Tech Coloproctol 19: 201-207, 2015

3- Breech L: Gynecologic concerns in patients with cloacal anomaly. Seminars Pediatr Surg. 25: 90-95, 2016

4- Vilanova-Sanchez A, Reck CA, McCracken KA, et al: Gynecologic

anatomic abnormalities following anorectal malformations repair. J

Pediatr Surg. 53: 698-703, 2018

5- Vilanova-Sanchez A, McCracken K, Halleran DR, et al: Obstetrical

Outcomes in Adult Patients Born with Complex Anorectal Malformations

and Cloacal Anomalies: A Literature Review. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol.

32: 7-14, 2019

6- Fanjul M, Lancharro A, Molina E, Cerda J: Gynecological anomalies in

patients with anorectal malformations. Pediatr Surg Int. 35: 967-970,

2019

Apple Peel Atresia

Jejunoileal atresias are classified as type I characterized

by a transluminal septum; type II involves a fibrous cord connecting

two blind ending pouches; type IIIA has a V-shaped mesenteric defect;

and type IV exhibits multiple atetric segments. The term Apple peel

atresia (or Type IIIB intestinal atresia), occurring in less than 10%

of all jejunoileal atresias, refers to the development of a high

jejunal atresia with discontinuity of the small bowel and a wide gap in

the mesentery. The distal segment of jejuno-ileum is shortened and

assumes a helical configuration around a retrograde perfusing vessel.

The appearance is similar to a Christmas tree, hence the synonym

Christmas tree deformity. An intrauterine vascular accident after

emergence of the middle colic artery to the affected proximal bowel

during late gestation has been accepted as the cause of apple-peel

atresia presenting with a wide spectrum of occlusions of one or more

branches of the superior mesenteric artery. The bowel distal to the

atresia is precariously supplied in a retrograde fashion by anastomotic

arcades from the ileocolic, right colic or inferior mesenteric artery.

Most of these children have less than half of the normal length of the

small bowel and a physiological short bowel. Apple peel atresia is

usually reported as an isolated malformation, but has also been related

to malrotation, situs inversus and polysplenia. Not all distal

apple-peel atresias are associated with a proximal bowel atresia since

a few scattered reports of a mesenteric defect associated with a

marginal artery may cause the coiling defect of the apple peel as the

bowel outgrows it blood supply causing problems of ischemia later in

life associated with mesenteric internal hernias. Also, not all

apple-peel atresia are from the proximal jejunum, since very few have

been described arising after a proximal duodenal atresia related to the

second portion of the duodenum with absence of the third and fourth

portions of duodenum and superior mesenteric artery. Infants born with

high jejunal atresia have considerable dilatation of the proximal

bowel, while the distal segment is small and collapsed. Anastomosis

between two discrepant bowel sizes can cause functional bowel

obstruction. The resulting peristalsis is incapable of producing an

adequate upstream pressure gradient. As alternative, an antimesenteric

reduction-tapering proximal jejunoplasty can be used to perform

anastomosis reducing the caliber of the proximal bowel to fit an almost

end to end anastomosis with the distal microbowel. Serial transverse

enteroplasty of the dilated proximal jejunal atresia can also be

performed to reduce the caliber while lengthening it appropriately

without significant loss of absorptive area. Apple-peel atresias

frequently have a high incidence of prematurity, short gut, multiple

atresias and associated anomalies which constitute potential prognostic

factors. Antenatal US may suggest the diagnosis of jejunoileal atresia

with the presence of dilated fluid-filled loops of bowel and

polyhydramnios. Surgery is the preferred mode of treatment for

jejunoileal atresias and the goal of treatment is to establish bowel

continuity while preserving as much bowel length as possible.

Postoperative complications associated with apple-peel atresia include

anastomotic dysfunction (most common), sepsis (from leak or TPN), short

bowel syndrome, necrotizing bowel, stenosis and even death. Survival is

above 90%.

References:

1- Llore N, Tomita S: Apple peel deformity of the small bowel without atresia in a congenital

mesenteric defect. J Pediatr Surg. 48(1):e9-11, 2013

2- Onofre LS, Maranhao RF, Martins EC, Fachin CG, Martins JL:

Apple-peel intestinal atresia: enteroplasty for intestinal lengthening

and primary anastomosis. J Pediatr Surg. 48(6):E5-7, 2013

3- Sasa RV, Ranko L, Snezana C, Lidija B, Djordje S: Duodenal atresia

with apple-peel configuration of the ileum and absent superior

mesenteric artery. BMC Pediatr. 16(1):150, 2016

4- Dao DT, Demehri FR, Barnewolt CE, Buchmiller TL: A new variant of type III jejunoileal atresia.

J Pediatr Surg. 54(6):1257-1260, 2019

5- Zhu H, Gao R, Alganabi M, et al: Long-term surgical outcomes of apple-peel atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 54(12):2503-2508, 2019

6- Mangray H, Ghimenton F, Aldous C: Jejuno-ileal atresia: its

characteristics and peculiarities concerning apple peel atresia,

focused on its treatment and outcomes as experienced in one of the

leading South African academic centres. Pediatr Surg Int. 36(2):201-207, 2020

7- Zvizdic Z, Popovic N, Milisic E, Mesic A, Vranic S: Apple-peel

jejunal atresia associated with multiple ileal atresias in a preterm

newborn: A rare congenital anomaly. J Paediatr Child Health.

56(11):1814-1816, 2020

PSU Volume 58 No 02 FEBRUARY 2022

Pectus Arcuatum

Anterior chest wall deformities are not rare. They consist

of pectus excavatum as the most frequent form of chest deformities, and

by protrusion deformities such as pectus arcuatum and carinatum. Pectus

arcuatum, also known as pouter pigeon chest, Currarino-Silverman

syndrome, chondro-manubrial deformity or type two pectus carinatum, is

a rare and complex congenital chest wall deformity whose main feature

is protrusion and early ossification of the sternal angle of Lewis

associated with bilateral deformity of the 2nd to 4th cartilages. It

may also be associated with a depressed lower sternum. It also

involves a wavelike deformity, a mixed form of excavatum and carinatum

features, either along a longitudinal or along a transverse axis. The

visual appearance of pectus arcuatum is formed by the costal cartilage

protrusion. In most cases pectus arcuatum is a cosmetic defect. Though

the diagnosis is established by physical exam, chest films and CT-Scan

with 3-D reconstruction are needed if repair of the sternal defect is

warranted. Imaging using thoracic CT scans and customized aided design

virtual simulation allows the surgeon to predetermine the specific

cutting angle for each patient and therefore design a cutting template

tailored to the individual deformity. The surgical repair of this

rare deformity requires a modified open Ravitch technique. Patients are

usually young adults without comorbidities and no special preparation

is needed. The basic steps in the surgical correction described by

Ravitch consist of bilateral parasternal and subperichondrial resection

of the deformed costal cartilages, detachment of the xiphoid process,

transverse wedge osteotomy at the upper edge of the sternal depression,

and bending of the sternum to straighten its course, securing the

corrected position of the sternum. Satisfactory overall results occur

in 98% of patients. The Ravitch technique has a risk of growth

limitation to the thoracic cage due to a wide resection of the rib

cartilages, the reason that the repair is not undertaken until the

child has acquired a rigid skeletal structure later in life. Pectus

arcuatum can be successfully corrected by Ravitch-type of

chondrosternoplasty. Due to necessity to resect cartilages, late

puberty or adulthood is preferred, since by that age the growth of ribs

have finished. Repair of pectus deformity in children that might need

future cardiac surgery has revealed that concomitant surgery is

contraindicated before adolescence because pectus deformities may

spontaneously disappear or recur after early sternal surgery.

Congenital heart defects are reported occasionally as well as

simultaneous Poland syndrome. Concomitant surgery of cardiac defects

and pectus deformity is a reliable strategy in adolescent and adults

offering long-term results. The modified Ravitch technique is more

adequate as it can be used in all types of deformities and in

concomitant surgery allowing optimal operative exposure during cardiac

procedures, easy postoperative reentry and resuscitation maneuvers if

needed.

References:

1- Hysi I, Vincentelli A, Juthier F, et al: Cardiac surgery and repair

of pectus deformities: When and how? Int J Cardiol. 194:83-6, 2015

2- Kara M, Gundogdu AG, Kadioglu SZ, Cayirci EC, Taskin N: The use of

sternal wedge osteotomy in pectus surgery: when is it necessary? Asian

Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 24(7):658-62, 2016

3- Kim SY, Park S, Kim ER, et al: A Case of Successful Surgical Repair for Pectus Arcuatum Using

Chondrosternoplasty. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 49(3):214-7, 2016

4- Leng S, Bici K, Facchini F, et al: Customized Cutting Template to

Assist Sternotomy in Pectus Arcuatum. Ann Thorac Surg.

107(4):1253-1258, 2019

5- Kuzmichev V, Ershova K, Adamyan R: Surgical correction of pectus arcuatum. J Vis Surg. 2:55, 2016

6- Emil S: Current Options for the Treatment of Pectus Carinatum: When

to Brace and When to Operate? Eur J Pediatr Surg. 28(4):347-354, 2018

Imposter Syndrome

Imposter syndrome refers to a feeling of self-doubt or

innate fear of being discovered as a fraud or non-deserving

professional, despite their demonstrated talent and achievements.

Imposter syndrome is characterized by a chronic sense of self-doubt

coupled with a constant worry of being discovered as a fraud. Imposter

syndrome is more prevalent in high achievers, women, and

under-represented racial, ethnic, and religious minorities. Impostor

syndrome is increasingly recognized as a condition between physicians

and physicians in training. Despite remarkable academic and

professional achievements affected individuals beliefs that they

were unintelligent. For affected individuals, imposter syndrome can

lead to burnout, psychological distress, emotional suffering, and

serious mental health disorders, including chronic dysphoric stress,

anxiety, depression, drug abuse and suicide. Most cases start early

during high school or college. The true incidence of imposter syndrome

is unknown in medical professionals. In the US, among medical students

the rate of imposter syndrome was 49% in women and 24% in men, and

among residents the rate was similar. The root cause of imposter

syndrome is not known, but it has been related to depression and

anxiety, which are both present among residents, with suicide being the

second most common cause of death among residents. Imposter syndrome

among general surgery residents is not only prevalent but severe with

76% of residents reporting either significant or severe imposter

syndrome. Neither sex nor age correlates with the presence of, or level

of, imposter syndrome in the general surgery resident population. It is

believed that imposter syndrome is an incidentally protective mechanism

encouraged by the hierarchical culture of surgical training by which

residents are encouraged to self-regulate their decision-making

process. By constantly downplaying their own accomplishments, those

suffering from imposter syndrome may sabotage their own career.

Institutions must address imposter syndrome by increasing the

visibility of the problem, providing access to mental health coaching,

and establishing supportive organization policies. Institutions and

residency programs should provide training for mentors to help them

recognize the negative consequence of the imposter syndrome. Medical

educators must recognize that it is not just the underperforming or

failing learners who struggle and require support, and medical culture

must create space for physicians to share their struggles. The

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires

residency programs to support residents well-being via

established policies and programs. Imposter syndrome has been linked to

burnout and suicide in residents and understanding how to combat it may

help improve resiliency in residents. Imposter syndrome has been linked

to resident burnout and discussing imposter syndrome is viewed as an

effective intervention to promote resident wellness and resiliency.

When creating wellness interventions, residency programs should

consider addressing imposter syndrome.

References:

1- Kimyon RS: Imposter Syndrome. AMA J Ethics 22(7): E628-629, 2020

2- Mullangi S, Jagsi R: Imposter Syndrome: Treat the Cause, Not the Symptom. JAMA. 322(5):403-404, 2019

3- Chrousos GP, Mentis AA: Imposter syndrome threatens diversity. Science. 367(6479):749-750, 2020

4- Baumann N, Faulk C, Vanderlan J, Chen J, Bhayani RK: Small-Group

Discussion Sessions on Imposter Syndrome. MedEdPORTAL. 16:11004, 2020

5- Bhama AR, Ritz EM, Anand RJ, et al: Imposter Syndrome in Surgical

Trainees: Clance Imposter Phenomenon Scale Assessment in General

Surgery Residents. J Am Coll Surg. 233(5):633-638, 2021

6- Gottlieb M, Chung A, Battaglioli N, Sebok-Syer SS, Kalantari A:

Impostor syndrome among physicians and physicians in training: A

scoping review. Med Educ. 54(2):116-124, 2020

Short Bowel Syndrome

Short bowel syndrome (SBS) refers to a compromised bowel

absorptive capacity due to severely reduced mucosal surface resulting

in diarrhea, water-electrolytes imbalances, and protein malnutrition.

SBS is the most common cause of intestinal failure in children. Most

underlying conditions that lead to major loss of intestine in neonates

have their origin in intrauterine life. SBS usually occurs after

extensive bowel resection, either congenital or acquired, such as that

associated with small bowel atresia, complex gastroschisis, midgut

volvulus and necrotizing enterocolitis. The most common acquired cause

of SBS is NEC with 30% in most reported series. Factors influencing

outcome in SBS include underlying diagnosis, type of segments

preserved, stoma vs primary anastomosis, presence of ileocecal valve

and the age of the child at the time of surgery. Massive

resection stimulates modification in thickness and length of the muscle

layer and villi crypts. Distension of the remaining bowel is the most

common consequence after massive resection. Massive jejunal resections

are better tolerated than significant ileal resections. Ileal

resections are associated with impaired resorption of Vitamin 12, bile

salts and fatty acids. Three anatomical subtypes of SBS: (1) small

bowel resection with anastomosis and intact colon; (2) small bowel

resection with partial colon resection; (3) small bowel resection with

high output jejunostomy. Type 1 has the best potential for adaptation,

while type 3 the least. With the advent of parenteral nutrition support

survival of SBS improved significantly. Management of SBS aims to

promote adaptation of the remnant bowel. Parenteral nutrition (PN)

provides nutrition while the bowel achieves intestinal autonomy. The

bowel should be use for feeding as much and early as possible to

stimulate adaptation. Oral feeding maintains sucking and swallowing

functions, promotes release of epidermal growth factor from salivary

glands and increases GI secretion of trophic factors. Breast feeding

should be encouraged. Long term PN leads to sepsis, cholestasis due to

liver failure and death. Key predictors of mortality in SBS include

cholestasis (conjugated bilirubin > 2.5 mg%) and percentage of small

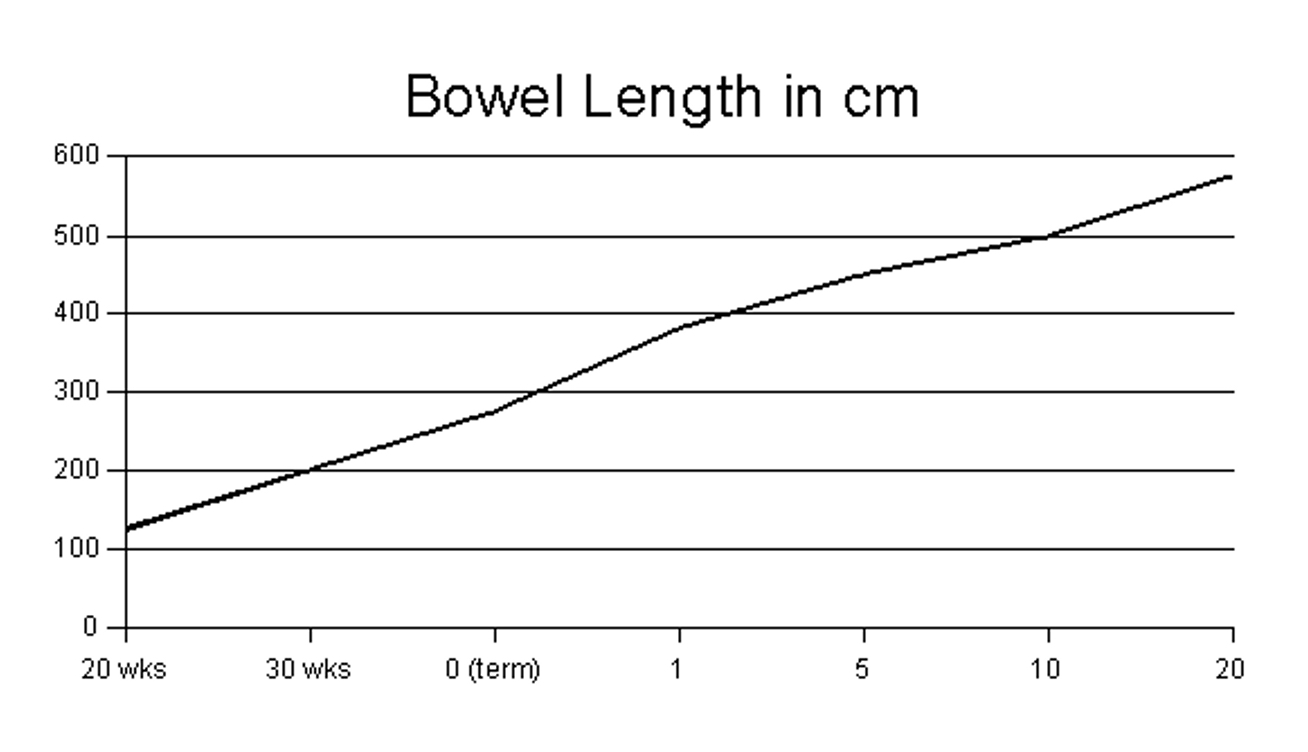

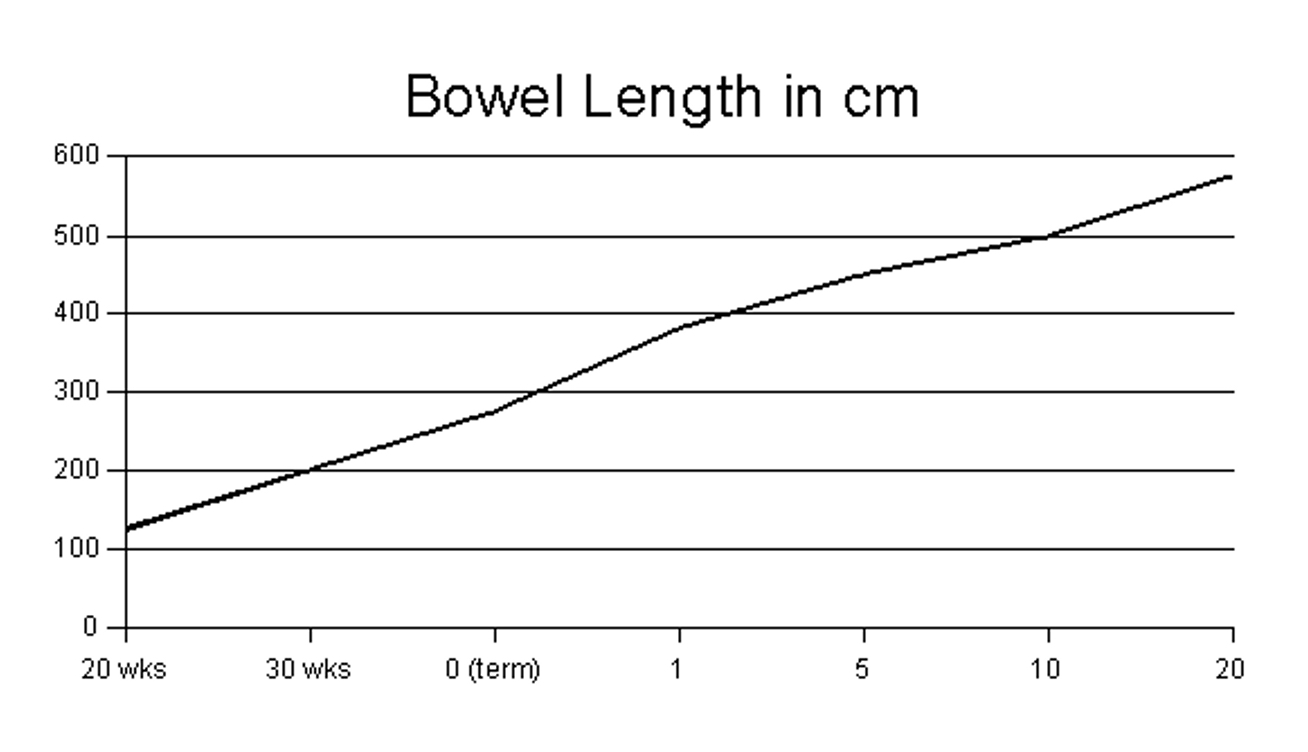

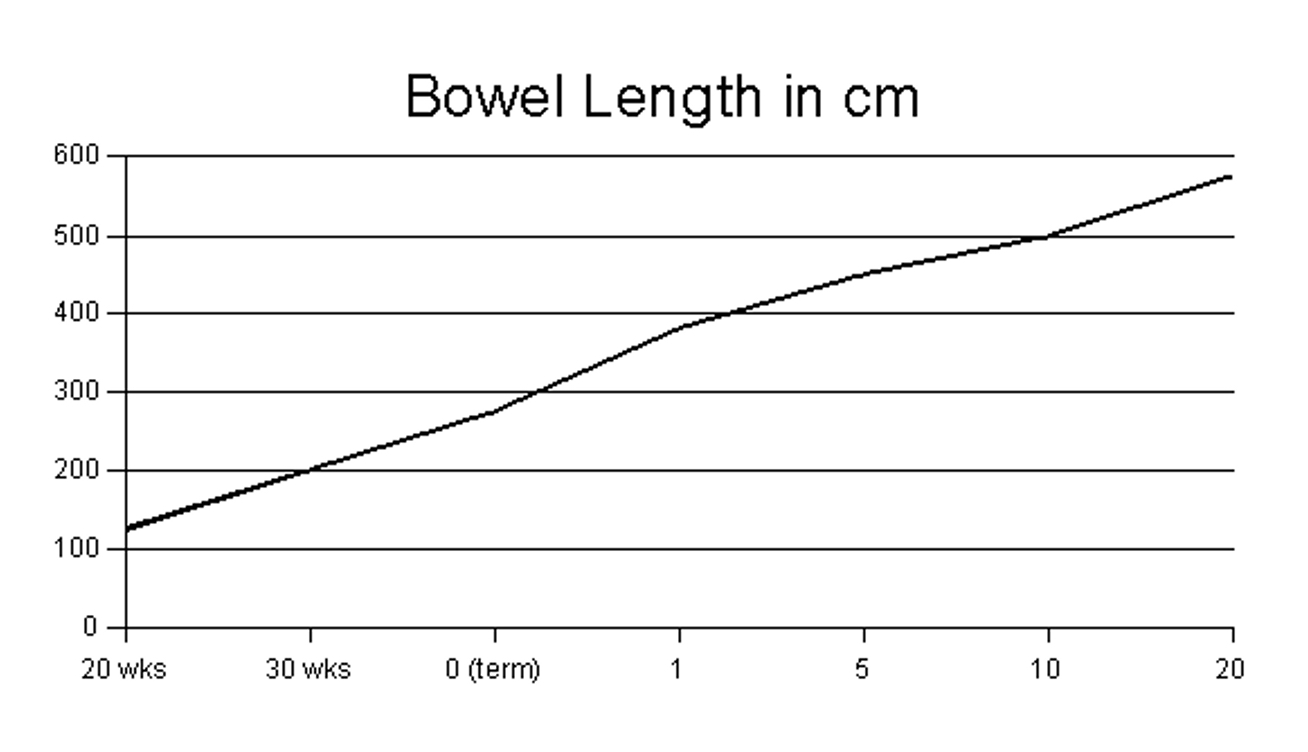

bowel length. A small bowel length greater than 10% of expected for a

given gestational age is highly predictive of survival (see normal

bowel length in accordance with gestational age graph). Presence of an

ileocecal valve and percentage of small bowel length are primary

predictors of weaning PN. Surgical approaches to maximize bowel

digestive and absorptive function are important in the management of

SBS. These include stoma closure, bowel continuity restoration,

resection of strictures and closure of fistula. When the bowel is

short, dilated, and static children might benefit from longitudinal

intestinal lengthening and tapering (Bianchi) or serial transverse

enteroplasty (STEP) procedures. The UGIS provide accurate estimates of

bowel diameter and length use to operative planning. Surgical bowel

lengthening should be considered in any chronically PN-dependent child

when there is substantial bowel dilatation and symptoms of small

intestinal bacterial overgrowth regardless of remaining bowel length.

Medical approach to SBS include antidiarrhea/ antimotility agents and

controlling acid/base balance. Hypersecretion of gastrin and gastric

acid occurs in children after extensive small bowel resection which

should be managed. Octreotide inhibits gastrin and diarrhea prolonging

transit time. Intestinal bacterial overgrowth frequently seen in SBS is

managed with probiotic and antibiotic therapy. Promising hormonal

therapy include glucagon-like peptide 2 hormone (Teduglutide) produced

by the L-cells of the terminal ileum. Teduglutide has a trophic effect

on the bowel, promotes absorption and adaptation. The future of SBS

might lie in an artificial grown and engineered harvested intestine.

Micronutrient deficiencies are frequent during intestinal

rehabilitation for SBS. The most common micronutrient deficiency

include zinc, copper, vitamin D and phosphorus after the transition to

enteral nutrition. With liver failure and reduced venous access, bowel

transplantation becomes the treatment of choice.

References:

1- Goulet O, Finkel Y, Kolacek S, Puntis J: Chapter 5.2.1. Short Bowel

Syndrome: Half a Century of Progress. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 66

Suppl 1:S71-S76, 2018

2- Spencer AU, Neaga A, West B, et al: Pediatric short bowel syndrome:

redefining predictors of success. Ann Surg. 242(3):403-9, 2005

3- Coletta R, Khalil BA, Morabito A: Short bowel syndrome in children:

surgical and medical perspectives. Semin Pediatr Surg. 23(5):291-7, 2014

4- Mutanen A, Wales PW: Etiology and prognosis of pediatric short bowel syndrome. Semin Pediatr Surg. 27(4):209-217, 2018

5- Hill S, Carter BA, Cohran V, et al: Safety Findings in Pediatric

Patients During Long-Term Treatment With Teduglutide for Short-Bowel

Syndrome-Associated Intestinal Failure: Pooled Analysis of 4 Clinical

Studies. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 45(7):1456-1465, 2021

6- Hollwarth ME: Surgical strategies in short bowel syndrome. Pediatr Surg Int. 2017 33(4):413-419, 2017

7- Feng H, Zhang T, Yan W, et al: Micronutrient deficiencies in

pediatric short bowel syndrome: a 10-year review from an intestinal

rehabilitation center in China. Pediatr Surg Int. 36(12):1481-1487, 2020

PSU Volume 58 No 03 MARCH 2022

Extremity Compartment Syndrome

Extremity compartment syndrome (ECS) in children is a

potential cause of permanent disability. Sustained increased pressure

in the limb fascial compartments compromises circulation causing

ischemia and necrosis of the contents within. Early recognition is

critical in avoiding further disability. Diagnosis of compartment

syndrome in children can be challenging due to poor cooperation,

difficulty with communication and difficulty measuring compartment

pressures of the affected limb in the conscious child. The most common

risk factors for ECS in the pediatric age comprise tibial diaphysis

fractures, soft-tissue injury, distal radius fracture, radius and ulna

diaphysis fracture and crush injury. Extremity fractures causes most

ECS in children (75%) followed by vascular injury, tibial osteotomy,

and soft-tissue injury. ECS can also arise from extrinsic causes that

exert pressure such as compressive casts or bandages, pneumatic

antishock garments, or intrinsic factors that increase the volume

inside the fascial envelops such as septic arthritis, intraosseous

infusions, toxic venom, burns, intramuscular hematomas, hereditary

bleeding disorders and viral diseases. An open fracture of the forearm

or leg significantly increases the risk for ECS. Nontraumatic causes of

limb compartment syndrome in children include ischemia-reperfusion

events after arterial injury, thrombosis, burns, bleeding disorders and

blunt injury. The pathogenesis of ECS is tissue damage leading to

increased intracompartmental pressure way above the closing pressure of

venules. Continued arterial inflow increases the pressure until the

arterioles develop stasis and ischemia occurs. Prolonged ischemia

beyond a six-hours period results in ischemic muscle which may result

in myonecrosis, chronic contracture and permanent nerve damage.

Compartment syndrome is a clinical diagnosis. The affected patient

develops paresthesia, numbness, swelling and pain out of proportion or

with passive movement of the extremity. Diminished pulses, pallor and

progressive neurologic deficit are late findings less commonly seen.

Pain is one of the earliest symptoms of ECS. Sensory deficit occurs

before motor dysfunction. Paresthesia in the affected extremity is one

of the first signs of hypoxia to nerve tissue within a compartment.

Blood flow in the capillary circulation ceases when compartment

pressure exceeds 35 mm Hg. The sensory nerves are affected first,

followed by the motor nerves and muscle, fat and skin become involved

later. ECS can be confirmed by the measurement of tissue compartment

pressure greater than 30 mm of Hg. The normal pressure in a muscle

compartment is less than 10-12 mm Hg. This diagnostic method is

essential in uncooperative, altered mental status, very young or

children with inconsistent clinical symptoms. Measurement of

compartment pressure can be performed using a slit catheter, wick

catheter, needle manometer, electronic arterial pressure transducer, or

a solid-state transducer intra compartment catheter. Management of

symptomatic ECS with pressures above 30 mm Hg is urgent decompressive

fasciotomy. Favorable outcomes are found in children who had a

fasciotomy less than six hours from the time of diagnosis. After

fasciotomy, limb compartment pressures should be monitored as

progressive muscle swelling may continue as a result of toxic effects

of infection. The lower leg is the most common location of acute ECS

with the anterior and lateral compartments most frequently affected.

Children tolerate increased intracompartmental pressure for longer

periods of time than adults before tissue necrosis becomes

irreversible. The most common complications after ECS in children is an

unpleasant scar since wound closure after upper or lower extremity

fasciotomies require split thickness skin graft. Silent compartment

syndrome is defined as confirmed compartment syndrome without

significant pain or absence of marked pain on passive motion. Pediatric

patients generally achieve good outcomes even when presenting in a

delayed fashion and undergoing fasciotomies after 24 hours of the

initial event. Decompressive fasciotomy is recommended even if there is

prolonged time from injury to diagnosis.

References:

1- Grottkau BE, Epps HR, Di Scala C: Compartment syndrome in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Surg. 40(4):678-82, 2005

2- Kanj WW, Gunderson MA, Carrigan RB, Sankar WN: Acute compartment

syndrome of the upper extremity in children: diagnosis, management, and

outcomes. J Child Orthop. 7(3):225-33, 2013

3- von Keudell AG, Weaver MJ, Appleton PT, et al: Diagnosis and

treatment of acute extremity compartment syndrome. Lancet.

386(10000):1299-1310, 2015

4- Shirley ED, Mai V, Neal KM, Kiebzak GM: Wound closure expectations

after fasciotomy for paediatric compartment syndrome. J Child

Orthop. 12(1):9-14, 2018

5- Frei B, Sommer-Joergensen V, Holland-Cunz S, Mayr J: Acute

compartment syndrome in children; beware of "silent" compartment

syndrome: A CARE-compliant case report. Medicine (Baltimore).

99(23):e20504, 2020

6- Lin JS, Samora JB: Pediatric acute compartment syndrome: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr Orthop B. 29(1):90-96,

2020

Diverticulitis in Children

The most common diverticulum in children causing surgical

problems is the Meckel's diverticulum. In very rare occasion the

pediatric patient can develop diverticular disease of the colon similar

to that occurring in the adult. Such diverticular disease can lead to

colonic diverticulitis. Diverticulitis is predominantly a disease of

adults older than 50 years of age, being extremely rare in children.

Low quantity dietary fiber, obesity, constipation, decreased physical

activity, steroids, and smoking all predispose individuals to

diverticulosis. Chronic increase intraluminal pressure leads to

formation of pseudo-diverticular outpouching. Less than 5% of all

patients with diverticula of any etiology develop diverticulitis. The

prevalence in the population younger than 40 is only 10%. No matter the

age group or etiology, diverticula can develop anywhere along the colon

from the cecum and appendix to the sigmoid colon. When diverticular

disease occurs in children, they are associated with alterations in the

component of the colonic wall. Some genetic disorders in children are

associated with diverticulitis due to weakening of the colonic wall by

alteration of collagen or elastin synthesis within the tissues. They

include cystic fibrosis, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan syndrome and

William-Beuren syndrome. Possible complications of colonic

diverticulosis include bleeding, inflammation (diverticulitis), and

perforation. Symptoms depend on localization of the diverticula.

Differential diagnosis includes colon cancer, Crohn's disease, ischemic

colitis, pseudomembranous enterocolitis, and pelvic inflammatory

disease. CT-Scan or MRI is utilized to diagnose diverticulitis.

Ultrasound and MRI can be useful alternatives in the initial evaluation

of a patient with suspected acute diverticulitis when CT imaging is not

available or is contraindicated. Pediatric colonic diverticulitis is

often associated with a more complicated course than that seen in

adults patients. Most pediatric cases have been described in the

cecum or ascending colon as a true diverticulum. Right sided

diverticulitis is relatively rare inflammatory condition affecting the

cecum and ascending colon. The incidence in children has not been

determined since most cases are incorporated into adult series. They

may be found as solitary lesion, multiple lesions, or parts of

generalized diverticulosis of the colon. Right colonic diverticula are

predominantly congenital and solitary being true diverticula consisting

of all layers of the bowel wall. Most children complain of right lower

quadrant pain with tenderness associated with nausea and vomiting.

Since they can mimic appendicitis, the diagnosis is often difficult.

Nonoperative management with antibiotics and bowel rest is advocated by

most, leaving resection or diverticulectomy for recurrent episodes,

obstructing mass, abscess, fistula, or perforation. The recurrence rate

of children managed successfully with intravenous antibiotics is 18%.

Classic findings related to sigmoid diverticulitis in adults include

left lower quadrant pain, fever, and leukocytosis. Complicated

diverticulitis is defined as diverticulitis associated with

uncontained, free perforation with systemic inflammatory response,

fistula, abscess, stricture, or obstruction. Micro-perforation in the

absence of a systemic inflammatory response is not considered

complicated diverticulitis. Symptomatic uncomplicated disease is

defined as diverticulosis with associated chronic abdominal pain in the

absence of clinically overt colitis. CRP above 150 mg/L is associated

with complicated diverticulitis. Elevated procalcitonin is associated

with diverticulitis recurrence. Most cases resolved with

antibiotics. Patients with recurrent symptoms, diverticular abscess,

fistula, obstruction, or stricture will need surgery. An elective

resection based on young age at presentation is not recommended.

Management of pediatric patients with diverticulitis should be

multidisciplinary, including GI, surgery, genetics, cardiology, and

ophthalmology.

References:

1- Santin BJ, Prasad V, Caniano DA: Colonic diverticulitis in

adolescents: an index case and associated syndromes. Pediatr Surg Int.

25(10):901-5, 2009

2- Ignacio RC Jr, Klapheke WP, Stephen T, Bond S: Diverticulitis in a

child with Williams syndrome: a case report and review of the

literature. J Pediatr Surg. 47(9):E33-5, 2012

3- Yano K, Muraji T, Hijikuro K, Shigeta K, Ieiri S: Cecal diverticulitis: Two pediatric cases. Pediatr Int. 61(9):931-933, 2019

4- Hall J, Hardiman K, Lee S, et al: The American Society of Colon and

Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of

Left-Sided Colonic Diverticulitis. Dis Coln Rectum 63: 728-747, 2020

5- Cadiz EM, Doan S, Kruszewski P: An Unusual Case of Diverticulitis in

a Teenager With a Complicated Clinical Course. J Pediatr Gastroenterol

Nutr. 71(5):e142, 2020

6- Lee ZW, Albright EA, Brown BP, Markel TA: Congenital cecal

diverticulitis in a pediatric patient. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep. 2021

Sep;72:101929. doi: 10.1016/j.epsc.2021.101929.

Epub 2021 Jun 2.

7- Hatakeyama T, Okata Y, Miyauchi H, et al: Colonic diverticulitis in

children: A retrospective study of 16 patients. Pediatr Int.

63(12):1510-1513, 2021

Inguinal Lymphadenopathy

Inguinal lymphadenopathy (IL) refers to the condition in

which peripheral inguinal or groin lymph nodes become abnormally

enlarged, sometimes tender to palpation causing concern to caretakers.

Lymphadenopathy is a common clinical manifestation in the pediatric age

group. It may be part of normal age-related physiology or in response

to any local or generalized infection in the body. Inguinal

adenopathy may be a symptom to several disease process, most commonly

of infectious origin. The history of the child with IL should be

studied carefully since it provides clues to the underlying disease.

Most groin adenopathies are self-limited infections in young patients.

When confronted with a child with IL laboratory tests, imaging studies

and tissue diagnosis might be needed unless there is a clear

explanation for the sudden growth of the lymph node. Ultrasound, a

non-invasive and non-radiating imaging study, is the best study to

assess lymph nodes in the groin and neck. CT-Scan should be avoided

with peripheral lymphadenopathies to reduce radiation injury associated

with this imaging modality. CT-Scan is more helpful with central lymph

nodes in the thorax or abdominopelvic cavities. Fine needle aspiration

(FNA) biopsy can be used as initial management. FNA biopsy is

easy, safe, rapid and a cost-effective tool, but will need a

cooperating child to be performed. Excisional biopsy of the enlarged

lymph node is the gold standard procedure and in the groin the

procedure is usually simple, fast, and free from major complications.

In fact, the most common complication is seroma which resolves

spontaneously in most cases. In the groin lymph nodes larger than 1.5

cm in children are abnormal. It must be determined if the

lymphadenopathy is localized or generalized. Generalized

lymphadenopathy is defined as the enlargement of two or more groups of

noncontinuous groups of lymph nodes. It results from systemic illness

like infections (viral, bacterial, fungal, and protozoan),

malignancies, autoimmune disease, drugs reactions, histiocytic

disorders, disseminated neoplastic diseases and storage disorders. If

the child does not present with overt signs of malignancy, the lymph

node can be safely watch for three to four weeks before considering

biopsy. Benign lesions are more commonly encountered than malignant

lesions in children and include benign reactive hyperplasia (by far the

most common pathology; approximately 65-85%), chronic skin diseases,

cat-scratch disease, toxoplasmosis, necrotizing granulomatosis, and

non-necrotizing granulomatosis. Of the malignant conditions,

non-Hodgkin lymphoma is the most common. FNA biopsy can be helpful in

differentiating benign from malignant pathology but is often faced with

failure due to quantity of tissue to provide a diagnosis. As mentioned

previously, an open biopsy with removal of the whole adenopathy is

almost always diagnostic. Chronic skin disorders are a cause of what is

known as dermatopathic lymphadenopathy, an entity that represents a

secondary immune response to a pathologic condition affecting primarily

the skin.

References:

1- Ozkan EA, Goret CC, Ozdemir ZT, et al: Evaluation of peripheral

lymphadenopathy with excisional biopsy: six-year experience. Int J Clin

Exp Pathol. 8(11):15234-9, 2015

2- Garces S, Yin CC, Miranda RN, et al: Clinical, histopathologic, and

immunoarchitectural features of dermatopathic lymphadenopathy: an

update. Mod Pathol. 33(6):1104-1121, 2020

3- Khatri A, Mahajan N, Malik S, Rastogi K, Kumar P, Saikia D:

Peripheral Lymphadenopathy in Children: Cytomorphological Spectrum and

Interesting Diagnoses. Turk Patoloji Derg. 37(3):219-225, 2021

4- Sandoval AC, Reyes FT, Prado MA, Pena AL, Viviani TN: Cat-scratch

Disease in the Pediatric Population: 6 Years of Evaluation and

Follow-up in a Public Hospital in Chile. Pediatr Infect Dis J.

39(10):889-893, 2020

5- Abantanga FA: Groin and scrotal swellings in children aged 5 years and below: a review of 535

cases. Pediatr Surg Int. 19(6):446-50, 2003

6- Hasanbegovic E, Mehadzic S: [Etiology of lymphadenopathy in childhood]. Med Glas (Zenica). 7(2):132-6, 2010

PSU Volume 58 NO 04 APRIL 2022

Brunner Gland Adenoma

Brunner gland adenoma (BGA), also known as an hamartoma, is

a rare duodenal lesion comprising not more than 5% of benign duodenal

lesions. Most Brunner gland adenomas are of small size without causing

significant symptoms. When BGA grows, they can cause obstruction or

bleeding. Brunner glands are submucosal mucin-secreting glands

predominantly located in the posterior wall of the duodenal bulb and

second portion of the duodenum segment and progressively decrease in

size and number in the distal potions of the proximal bowel. Brunner's

glands secrete an alkaline fluid composed of viscous mucin which

protects the duodenal epithelium from acid chyme of the stomach. BGA

are rarely larger than 2 cm in asymptomatic individuals, while larger

than 5 cm in symptomatic patients. Brunner's gland could be classified

into three types based on size: type 1 (diffuse nodular hyperplasia)

confined to the mucosa with multiple sessile projections occupying most

of the duodenum; type 2 (circumscript nodular hyperplasia), found in

the bulb duodenum and usually smaller than 1 cm; and type 3 (Brunner's

gland adenoma) stemmed with sized 1-2 cm, generally without clinical

manifestations. Etiology of BGA is unknown. It is believed that gastric

hypersecretion of acid results in hyperplasia of Brunner's gland

resulting in adenoma formation and excrescence toward the bowel lumen.

Others believe the loss of the alkaline protection of the exocrine

pancreas leads to compensatory hyperplasia of Brunner's gland with

increased production of mucus and alkali. Helicobacter infection has

also been found culprit of BGA, though a clear relationship has not

been met. It is believed BGA are hamartomas. The word adenoma might be

a misnomer, since the mass is not a true neoplasm, but rather a

hamartomatous or hyperplastic collection of mature glands with no known

potential for malignant transformation. Patients with BGA are usually

asymptomatic, or developed symptoms of nausea, vomiting, bloating,

dyspepsia, vague abdominal pain, melena, or hematemesis. Pancreatitis

(ampullary lesions), intussusception and diarrhea have also been

reported. Those in the pylorus often presents with epigastric pain,

dyspnea, or melena, whereas those in the posterior wall of duodenum

often presents with postprandial fullness. When the adenoma grows it

can cause symptoms of obstruction or gastrointestinal bleeding. Chronic

bleeding with ulceration is found in most symptomatic patients.

On rare occasion BGA can cause gastric outlet obstruction. The most

common laboratory finding in symptomatic patients is anemia. Abdominal

imaging (Ultrasound/CT-Scan/MRI) or endoscopy can detect the lesion.

Upper endoscopy localizes the lesion and biopsy can provide the

diagnosis of a BGA. Endoscopic biopsy shows involvement of the mucosa

and submucosa layers without deeper extension, variable echogenicity,

and cystic changes within the lesion. Cytologically, Brunner's gland

shows loose clusters of flat, two-dimensional cells with minimal

overlapping or atypia showing abundant, finely granular, and vacuolated

cytoplasm. In most cases, diagnosis is confirmed after endoscopic or

surgical resection. Endoscopic resection is recommended to avoid

developing symptoms with time. When endoscopic resection is not

possible, surgical resection is indicated. Recurrence rate after both

modalities of management is very low. BGA have been reported very

rarely in the pediatric age and can be associated with surgical repair

of duodenal atresia. BGA are benign and the prognosis after endoscopic

or surgical management is good.

References:

1- Lu L, Li R, Zhang G, Zhao Z, Fu W, Li W: Brunner's gland adenoma of

duodenum: report of two cases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 8(6):7565-9, 2015

2- Marinacci LX, Manian FA: Brunner Gland Adenoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 92(11):1737-1738, 2017

3- Ortiz Requena D, Rojas C, Garcia-Buitrago M: Cytological diagnosis

of Brunner's gland adenoma (hyperplasia): A diagnostic challenge. Diagn

Cytopathol. 49(6):E222-E225, 2020

4- Liang M, Liwen Z, Jianguo S, Juan D, Ting S, Jianping C: A case

report of endoscopic resection for the treatment of duodenal Brunner's

gland adenoma with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Medicine

(Baltimore). 99(52):e23047, 2020

5- Yang B, Li K, Luo R, Xiong Z, Wang L, Xu J, Fang D: Large Brunner's

gland adenoma of the duodenum for almost 10 years. Open Life Sci.

15(1):237-240, 2020

6- Zhou SR, Ullah S, Liu YY, Liu BR: Brunner's gland adenoma: Lessons learned for 48 cases. Dig Liver Dis. 53(1):134-136, 2021

Hirschsprung's Associated Enterocolitis (HAEC)

Hirschsprung's disease (HD) occurs in approximately one in

5000 live births with most babies presenting with failure to pass

meconium in the first 24 hours of life. Failure to recognize HD early

in infancy place them at high risk of developing HirschsprungÕs

associated enterocolitis (HAEC). HAEC is a serious life-threatening

inflammatory complication of HD. HAEC occurs preoperatively in 6-26% of

cases, and post pull-through surgery in 5-42%. HAEC is histologically

characterized by cryptitis, the appearance of neutrophils in intestinal

crypts. They progress to crypt abscess, mucosal ulceration and

fibrinopurulent debris. In severe cases ischemia, transmural necrosis

and perforation can occur leading to shock and hypoperfusion.

Pathophysiologic mechanism associated with HAEC includes partial

mechanical obstruction (bacterial translocation), unbalanced microflora

(dysbiosis), insufficient immunoglobulin secretion, abnormal mucin

production (impaired mucosal barrier), and dysfunction of the enteric

nervous system. Mortality of HAEC ranges between 1% and 10%. Several

factors contribute to an increased risk of HAEC, these include family

history of HD, Down syndrome, long-segment HD involvement, obstruction

from any cause (retained aganglionosis, transitional zone pull-through,

dysmotility following pull-through, anastomotic stricture, twist in the

pull-through or tight muscular cuff following surgery), and prior

episodes of HAEC. Some authors believe no patient or clinical

characteristic is associated with the risk of postoperative HAEC. The

risk of developing HAEC increases with the length of the aganglionic

segment and delay in diagnosis. The diagnosis is suspected when a child

with constipation develops abdominal distension, pain, vomiting,

explosive watery diarrhea, fever, lethargy, rectal bleeding, and shock.

Initial images consist of plain radiographs which can demonstrate a

cutoff sign in the rectosigmoid colon with absent distal air, dilated

proximal bowel loops, air fluid levels, pneumatosis intestinalis,

"sawtooth' appearance with irregular intestinal lining, or

pneumoperitoneum from bowel perforation. Barium enema and colonoscopy

are contraindicated in the acute setting due to the risk of

perforation, while CT-Scans are of little value in the diagnosis and

treatment of HAEC. Chronic HAEC symptoms include persistent diarrhea,

soiling, intermittent abdominal distension, and failure to thrive.

Should this occur after surgical management mechanical obstruction from

aganglionosis should be suspected and confirmed with rectal biopsy. The

diagnosis of HD is made histologically by the absence of ganglion

cells, presence of nerve hypertrophy and absent calretinin

immunohistochemistry. For prophylactic prevention of HAEC routine

rectal irrigation or diverting colostomy is indicated in selected

patients. Rectal irrigations reduce fecal stasis and bacterial load,

limiting colon distension. Children with HD and severe congenital heart

disease should be diverted to avoid HAEC. Probiotics management has

controversial results as a preventive measure. The clinical suspicion

and severity of HAEC have been graded based on history, physical

examination, imaging studies and laboratory findings similar to Bell's

criteria for neonatal enterocolitis. Four or more of 16 criteria seen

in the Table below are diagnostic. Such score helps make the correct

diagnosis of HAEC. Existing scoring systems perform poorly in

identifying episodes of HAEC, resulting in significant underdiagnosis.

Management of HAEC includes fluid resuscitation using isotonic

solutions, broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics, decompression of the

gastrointestinal tract and bowel rest. Systemic antibiotics are used

empirically in HAEC, with metronidazole typically chosen to managed

anaerobes. Those children with severe sepsis and acutely ill (Grade

III) benefit with admission to the intensive care unit some of them

needing vasopressor therapy and ventilatory support. Rectal washouts

with warm saline are the mainstem of management and they should be

performed two to four times daily at a rate of 10-20 ml/kg of weight

each time or until the effluent is clear. In newborns presenting with

severe HAEC, shock and sepsis immediate diversion (leveling colostomy)

should be considered. Other risk factor associated with the need of

diversion includes delayed presentation, co-morbid conditions, presence

of HAEC or multiple risk factors for HAEC in the preoperative period.

Diversion improves patient symptoms but does not resolve HAEC

development later in life. HAEC can also occur in the postoperative

period after pull-through definitive surgery. Rectal washouts are also

effective to manage postoperative HAEC. There is a trend toward a

higher incidence of enterocolitis in the primary endorectal

pull-through group as compared with those with a two-stage approach.

Postoperative HAEC can occur more than 18 months after definitive

surgery. The postoperative risk of developing HAEC after

definitive surgery is highest in those operated with Swenson and

Duhamel approach (20%), and lowest with Soave procedure (11%). Children

with recurrent HAEC, occurring in 2-33% of patients, should be

evaluated for anatomic or pathologic causes of obstruction. A

water-soluble contrast enema can identify any mechanical cause of

obstruction. Should the suspicion of persistent aganglionosis be

considered a rectal biopsy should be performed. Risk factors for

recurrent HAEC includes preoperative HAEC, history of central nervous

system infection and congenital chromosome anomalies and does not

include placement of an ostomy prior to pull-through and congenital

cardiac anomalies. Recurrent postoperative HAEC does not have an impact

on mortality. Children with previous episodes of HAEC are more likely

to develop subsequent episodes.

References:

1- Frykman PK, Short SS: Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis: prevention and therapy. Semin Pediatr Surg. 21(4):328-35, 2012

2- Demehri FR, Halaweish IF, Coran AG, Teitelbaum DH:

Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis: pathogenesis, treatment and

prevention. Pediatr Surg Int. 29(9):873-81, 2013

3- Gosain A, Frykman PK, Cowles RA, et al: Guidelines for the diagnosis

and management of Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis. Pediatr Surg

Int. 33(5):517-521, 2017

4- Frykman PK, Kim S, Wester T, et al: Critical evaluation of the

Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis (HAEC) score: A multicenter study

of 116 children with Hirschsprung disease. J Pediatr Surg.

53(4):708-717, 2018

5- Pruitt LCC, Skarda DE, Rollins MD, Bucher BT:

Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis in children treated at US

children's hospitals. J Pediatr Surg. 55(3):535-540, 2020

6- Roorda D, Oosterlaan J, van Heurn E, Derikx JPM: Risk factors for

enterocolitis in patients with Hirschsprung disease: A retrospective

observational study. J Pediatr Surg. 56(10):1791-1798, 2021

7- Lewit RA, Veras LV, Cowles RA, et al: Reducing Underdiagnosis of

Hirschsprung-Associated Enterocolitis: A Novel Scoring System. J Surg

Res. 261:253-260, 2021

8- Hagens J, Reinshagen K, Tomuschat C: Prevalence of

Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis in patients with Hirschsprung

disease. Pediatr Surg Int. 38(1):3-24, 2022

Transanal Pull-Through

In 1998, De la Torre introduced a new one-stage surgical

technique to manage Hirschsprung's disease (HD) where rectal

mucosectomy, aganglionic segment colectomy, posterior myectomy, and

normoganglionic colon pull-through is performed through the anus. HD

aganglionosis affects the rectosigmoid (classic HD; 85%), long-segment

(10%) and total aganglionosis (5%) of the colon with sporadic cases

affecting the proximal small bowel. The transanal pull-through (TAPT)

is mainly design for children with classic HD and uses a prone

approach, though it can also be performed in supine position.

Advantages of the TAPT include abdominal or intraperitoneal bowel

opening is not necessary unless the child has a previous leveling

colostomy, risk of adhesion is decreased, excellent cosmetic results,

earlier full oral feedings, shorter hospital stay, less costs, less

pain, reduced operating time, endorectal dissection preserves the

anorectal sphincters and their blood supply along with innervation

causing less damage to fecal and urinary incontinence. Should the

ganglionic bowel need further dissection proximally laparoscopy can

provide this mobilization. The procedure can be performed in newborns

with potential benefits of avoiding a colostomy and establishing

colonic continuity early in life improving continence results. A stoma

in HD is considered appropriate in children with bowel perforation

(usually cecal), severe malnutrition, severe enterocolitis, very

dilated proximal bowel, total colonic aganglionosis or lack of adequate

pathological support. Should the surgeon choose to wait beyond the

neonatal period for final correction of HD the risk of developing

enterocolitis should be minimized by ensuring adequate decompression of

the proximal dilated bowel by appropriate daily irrigations,

administration of prophylactic metronidazole or probiotics, and use of

breast feeding or elemental infant formula. Using laparoscopy

concomitantly with the transanal approach can help in the proximal

bowel dissection, distal bowel dissection and obtaining a seromuscular

biopsy for frozen section to determine the ganglionic bowel to be

pull-through. A frozen full-thickness biopsy helps the pathologist see

both submucosa and myenteric plexus in look for ganglion cell and nerve

hypertrophy minimizing error. Whether using a supine or prone position

for the procedure depends on the certainty that you are dealing with

classic HD and proximal mobilization will not be required. The prone

position has the advantage that mesenteric vessels can be send and

controlled more effectively than in the supine or lithotomy position.

The transanal dissection can be started 0.5-1 cm above dentate line in

neonates and 1-2 cm above the dentate line in older children as the

transitional epithelium must not be damaged to avoid loss of sensation

and incontinence. Dissection on the outside of the rectum, as that used

during laparoscopic or open Swenson procedures, may increase the risk

of injury to pelvic nerves and vessels, and to the prostate, urethra,

and vagina. Comparison between complete TAPT and laparoscopic-assisted

TAPT do not differ between rates of major complications, including

leaks, strictures, enterocolitis, fecal incontinence, postoperative

obstructive symptoms, and mean length of stay. Comparison between the

Duhamel procedure and the TAPT have shown they are similar in respect

postoperative fecal incontinence and operation time, but the Duhamel is

associated with longer hospital stay and lower rate of enterocolitis.

When performing the TAPT in neonates, a higher incidence of

enterocolitis has been reported due to increased risk of sphincter

spasm and anastomotic strictures. Excising the entire posterior rectal

muscle cuff (myectomy) has been effective in reducing the incidence of

enterocolitis. Current guidelines suggest doing the TAPT between two

and three months of age if the child is growing well and the bowel is

sufficiently decompressed. Whether performing the procedure totally

transanally or laparoscopy assisted does not affect long-term bowel

function. More than 20% of patients develop at least one complication

within the 30-days following a TAPT. Older age at time of surgery

increases the risk of developing a postoperative complication. They

include anastomotic leakage, abdominal abscess, and anastomotic

strictures. Ischemia and increased tension on the colon anastomosis

play an important role in leakage and stricture. This is one reason to

consider perioperative diverting stoma in older patients. Older age at

time of surgery, laparotomy-assisted and long segment disease increases

the risk of developing a postoperative complication. Long term problems

with pull-through surgery for HD include obstructive symptoms (30%),

persistent constipation, soiling, enterocolitis and descending

aganglionic bowel. Persistent bowel obstructive problems might be

caused by mechanical obstruction, recurrent or acquired aganglionosis,

disordered motility in the proximal colon, nonrelaxation of the

internal anal sphincter, or stool-holding behavior. Mechanical

obstruction might also be caused by an anastomotic stricture, twisted

descended pull-through colon, or rolling of a long muscular cuff left

behind. They are managed by sequential dilatations or redo pull-though

surgery. Soiling can be caused by damage sphincter function

(incontinence), abnormal sensation and pseudo-incontinence. Anorectal

manometry is indicated to determine the cause. Soiling not associated

with constipation is caused by true fecal incontinence and does not

improve with time. Thus, to preserve the anal canal and avoid sphincter

damage are of vital importance during the TAPT. Enterocolitis is

managed with bowel rest, colonic irrigations, and systemic antibiotics.

Most children have an excellent quality of life going into adulthood

after TAPT. Besides the management of HD, the TAPT can be utilized for

children born with rectal atresia, for severe chronic idiopathic

constipation associated with megarectosigmoid, idiopathic rectal

prolapse, and children with rectal prolapse after anorectal

malformation correction.

References:

1- De la Torre-Mondragon L, Ortega-Salgado JA: Transanal endorectal

pull-through for Hirschsprung's disease. J Pediatr Surg. 33(8):1283-6,

1998

2- De La Torre L, Langer JC: Transanal endorectal pull-through for Hirschsprung disease: technique,

controversies, pearls, pitfalls, and an organized approach to the

management of postoperative obstructive symptoms. Semin Pediatr Surg.

19(2):96-106, 2010

3- Langer JC: Laparoscopic and transanal pull-through for Hirschsprung disease. Semin Pediatr Surg. 21(4):283-90, 2012

4- Mao YZ, Tang ST, Li S: Duhamel operation vs. transanal endorectal pull-through procedure for

Hirschsprung disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 53(9):1710-1715, 2018

5- Miyano G, Takeda M, Koga H, et al: Hirschsprung's disease in the

laparoscopic transanal pull-through era: implications of age at surgery

and technical aspects. Pediatr Surg Int. 34(2):183-188, 2018

6- Fosby MV, Stensrud KJ, Bjornland K: Bowel function after transanal

endorectal pull-through for Hirschsprung's disease - does outcome

improve with time?. J Pediatr Surg 55: 2375, 2378, 2020

7- Beltman L, Roorda D, Backes M, Oosterlaan J, van Heurn LWE, Derikx

JPM: Risk factors for short-term complications graded by Clavien-Dindo

after transanal endorectal pull-through in patients with Hirschsprung

disease. J Pediatr Surg. 2021 Aug 1:S0022-3468(21)00533-9. doi:

10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2021.07.024.

8- Karlsen RA, Hoel AT, Fosby MV, et al: Comparison of clinical

outcomes after total transanal and laparoscopic assisted endorectal

pull-through in patients with rectosigmoid Hirschsprung disease.

J Pediatr Surg. 2022 Jan 15:S0022-3468(22)00046-X. doi: 10.1016

PSU Volume 58 NO 05 MAY 2022

Slipping Rib Syndrome

Slipping rib syndrome (SRS) is a rare cause of lower rib and

abdominal pain in children and adults. SRS accounts for approximately

5% of all musculoskeletal chest pain in primary care. SRS is caused by

a hypermobility of the anterior false ribs that allows the 8th to 10th

ribs to slip or click as the cartilaginous rib tip abuts under the rib

above. The costal cartilage slips out of its normal anatomical

position, the anterior false ribs (8th through 10th) slide out of

orientation and become pinned underneath their adjacent superior ribs.

This displacement is caused by a congenital anomaly, damage to the

fibrinous articulation, or hypermobility of unknown origin. Impingement

of the intercostal nerve along the adjacent surface of the adjacent

ribs during this slip occurs causing acute pain. Failure to diagnose

this condition might lead to unnecessary tests in the child. The pain

is caused when the lower costal cartilages 8th to 10th which are not

connected to the sternum lose their fibrous or cartilaginous

attachments to each other. Pain can extend to the floating ribs (11th

and 12th). Movements in the child such as twisting, simple lumbar

flexion, bending, deep breathing, laughing, sitting, sneezing, or

coughing results in irritation of the intercostal nerve hence pain.

Pain is sharp, intermittent, stabbing lasting for a few minutes

followed by a dull or burning sensation for several hours. Sometimes

associated with nausea and vomiting. Slippage may produce a clicking or

popping sensation. Pain can range anywhere from the midline to the

lateral flank and from the xiphoid process to as inferiorly as the

umbilical line. Due to interconnections between intercostal and somatic

visceral nerves the pain might be interpreted as upper abdominal

(subcostal). The lack of significant radiographic findings makes the

diagnosis of SRS difficult using imaging. Time to diagnosis is often

years. Differential diagnosis includes rib fracture, chondritis and

pleuritic pain. There is usually one dominant affected side, though the

syndrome can occur bilaterally. SRS can occur in any age group and

females athletes (swimmers) are more commonly affected than males. Many

of these patients have hypermobile joints with laxity and subluxation

without symptoms. Diagnosis is established through history and physical

examination as imaging are not very useful. Dynamic US can be of help

in the diagnosis by demonstrating an overlapping movement of the lower

rib above the upper rib. Less thickness of the ipsilateral rectus

abdominis muscle has also been found. Pain is intermittent and

localized to the lower ribcage with some trigger point of tenderness

palpable. Popping or grinding sensation with movement can be elicited.

At physical exam the hook maneuver, the examiner slides his finger

under the costal margin and lift anteriorly and superiorly, reproducing

a click and pain and diagnosing the condition. Careful palpation can

identify the disconnected cartilage, or the cartilage curling beneath

the overlying ribcage causing point tenderness. Compressing on the

sides of the ribs simultaneously may reproduce the pain at the affected

costal margin. As a temporary and localizing measure, a local

anesthetic rib block with Bupivacaine can be performed which provides

temporary or complete symptoms relief. Repeated anesthetics and steroid

rib block, manipulative techniques, acupuncture, Botox injections,

prolotherapy, and topical anesthetics produce long-lasting results.

Should conservative measures fail, the management should consist of

removing the slipping, disconnected cartilages through a small incision

at the affected lower subcostal margin. The hypermobile cartilage is

removed all the way to the costochondral junction in most cases

including the perichondrium to avoid regrowth of the cartilage. During

this maneuver, the intercostal neurovascular bundle is preserved.

Injury to the neurovascular bundle can cause acute blood loss or

chronic neuropathic pain. The use of a vertical bioabsorbable plate to

stabilize the hyperflexible subluxing bony ribs used to stabilize

fractures is also highly recommended to be incorporated with resection

of the cartilages as recurrence rate are decreased significantly. If

the patient develops recurrent symptoms after surgery, this might be

due to missed slipping cartilages during the initial procedure,

regrowth of the cartilage, or new symptoms on the contralateral side.

Most patients are satisfied after surgical resection of the slipping

ribs.

References:

1- McMahon LE: Slipping Rib Syndrome: A review of evaluation, diagnosis and treatment. Semin Pediatr Surg. 27(3):183-188, 2018

2- Gress K, Charipova K, Kassem H, et al: A Comprehensive Review of

Slipping Rib Syndrome: Treatment and Management. Psychopharmacol Bull.

50(4 Suppl 1):189-196, 2020

3- Fraser JA, Briggs KB, Svetanoff WJ, St. Peter SD: Long-term outcomes

and satisfaction rates after costal cartilage resection for slipping

rib syndrome. J Pediatr Surg 56: 2258-2262, 2021

4- Foley Davelaar CM: A Cinical Review of Slipping Rib Syndrome. Curr Sports Med Rep. 20(3):164-168, 2021

5- McMahon LE, Salevitz NA, Notrica DM: Vertical rib plating for the

treatment of slipping rib syndrome. J Pediatr Surg. 56(10):1852-1856,

2021

6- Romano R, Gavezzoli D, Gallazzi MS, Benvenuti MR: A new sign of the

slipping rib syndrome? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 34(2):331-332,

2022

Encapsulating Peritoneal Sclerosis

Peritoneal dialysis is the preferred chronic dialysis modality in

the pediatric age. Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis (EPS) is a rare

but most serious complications of continuous ambulatory peritoneal

dialysis (CAPD) in end-stage renal patients. The incidence of EPS in

children receiving CAPD is 2-15% depending on the long-term use of

CAPD, while the mortality exceeds 30% with most survivors requiring

long-term parenteral nutrition. EPS is characterized by progressive

fibrosis of the peritoneum resulting in reduced ultrafiltration

capacity, dysfunctional peristalsis of the bowel, and partial or

complete bowel luminal obstruction. EPS involves both the visceral and

parietal peritoneum. EPS is not specific to CAPD children and can be

seen secondary to drug therapy (Beta-blockers), sarcoidosis, systemic

lupus erythematosus, abdominal tuberculosis, gastrointestinal

malignancies, protein S deficiency and ovarian luteinized thecomas. EPS

is a clinical syndrome that continuously, intermittently, or repeatedly

presents with symptoms of intestinal obstruction due to adhesions of

diffusely thickened peritoneum. The diagnosis of EPS is based on

clinical, histologic, and radiographic findings. The pathophysiological

event in the development of EPS is an inflammatory process resulting in

loss of the mesothelial layer of the peritoneum and fibroconnective

tissue proliferation. Fibrin deposition and fibrinolysis with

hyalinization of the superficial stromal collagen possibly tanned

through nonenzymatic glycosylation by the dialysate glucose plays an

important role in causing excessive fibrogenesis in children with CAPD.

Contributing events include duration of CAPD (single most significant

risk factor), recurrent episodes of bacterial or fungal peritonitis,

the acetate dialysis solution, chlorhexidine, plasticizers, and

cumulative exposure to hypertonic glucose-based dialysis solutions. The

rate of developing EPS increases with the years receiving CAPD. If a

child receives CAPD for more than five years and shows poor

ultrafiltration with peritoneal calcifications on CT-Scan, a peritoneal

biopsy should be performed to rule out the presence of severe EPS.

Peritoneal biopsies of EPS show loss of normal mesothelial cells,

massive expansion of the submesothelial compact zone and increased

vascularization, mononuclear cell infiltration, calcifications, and low

peritoneal mast cell number. EPS occurs insidiously with vague

presenting symptoms initially. Symptoms of EPS include weight loss,

malnutrition, low-grade fever, nausea, vomiting, hemorrhagic effluent,

ultrafiltration failure, ascites, and recurrent bouts of abdominal pain

to subacute or acute intestinal obstruction with bowel necrosis.

Imaging might show dilated small bowel loops, air-fluid levels, and

calcific plaques. Ultrasound is the most sensitive modality to detect

EPS demonstrating thickened bowel wall with a trilaminar appearance and

adhesion of bowel loops to the anterior abdominal wall. CT-Scan

demonstrates peritoneal thickened, bowel teetering, thickened bowel

wall, loculated ascites, peritoneal calcification, and clouding of

mesenteric fat. The cocoon appearance is secondary to the presence of a

thick fibrous layer encapsulating the small bowel. Some recommendations

to stop peritoneal dialysis in cases with EPS include ultrafiltration

failure, bloody deacylate with calcifications of the peritoneum,

duration longer than eight years of dialysis, persistency elevated

C-reactive protein and recurrent peritonitis. EPS can occur up to five

years after withdrawal of CAPD, when on hemodialysis, or after

transplanted. These cases are all characterized by an acute

presentation with a rapid clinical course. Management of EPS includes

termination of peritoneal dialysis, immunosuppression, steroids

(anti-inflammatory), tamoxifen (antifibrotic agent), and surgical

debridement. Surgical therapy is required when the child does not

respond to medical therapy or presents with complete bowel obstruction,

bowel perforation or hemoperitoneum. Total enterolysis and Noble

plication are the methods suggested in the literature. Preventing EPS

includes minimizing dialysate glucose exposure, preventing acute

peritoneal dialysis peritonitis and using a neutral-pH solution.

References:

1- Honda M, Warady BA: Long-term peritoneal dialysis and encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in

children. Pediatr Nephrol. 25(1):75-81, 2010

2- Debska-Slizien A, Konopa J, Januszgo-Giergielewicz B, et al:

Posttransplant encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis: presentation of

cases and review of the literature. J Nephrol. 26(5):906-11, 2013

3- Stefanidis CJ, Shroff R: Encapsulating peritoneal sclerosis in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 29(11):2093-103, 2014

4- Brown EA, Bargman J, van Biesen W, et al: Length of Time on

Peritoneal Dialysis and Encapsulating Peritoneal Sclerosis - Position

Paper for ISPD: 2017 Update. Perit Dial Int. 37(4):362-374, 2017

5- Jagirdar RM, Bozikas A, Zarogiannis SG, Bartosova M, Schmitt CP,

Liakopoulos V: Encapsulating Peritoneal Sclerosis: Pathophysiology and

Current Treatment Options. Int J Mol Sci. 20(22):5765, 2019

6- Sharma V, Moinuddin Z, Summers A, et al: Surgical management of

Encapsulating Peritoneal Sclerosis (EPS) in children: international

case series and literature review. Pediatr Nephrol. 2021 Aug 26. doi:

10.1007/s00467-021-05243-0.

7- Keese D, Schmedding A, Saalabian K, Lakshin G, Fiegel H, Rolle U:

Abdominal cocoon in children: A case report and review of literature.

World J Gastroenterol. 27(37):6332-6344, 2021

Burnout Syndrome

Burnout syndrome is a psychological syndrome arising from the

continued response to chronic interpersonal stressors while at work.

Defined as a state of physical and mental exhaustion related to

caregiving activities or work is a severe problem affecting medical

personal and healthcare organizations. Emotional exhaustion and

irritability in the work environment leads to development of

psychiatric problems characterized by emotional exhaustion,

depersonalization, and diminished personal accomplishment. The three

main components of burnout are overwhelming exhaustion, feeling of

cynicism or depersonalization, and a sense of ineffectiveness and lower

efficacy. Burnout is the most common mental issue faced by residents